Drawing inspiration from popular stories on our social media channels, major geoscience headlines, as well as unique and quirky research, this monthly column aims to bring you the latest Earth and planetary science news from around the web.

Major story

The south Indian state of Kerala has suffered unusually heavy monsoon rainfall this month, triggering the worst flooding the state has seen in more than a century.

Officials have reported nearly 500 deaths, while more than one million people have been evacuated to over 4,000 relief camps.

Between 1 and 19 August, the region received 758.6 milimetres of rain, 2.6 times the average for that season. In just two days (15-16 August), Kerala sustained around 270 milimetres of rainfall, the same amount of rainfall that the entire state receives in one month typically, said Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to BBC News.

Due to the heavy downpours, rivers have overflowed, water from several dams has been released, and lethal landslides have swept away rural villages.

“Officials estimated about 6,000 miles (10,000km) of roads had been submerged or buried by landslides,” reported the Guardian. “Communications networks were also faltering, officials said, making rescue efforts harder to coordinate.”

Experts report that the event’s severity stems from many factors coming together.

For instance, a recent study led by Koll has shown that in the past 50-60 years, monsoon winds have weakened, delivering less rain on average in India. However, the distribution of rainfall is uneven, with long dry spells punctuated by heavy rainfall events. Koll’s research suggests that central India has experienced a threefold rise in the number of widespread extreme rain events during 1950-2012. In short, it doesn’t rain as often; but when it rains, it pours.

Scientists also say that increased development in the region had exacerbated the monsoon’s impact.

For example, usually when storms release heavy rainfall, much of that water is absorbed or slowed down by vegetation, soil, and other natural obstacles. However, scientists point out that “over the past 40 years Kerala has lost nearly half its forest cover, an area of 9,000 km², just under the size of Greater London, while the state’s urban areas keep growing. This means that less rainfall is being intercepted, and more water is rapidly running into overflowing streams and rivers.”

To make matters worse, increased development can also change how effectively rivers handle heavy downpours. For instance, canals and bridges can make rivers more narrow and can create sediment build-up, which slows water flow. “When there is a sudden downpour, there is not enough space for the water so it floods the surrounding area,” explains Nature.

Some experts have added that badly-timed water management practices are also partly to blame for the flood’s devastation on local communities.

“A contributing factor is that after the heavy rain, authorities began to release water from several of the state’s 44 dams, where reservoirs were close to overflowing. The neighbouring state of Tamil Nadu also purged water from its over-filled Mullaperiyar dam, which wreaked yet more havoc downstream in Kerala,” Nature adds.

While floodwaters began to recede in late August, rescue teams are still searching submerged neighborhoods to deliver aid and evacuate survivors.

What you might have missed

Water on moon confirmed

Recent research published this month suggest that there is almost certainly frozen water on the moon’s surface.

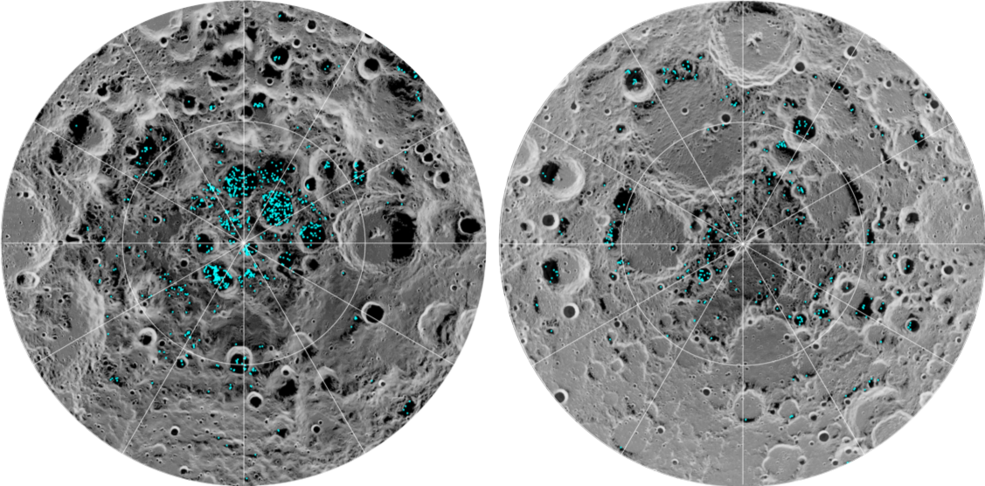

The image shows the distribution of surface ice at the Moon’s south pole (left) and north pole (right). Blue represents the ice locations, plotted over an image of the lunar surface, where the gray scale corresponds to surface temperature (darker representing colder areas and lighter shades indicating warmer zones). (Credit: NASA)

“Previous observations indirectly found possible signs of surface ice at the lunar south pole, but these could have been explained by other phenomena, such as unusually reflective lunar soil,” NASA officials said in a published statement.

Now, scientists involved with the new study claim that they’ve found definitive evidence that ice is located within craters on the moon’s north and south poles.

During daylight hours, the moon’s surface can be brutally hot, often reaching temperatures as high as 100 degrees Celsius. However, due to the moon’s axial tilt, some parts of the lunar poles don’t receive sunlight. Scientists estimate that some craters situated within these permanently dark polar regions are cold enough to sustain pockets of water-ice.

Because the moon’s poles are so dark, scientists have had a hard time studying the lunar craters. But Shuai Li, a planetary researcher at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and lead author of the study, and his colleagues tried a creative way to shed some light on shadowed craters, using data collected from India’s Chandrayaan-1 lunar probe ten years ago.

“They peered into dark craters using traces of sunlight that had bounced off crater walls,” reports the New York Times. “They analyzed the spectral data to find places where three specific wavelengths of near-infrared light were absorbed, indicating ice water.”

As of now, the researchers still aren’t sure how much ice there is, or how it found its way to the moon’s poles. But if enough accessible ice exists close to the lunar surface, the water could be used as a resource for future missions to the moon, from a source of drinking water to rocket fuel.

Mapping Earth’s winds from above

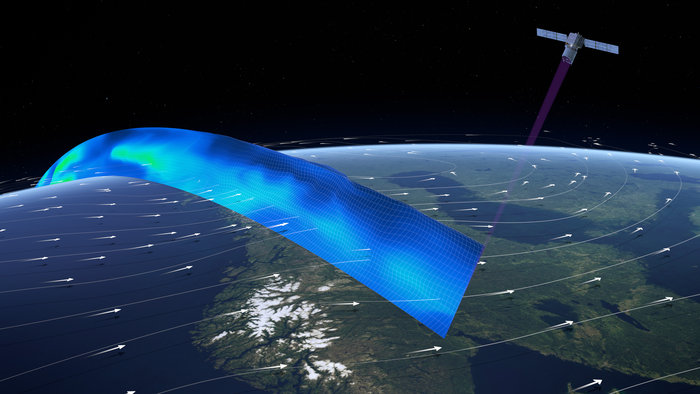

Also this month, scientists from the European Space Agency launched a satellite that will profile the world’s winds, in hopes that the data will greatly improve weather forecasts and provide insight for long-term climate research. The satellite, named Aeolus after the celestial keeper of the winds in Greek mythology, was sent to orbit from French Guiana on Wednesday 22 August.

“The rocket was due to lift off on Tuesday, but the launch was postponed – ironically – due to high altitude winds,” reports BBC News.

Aeolus profiling the word’s winds (Credit: ESA)

Equipped with a Doppler wind lidar, Aeolus will send powerful laser pulses down to Earth’s atmosphere and measure how air molecules and other particles in the wind scatter the light beam.

Researchers expect that wind data from Aeolus will greatly improve current efforts to forecast storms, especially their severity over time. While scientists have many ways to measure wind behavior, current methods are unable to capture wind movement from all corners of the Earth. Aeolus will be the first mission to monitor winds across the entire globe.

Using data collected by Aeolus, experts estimate that the quality of forecasts will increase by up to 15% within the tropics, and 2-4% outside of the tropics.

“If we improve forecasts by 2%, the value for society is many billions of dollars,” said Lars Isaksen, a meteorologist at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), to Nature.

Learn how Earth’s wind is generated and why we need to measure it. (Credit: ESA)

Links we liked

- STEVE the purple beam of light is not an aurora after all

- A new visualization turns global warming into pop art

- How much hotter is your hometown than when you were born?

- Explore your inner child by painting science with pixels

- The festivals mixing music and science

The EGU story

Do you enjoy the EGU’s annual General Assembly but wish you could play a more active role in shaping the scientific programme? Now is your chance! Help shape the scientific programme of the 2019 General Assembly.

Before the end of today (6 September), you can suggest:

- Sessions (with conveners and description), or;

- Modifications for current ones

- Suggestions for Short courses (SC) will also take place during this period

- From now until 18 January 2019, propose Townhall and splinter meetings

This month we released two press releases from research published in our open access journals. Take a look at them below:

Landslides triggered by human activity on the rise

More than 50,000 people were killed by landslides around the world between 2004 and 2016, according to a new study by researchers at UK’s Sheffield University. The team, who compiled data on over 4800 fatal landslides during the 13-year period, also revealed for the first time that landslides resulting from human activity have increased over time. The research is published today in the European Geosciences Union journal Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences.

Deadline for climate action – Act strongly before 2035 to keep warming below 2°C

If governments don’t act decisively by 2035 to fight climate change, humanity could cross a point of no return after which limiting global warming below 2°C in 2100 will be unlikely, according to a new study by scientists in the UK and the Netherlands. The research also shows the deadline to limit warming to 1.5°C has already passed, unless radical climate action is taken. The study is published today in the European Geosciences Union journal Earth System Dynamics.

And don’t forget! To stay abreast of all the EGU’s events and activities, from highlighting papers published in our open access journals to providing news relating to EGU’s scientific divisions and meetings, including the General Assembly, subscribe to receive our monthly newsletter.

Ltrani

All very interesting and informative.