Although traditionally used to study earthquakes, like today’s M 8.1 in Mexico, seismometers have now become so sophisticated they are able to detect the slightest ground movements; whether they come from deep within the bowels of the planet or are triggered by events at the surface. But how, exactly, do earthquake scientists decipher the signals picked up by seismometers across the world? And more importantly, how do they know whether they are caused by an earthquake, nuclear test or a hurricane?

To find out we asked Neil Wilkins (a PhD student at the University of Bristol) and Stephen Hicks (a seismologist at the University of Southampton) to share some insights with our readers.

Seismometers are highly sensitive and they are able to detect a magnitude 5 earthquake occurring on the other side of the planet. Also, most seismic monitoring stations have sensors located within a couple of meters of the ground surface, so they can be fairly susceptible to vibrations at the surface. Seismologists can “spy” on any noise source, from cows moving in a nearby field to passing trucks and trains.

A nuclear test

On Sunday the 3rd of September, North Korea issued a statement announcing it had successfully tested an underground hydrogen bomb. The blast was confirmed by seismometers across the globe. The U.S. Geological Survey registered a 6.3 magnitude tremor, located at the Punggye-ri underground test site, in the northwest of the country. South Korea’s Meteorological Administration’s earthquake and volcano center also detected what is thought to be North Korea’s strongest test to date.

However they occur, explosions produce ground vibrations capable of being detected by seismic sensors. Mining and quarry blasts appear frequently at nearby seismic monitoring stations. In the case of nuclear explosions, the vibrations can be so large that the seismic waves they produce can be picked up all over the world, as in the case of this latest test.

It was realised quite early in the development of nuclear weapons that seismology could be used to detect such tests. In fact, the need to have reliable seismic data for monitoring underground nuclear explosions led in part to the development of the Worldwide Standardized Seismograph Network in the 1960s, the first of its kind.

Today, more than 150 seismic stations are operating as part of the International Monitoring System (IMS) to detect nuclear tests in breach of the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which opened for signatures in 1996. The IMS also incorporates other technologies, including infrasound, hydroacoustics and radionuclide monitoring.

The key to determining whether a seismic signal is from an explosion or an earthquake lies in the nature of the waves that are present. There are three kinds of seismic wave seismologists can detect. The fastest, called Primary (P) waves, cause ground vibrations in the same direction that they travel, similar to sound waves in the air. Secondary (S) waves cause shaking in a perpendicular direction. Both P and S waves travel deep through the Earth and are known collectively as body waves. In contrast, the third type of seismic waves are known as surface waves, because they are trapped close to the surface of the Earth. In an earthquake, it is normally surface waves that cause the most ground shaking.

In an explosion, most of the seismic energy is released outwards as the explosive material rapidly expands. This means that the largest signal in the seismogram comes as P waves. Explosions therefore have a distinctive shape in the seismic data when compared with an earthquake, where we expect S and surface waves to have higher amplitude.

Forensic seismologists can therefore make measurements of the seismic data to determine whether there was an explosion. An extra indication that a nuclear test occurred can also be revealed by measuring the depth of the source of the waves, as it would not be possible to place a nuclear device deeper than around 10 km below the surface.

Yet while seismic data can tell us that there has been an explosion, there is nothing that can directly identify that explosion as being nuclear. Instead, the IMS relies on the detection of radioactive gases that can leak from the test site for final confirmation of what kind of bomb was used.

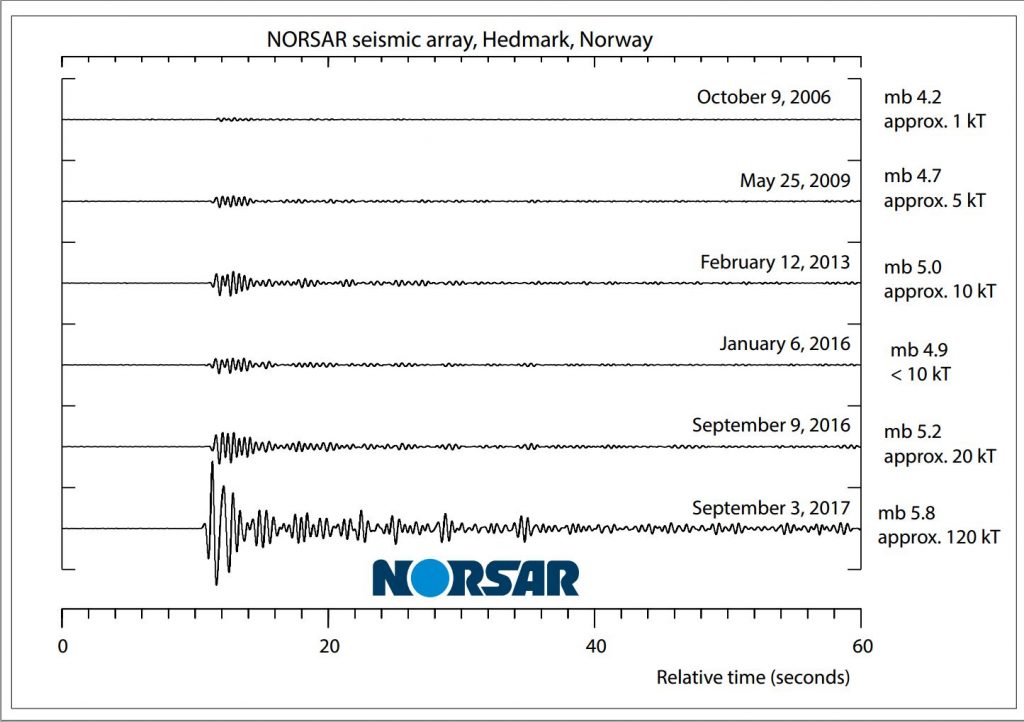

The figure shows (at the bottom) the seismic recording of the latest test in North Korea made at NORSAR’s station in Hedmark, Norway. The five upper traces show recordings at the same station for the five preceding tests, conducted by North Korea in 2006, 2009, 2013 and 2016 (two explosions in 2016). The 2017 test, is as can be seen from this figure, clearly the strongest so far. Credit: NORSAR.

When North Korea conducted a nuclear test in 2013, radioactive xenon was detected 55 days later, but this is not always possible. Any detection of such gases depends on whether or not a leak occurs in the first place, and how the gases are transported in the atmosphere.

Additionally, the seismic data cannot indicate the size of the nuclear device or whether it could be attached to a ballistic missile, as the North Korean government claims.

What seismology can give us is an idea of the size of the explosion by measuring the seismic magnitude. This is not straightforward, and depends on knowledge of exactly how deep the bomb was buried and the nature of the rock lying over the test site. However, by comparing the magnitude of this latest test with those from the previous five tests conducted in North Korea, we can see that this is a much larger explosion.

The Norwegian seismic observatory NORSAR has estimated a blast equivalent to 120 kilotons of TNT, six times larger than the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki in 1945, and consistent with the expected yield range of a hydrogen bomb.

Hurriquakes?

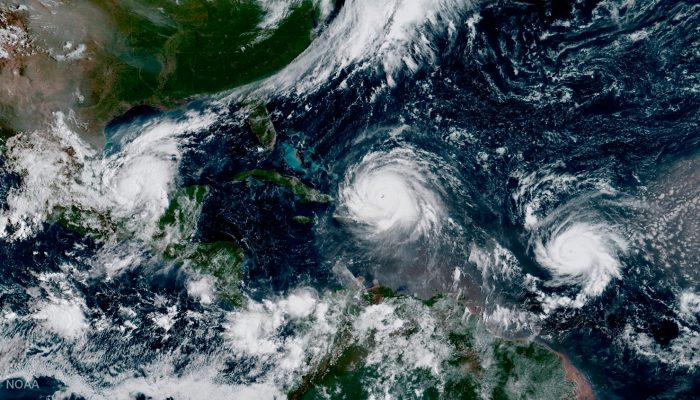

Nuclear tests are not the only hazard keeping our minds busy in the past few weeks. In the Atlantic, Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Katia have wreaked havoc in the southern U.S.A, Mexico and the Caribbean.

Hurricanes in the Atlantic can occur at any time between June and November. According to hurricane experts, we are at the peak of the season. It is not uncommon for storms to form in rapid succession between August, September and October.

The National Hurricane Centre (NHC) is the de facto regional authority for producing hurricane forecasts and issuing alerts in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific. For their forecasts, meteorologists use a combination of on the ground weather sensors (e.g. wind, pressure, Doppler radar) and satellite data.

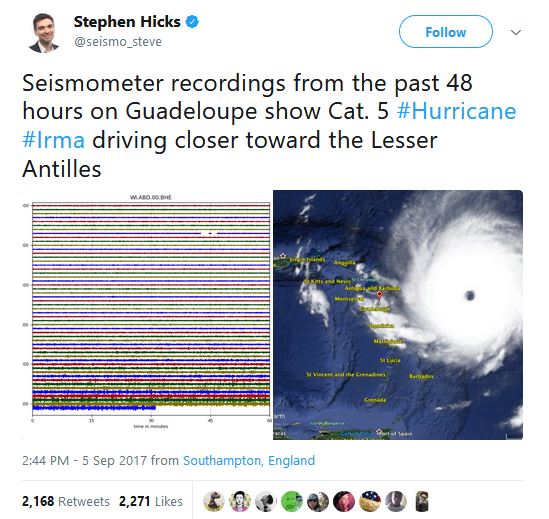

As hurricane Irma tore its way across the Atlantic, gaining strength and approaching the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, local seismometers detected its signature, sending the global press into a frenzy. It may come as a slight surprise to some people that storms and hurricanes also show on seismometers.

However, a seismometer detecting an approaching hurricane is not actually that astonishing. There is no evidence to suggest that hurricanes directly cause earthquakes, so what signals can we detect from a hurricane? Rather than “signals”, seismologists tend to refer to this kind of seismic energy as “noise” as it thwarts our ability to see what we’re normally looking out for – earthquakes.

The seismic noise from a storm doesn’t look like distinct “pings” that we would see with an earthquake. What we see are fairly low-pitched “hums” that gradually get louder in the days and hours preceding the arrival of a storm. As the storm gets closer to the sensor, these hums turn into slightly higher-pitched “rustling”. This seismic energy then wanes as the hurricane drifts away. We saw this effect clearly for Hurricane Irma with recordings from a seismometer on the island of Guadeloupe.

What causes these hums and rustles? If you look at the frequency content of seismic data from any monitoring station around the globe, noise levels light up at frequencies of ~0.2 Hz (5 s period). We call these hums “microseism”. Microseism is caused by persistent seismic waves unrelated to earthquakes, and it occurs over huge areas of the planet. One of the strongest sources of microseism is caused by ocean waves and swell. During a hurricane, swell increases and ocean waves become more energetic, eventually crashing into coastlines, transferring seismic energy into the ground. This effect is more obvious on islands as they are surrounded by water.

As the hurricane gets closer to the island, wind speeds dramatically increase and may dwarf the noise level of the longer period microseism. Wind rattles trees, telegraph poles, and the surface itself, transferring seismic energy into the ground and moving the sensitive mass inside the seismometer. This effect causes higher-pitched “rustles” as the centre of the storm approaches. Gusts of wind can also generate pressure changes inside the seismometer installation and within the seismometer itself, generating longer period fluctuations.

During Hurricane Irma, a seismic monitoring station located in the Dutch territory of St. Maarten clearly recorded the approach of the storm, leading to an intense crescendo as the eyewall crossed the area. As the centre of the eye passed over, the seismometer seems to have recorded a slightly lower noise level. This observation could be due to the calmer conditions and lower pressure within the eye. The station went down shortly after, probably from a power outage or loss in telemetry which provides the data in real-time.

Seismometers measuring storms is not a new observation. Recently, Hurricane Harvey shook up seismometers located in southern Texas. Even in the UK, the approach of winter storms across the Atlantic causes much higher levels of microseism.

It would be difficult to use seismometer recordings to help forecast a hurricane – the recordings really depend on how close the sensor is to the coast and how exposed the site is to wind. In the event of outside surface wind and pressure sensors being damaged by the storm, protected seismometers below the ground could possibly prove useful in delineating the rough location of the hurricane eye, assuming they maintain power and keep sending real-time data.

At least several seismic monitoring stations in the northern Antilles region were put out of action by the effects of the Hurricane. Given the total devastation on some islands, it is likely that it will take at least several months to bring these stations back online. The Lesser Antilles are a very tectonically active and complex part of Earth; bringing these sensors back into operation will be crucial to earthquake and volcano hazard monitoring in the region.

By Neil Wilkins (PhD student at the University of Bristol) and Steven Hicks (a seismologist at the University of Southampton)

References and further reading

GeoSciences Column: Can seismic signals help understand landslides and rockfalls?

NORSAR Press Release: Large nuclear test in North Korea on 3 September 2017

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Organization Press Release: CTBTO Executive Secretary Lassina Zerbo on the unusual seismic event detected in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

First Harvey, Then Irma and Jose. Why? It’s the Season (The New York Times)

IRIS education and outreach series: How does a seismometer work?

Kay

I am no scientist but there is no doubt in my mind that the bomb testing in North Korea is the cause to the earthquake in Mexico and all these hurricanes. If the plate in the earth shift nor naturally sea wakes will alter and that motion will cause desired temperature for hurricane to occur. There must be a correlation between the bomb testing and these earthquakes and hurricanes.

boris

Correlation is not causation. Hurricanes are large scale weather events that are the response of heat flows from the ocean to the atmosphere. The western part of much of North, Central and South America is where plate subduction occurs. This is accompanied by earthquakes and volcanic activity. North Korea probably did not have anything to do with hurricanes, nor the earthquake in Mexico. If you check https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/browse/m6-world.php you’d find that there were many seismic events in excess of M 6 before and after the test.

Angela Forret

I went Googling with the same question Julie had after thinking about physics and Energy. I appreciate the scientific evidence behind the scientists’ replies yet there is still a ‘what if’ element. Of course, typing this I realized i should just Google earthquake and hurricane events in 1945. Did, it showed two large earthquakes in the Pacific region, but quick scan of info didn’t indicate they were abnormally so. Hurricanes were more than ’44 but ’47 proved more activity and powerful. I do still wonder where all the excess energy goes once diffused.

Julie Andrews

My question was could the nuclear test shaking the Earth have caused the Mexican earthquake and the hurricanes to be worse .

Neil Wilkins

Hi Julie!

While it has been a very busy couple of weeks for high-profile seismic activity, the nuclear test, Atlantic hurricanes and Mexican earthquake are three unrelated events.

While earthquakes and explosions can trigger more seismic activity locally, the ground motion gets rapidly much weaker the further away you are from from the epicentre. From North Korea to the epicentre of the Mexican earthquake is over 12,000 km. The ground motion at these distances is only around one millionth of a centimetre – enough for a highly sensitive seismometer to detect, but nowhere near enough to cause slip on a fault.

The earthquake in Mexico was caused by the subduction of the Cocos tectonic plate under the North American plate. Earthquakes are common in the region, although this is the strongest to hit Mexico in a century.

There is also no evidence that seismic activity affects the formation of hurricanes. Instead, hurricanes depend on conditions in the atmosphere and Atlantic ocean. The sea surface temperatures this summer have been higher than average, which may account for the storms’ severity.

I hope this answers your question!

Stephen Hicks

Hi Julie,

There is certainly no scientific evidence to suggest the North Korea nuclear test caused the Mexico earthquake and worsened the effect of the Hurricane.

Although the nuclear test could be detected around the world, the ground motions are tiny, with movements on the order of 0.00001 cm.

Processes within the Earth and in the atmosphere are very complex and it is difficult to simulate every fine detail. Also, such events occur with a degree of randomness, so sometimes we end up with several natural hazards occurring within similar times, even though there is no physical connection between them.

Hope that helps and feel free to ask any more questions.