Why does some research make it into the main stream media, while so many stories languish in the expanse between the lab bench and research papers? The answer isn’t straightforward. A variety of factors come into play: is the research newsworthy; is it timely; does it represent a ground-breaking discovery; or is it of human and societal interest?

Newsworthiness isn’t the be all and end all. Sometimes, you’ve got to be proactive about getting your research noticed. If you think your work features a story worth telling, it might be time to dare and pitch it to a journalist or editor.

Most researchers aren’t familiar with how the media works, let alone how to contact and persuade a journalist that their research is worthy of a news item. At this year’s General Assembly we hosted a short course on this very topic. It featured a panel of science journalists and a scientist with media experience who shared their views on what makes research newsworthy and how to get your work noticed. Here, we share a few highlights from that session.

Is my research newsworthy?

While what we said in the introduction stands, i.e. newsworthiness is not the be all and end all, the fact remains: there has to be something about your research which makes it interesting to the general public and worth reporting about for a journalist.

Ground-breaking findings instantly tick the box, but the media will also be interested in results which have a big impact on people’s daily lives, relate to current events and/or include striking images or videos (among others). Scientist-turned-journalist Julia Rosen has a comprehensive list of what does (and doesn’t) make research newsworthy. When trying to decide whether your research fits the bill, you might also find this EGU guide useful.

The process of doing science is often the key to a great story but it is often overlooked.

“Don’t take your methods for granted,” says freelance journalist Megan Gannon, “fieldwork and lab work is inherently fascinating to people who have never done that.”

This GeoLog story, featuring PhD student Thomas Clements and his study of decaying fish guts, livers and gills, to understand how organisms become fossils, is a perfect example. Thomas presented new results at a press conference at the 2016 General Assembly, but his research methodology was just as fascinating as his data and became the focal point of the story.

The impostor syndrome

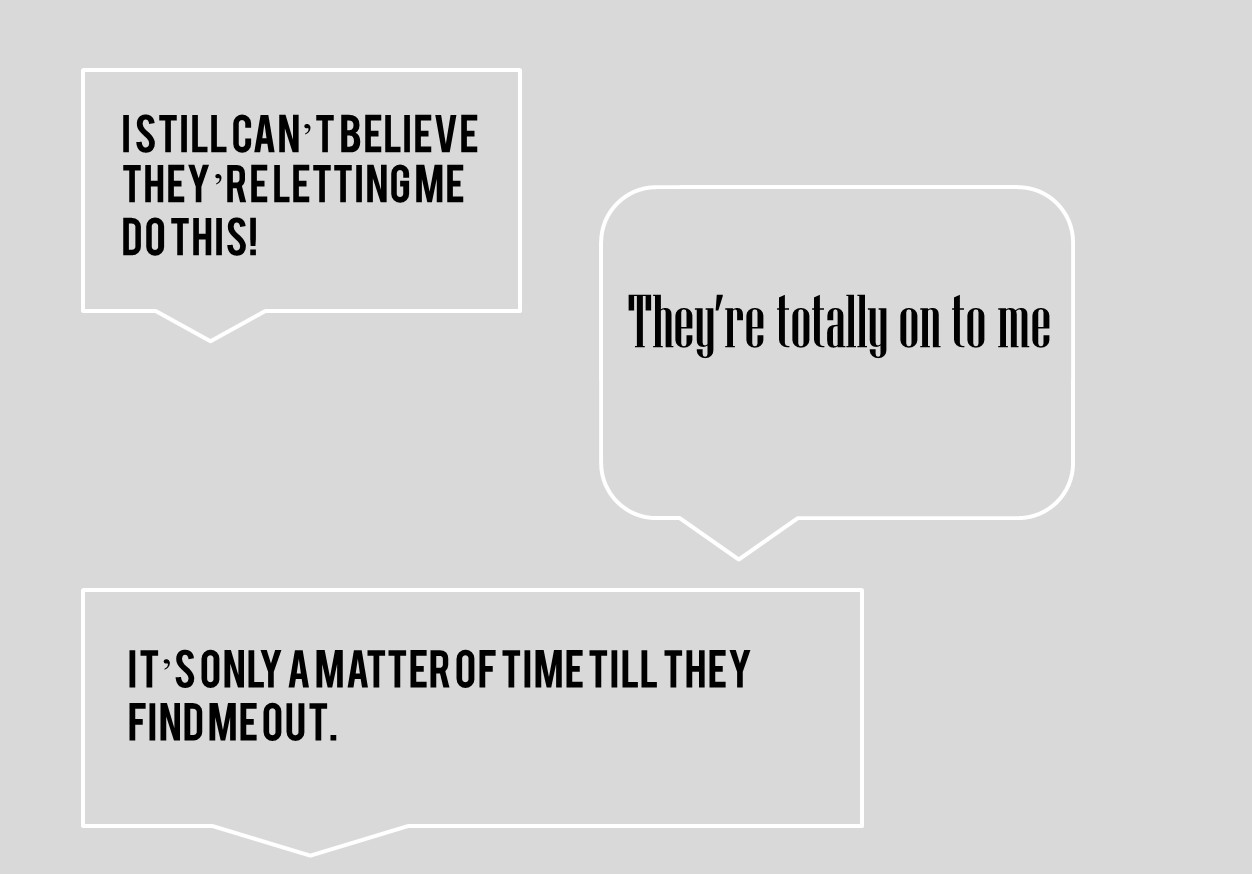

Even if a scientist knows (or has an inkling that) their work is newsworthy they’ll likely be faced with an age-old fear, rife among academics: am I smart or talented or deserving or experienced (insert an alternative synonym of your choice here) enough to put my work forward to a journalist? Is the work itself good enough?

The fear of being found out: is my work good enough; should I really be putting it out there? Credit: modified from original by Rhian Meara

Rhian Meara, a lecturer in geography and geology at Swansea University, recognises that this is a common feeling that she’s experienced many a times, both on location filming on TV and when asked to take part in the short course, but one which shouldn’t hold you back. As an expert in your area you are best placed to tell the story of your findings and work.

Overcome that fear by playing to your strengths and use them to your advantage. For example, are you fluent in a language other than English? This skill might mean you could become the go-to-scientist for coverage of Earth science related stories in your local area and/or language.

Working with the media

Convinced that your research is newsworthy and armed with the courage to take the next step? Before you do, there are a few, final, things to consider.

When approaching a journalist or editor about your work, “you need to pitch a story, not a topic: give journalists stories and context. Getting news across to readers requires giving it a deeper meaning and setting it in the big picture,” Megan points out.

Simply laying out the facts won’t cut it. You need to make your research come to life so it gets noticed.

There is also a reality you need to reconcile if you are planning on pitching your research to the media. Journalists serve their readers, not the scientists whose story they are telling.

“Even if scientists want to promote their research by reaching out to journalists, they should be aware that our role is not to promote their agenda, but to inform the public in an objective manner,” explains Megan.

But that doesn’t mean they will set-out to misrepresent your work either. Be patient with journalists if they ask questions, sometimes repeatedly, about your research. They may not be familiar with the subject, but importantly, they are trying to capture the essence of the science and make it accessible to a broad audience. To do this, they need to ask questions; sometimes, lots of them.

Communication issues

Precisely because the media needs to serve their readers and viewers, there is no doubt that there might be a clash when it comes to reporting particular findings. Being aware of it is important, but there are ways you can prepare in advance to minimise misunderstandings.

“Be careful of promoting unpublished results,” warns Andrew Revkin, a science and environmental writer for The New York Times (among others).

Your unpublished study has the potential to attract a lot of media attention, but what happens if the paper requires major revision, or worse, isn’t published?

The use of jargon can also lead to misinterpretation – “words that mean something to scientists might mean something entirely different to the public and reporters,” Andrew points out.

The obvious ones, say for instance (climate) model vs. (fashion) model, can usually be easily clarified. It’s the more subtle ones which present the biggest challenge: uncertainty, risk.

A challenge for scientists, and science journalists, Revkin said, is conveying that, in scientific analysis, bounded uncertainty is a form of knowledge. For more ideas, read a lecture he gave in 2013 in Tokyo: Exploring the Challenges and Opportunities in the New Communication Climate.

Communicating the nuances of what is meant by such terms is difficult; it’s best to consult a media expert for alternatives rather than risk amplifying misunderstanding.

A little help

Still nervous about the process of pitching your research to a journalist or editor?

Scientists needn’t embark on the venture on their own. In all likelihood your research institute or university will have a press officer: someone who has expertise in dealing with the media, pitching stories to journalists, and knows what makes for newsworthy research. Failing that, approach your funders who will likely have a media relations team.

If you think your research has the potential to be newsworthy, get in touch with them! They’ll be able to help you find out whether indeed your research could interest journalists, and with all the steps we touch upon in this post and more!

More and more, the ability to communicate science is becoming a priority for researchers. If this is the case for you too, but you aren’t sure how to get started, there are a number of resources and courses which can help you develop your media skills. This post, in the blog Geology Jenga, has a list of some courses and resources available.

By Laura Roberts, EGU Communications Officer (with thanks to Megan Gannon, Rhian Meara, Andrew Revkin and Christina Reed)

This blog posts based on the presentations by Megan Gannon, Rhian Meara and Andrew Revkin at the ‘Short Course: How to pitch your research to a journalist or editor (SC45)’ which took place at the 2016 EGU General Assembly in Vienna and was moderated by Christina Reed. The full presentations can be accessed here.