I recently had the opportunity to interview Matthias Kaiser, a professor at Bergen University and, at the time of the interview, Director of the Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities. He is part of an expert team that has given scientific advice to Norwegian policymakers, highlighting the issues that should be considered when dealing with the U-864 submarine wreckage and its cargo, 67 tonnes of mercury.

Firstly, can you tell us a bit about the history of the submarine – why was it was carrying so much mercury in the first place?

It was during the late phase of World War II, the Nazis believed that the Japanese were at risk of losing and decided to help them by sending over materials for weapon production. One particular submarine that they sent from Europe to Japan had a load of 67 tonnes of mercury.

Map of Fedje where the sunken U-864 submarine is located. Map created December 7 2006, by ‘NormanEinstein’.

When the submarine left Norway, it was hit by a torpedo from an English submarine and sunk immediately down to the continental shelf [to a depth of 150m] just outside of Bergen, in a place called Fedje. The submarine was located in the early 2000s and after negotiations between Germany and Norway, Norway decided that they would take possession and organise what to do with it. Since then, discussions have started regarding what should be done with the submarine and particularly, what should be done with the mercury on it. To lift it up, out of the water or to cover it up – with basically mud and stones.

What did the Parliament decide and what information did they base their decision on?

There has been a little bit of a public debate and there has been, as there is very often is, conflicting scientific views in the newspapers. There was also an official assessment undertaken by the [Norwegian Coastal Administration] at the request of the Ministry which, again, acts on behalf of the Norwegian Parliament (Stortinget). They recommended that the submarine be covered up. One of the reasons for this was that their risk assessment showed there was no strong risk associated with it. And the other reason for the decision was that that it would only cost a third of the money compared to the alternative.

For many reasons, it took a long time to get through the bureaucratic processes and then there was some assessment made on how it could be covered up. Last year, the Parliament put it into their budget. At that point, the coastal community (Fedje) contacted us at Bergen University and asked for help because they said “What has been done here is not good”.

So, we formed an expert team of three people. One chemist, one environmental toxicologist and me, because I have done something on risk assessment and worked on the precautionary principle. We went to the Parliament – first, to the group from the western coast of Norway, and we said,

“Hey folks, you’re about to make some decisions on this, but we want to tell you that the scientific basis that has been presented to you is insufficient” and we gave them some of our reasons and worries.

This led to another hearing in parliament with a larger committee. They were also convinced and sent a message back to the ministry saying, “Hey! Take that out of the budget and do a new assessment”.

Then, we had a meeting with the minister and the ministry which was problematic because they wanted to be finished with it after so many years. We recommended an independent study but they didn’t quite follow-up on it, instead giving it back to the Coastal Administration who then had a competition, a call, for consultants to come up with new information about technical possibilities – this all had to be done within 5-6 weeks.

Later, we met with the consultancy who was selected. They came back with a report saying that yes, the initial assessment was incomplete but they wouldn’t be able to do it better in such a short period of time. Otherwise, they said that they didn’t know much more except that the possibility of [removing the submarine] is much easier than previously thought.

We also had a meeting with a company who do such things and they convinced us that it would be the same price [as burying the submarine] and that there’s virtually no risk.

Right now, we are still in the process. An Op-Ed I wrote is about to be published and I will probably do a television interview. And after the summer, there’s going to be a new debate in Parliament.

Can you explain what the worst-case scenario would be?

The worst-case scenario would assumedly be if they cover [the submarine] up and that leads to a very quick leakage. There is potential for this to happen because there are torpedoes onboard the submarine which might be impacted by the coverup. That would affect all of the marine life, not only in this region but also in all of the North Atlantic, especially when it comes to the fish stocks. Because it’s a very sensitive area for some important fish stocks such as the cod, herring and mackerel. The ecology would be very much destroyed.

Secondly, it may have an impact on people’s health. The water would not be very safe anymore and it be a long-term effect. There was an event in Minamata, Japan that was tragic and actually involved less mercury. It led to the Minamata Convention on Mercury for which Norway was a signatory and said they would do everything possible to avoid this kind of leakage.

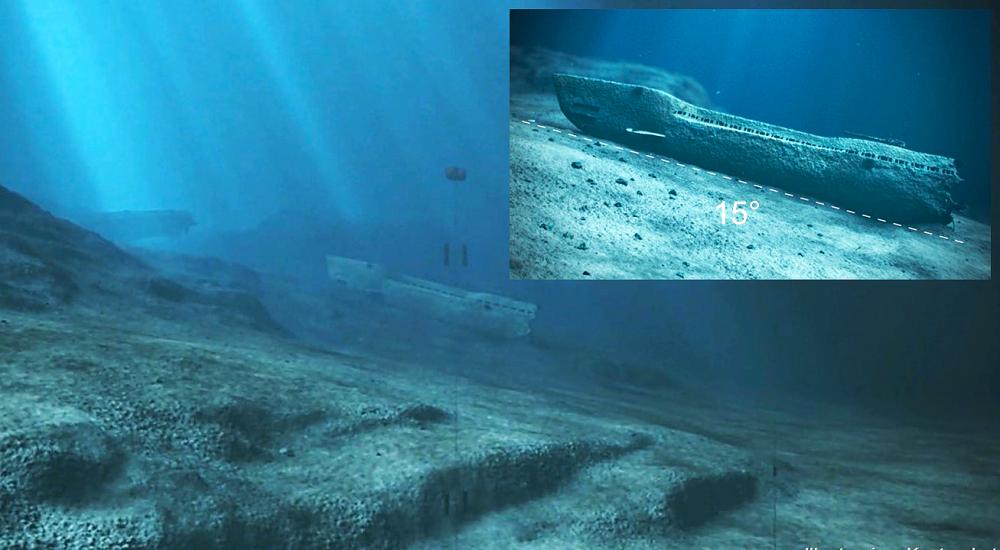

Illustration of U-864, showing the slope of the seabed where the wreckage is situated. Credit: Norwegian Coastal Administration

What do you think is going to happen?

I would like to be an optimist. In my life, I always hope that the better argument will survive and convince. On the other hand, looking back on my experience, I know that this is very often not the case. So, I don’t really know. Particularly, my hopes are with the Parliament, not with the administration so much. I think the Parliamentarians may be more open.

Final question, what is your advice to scientists who would like to engage with policy and who have never done it before?

The first thing that you need to do, and this is not only for natural scientists but all scientists who go into academia, is to improve your dialogical skills. Talk to people who disagree with you and who have very different views than you. This starts maybe at the University or maybe with your local community.

You can start this as a young scientist. For example, there will often be community hearings on environmental issues or construction plans – go and attend these meetings and try to ask intelligent questions.

Don’t talk down to people! Don’t talk as if you’re the only expert, because other people know other things. Listen, but present what you know. In that sense, start where you have the opportunity to make a difference. And on the local level, every student has, every young scholar has. And if that interests you, if you’re good at talking to people and people like to talking to you, aim higher!

A warm thank you to Matthias Kaiser for providing insights and sharing his experiences.