What is the land use and forestry regulation?

In October 2014, the EU agreed that all sectors, including land and forestry, should contribute to the EU’s 2030 climate & energy framework target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Almost 4 years later, in May 2018, the EU Commission’s proposal for the 2021-2030 land use and forestry regulation was adopted after being agreed upon by both the EU Parliament and the Council.

EU forests currently absorb the equivalent of almost 10% of the EU’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, the current rate of global land clearance amounts to approximately 24% of the world’s total emissions, more than the emissions from all forms of transport (including ships, planes and cars) in the world combined.

The land use and forestry regulation for 2021-2030 sets a binding commitment for each EU member state to ensure that greenhouse gas emissions from land use or land use change are offset by at least an equivalent removal of CO₂ from the atmosphere between 2021 and 31 December 2030. The “no debit rule” outlined in the 2021-2030 regulations requires EU countries to balance their deforestation with afforestation and / or boost CO₂ absorption by forests, croplands and grasslands where possible.

Although these binding commitments sound strict, EU member states could qualify for exemption in certain circumstances, such as large-scale wild fires. The EU has, however, stated that there will be clear rules and limits to these exceptions to ensure a loop-hole is not created. Member States will also be able to buy and sell net removals between each other which could potentially encourage some countries to reduce their CO₂ removals beyond their own commitment.

The 10-year regulation period will also be divided into five-year periods to increase member state flexibility. For example, if the average the net removals of CO₂ are higher than the net emissions from land use in the first five-year period (2021-2025), the emissions can be banked and used in the next period (2026-2030).

Apart from increasing afforestation rates and supporting land management that will help to reduce overall emissions, the regulation is expected to promote climate-smart agriculture practices, improve food production, protect biodiversity and encourage the development of a bio-based economy. Furthermore, biomass emissions used in energy generation (which until now were unaccounted for under EU law) will now be recorded and counted towards each member state’s 2030 climate commitments.

What role does science play in these regulations?

Scientific studies and research were used as the foundation for the land use and forestry regulation for 2021-2030 and will continue to be used to monitor the regulations success. The majority of the studies used to guide the regulation were conducted by EU agencies, such as the Joint Research Centre (JRC) and the European Environmental Agency (EEA). However, a vast quantity of external research was used to guide these studies as well as external experts and databases.

One of the primary studies used to guide the regulation presents statistical data on land cover and land use within the European Union (EU). The data were gathered as part of the land use/cover area frame survey (LUCAS) between March and October 2015. Having an understanding about how land is used within Europe allows a baseline for the 2021-2030 regulation to be set, the current rate of land use change to be estimated and the amount of emissions in a business as usual scenario to be predicted.

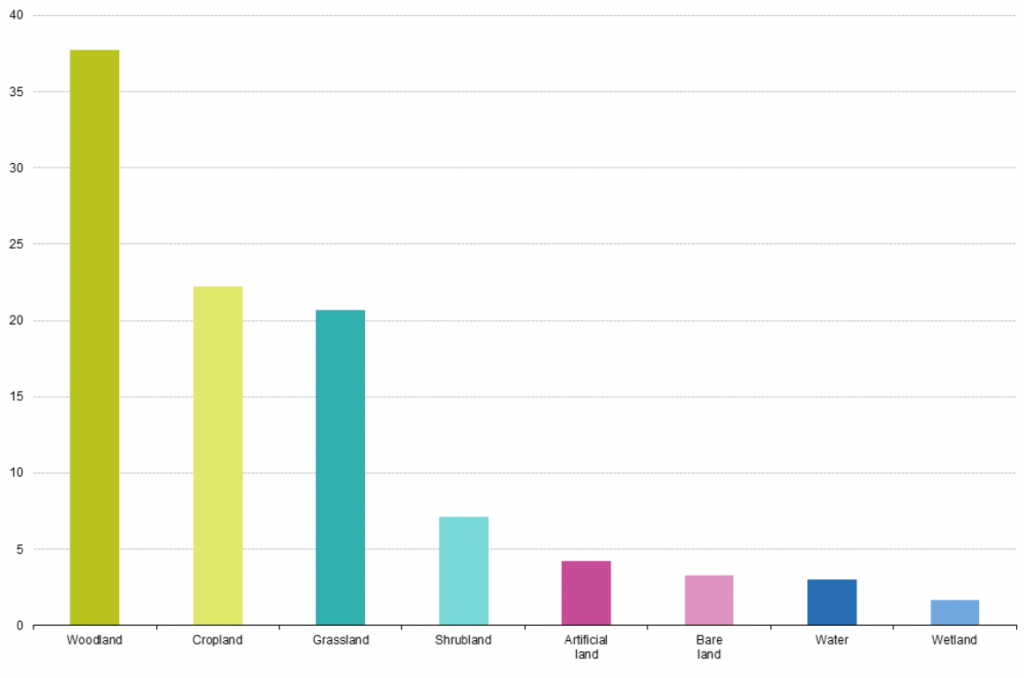

Figure 1: Main land cover by land cover type, EU-28, 2015. Source: Eurostat

Figure 1 shows the land cover type with forests and other wooded areas occupying more than one third of the EU. Cropland was the second most prevalent land type, covering 22% of the EU and artificial land (including all built-up areas, roads and railways) only amounts to 4.2% of all EU land. More information about the types of land cover in each EU country can be found here.

Another key study undertaken by the EEA outlined the drivers of land degradation, the influence of EU policies on land use and EU policy objectives. More indirectly, reports generated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), such as the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report of Working Group I, Summary for Policymakers, helped to steer the Paris Agreement and subsequent EU Climate policies.

Research will continue to play a large role in determining how member states adopt the regulations and how they are adapted over time. Formal evaluations allow for greater transparency and accountability in the public sector. They also ensure that the desired outcomes of the policy are being achieved and that any negative impacts of the policy are being minimised as much as possible. Evaluations may be conducted either prior to the adoption of policy, during their implementation and / or after the policy has come into effect. You can read more about the EU’s policy evaluation process here.

Further reading

donorcure

The forest reference levels should constrain the Member States’ ‘business as usual’ utilization of forest resources.