GeoLog followers will remember our previous report on Citizen Geoscience: the exciting possibilities it presents for the acquisition of data, whilst cautioning against the exploitation of volunteered labour. This blog presents a Citizen Science platform that goes beyond data collection to analysis, specifically for geological changes in remote sensing imagery of Mars. Jessica Wardlaw, a Postdoctoral Research Associate in Web GIS, at the Nottingham Geospatial Institute, introduces ‘iMars’ and explains 1) its scientific mission and 2) why imagery analysis is especially suitable for a crowd sourcing approach, so that you might consider where and how to apply it to your project.

Imagine, just for a moment, that the Mars Geological Survey invited you to an interview for the position of Scientist in Charge. Why and how would you reconstruct the geological past for a remote planet such as Mars? Where would you start? Earth is the “Goldilocks” planet, not only for human habitation but for geologists too, who can sample and test rock to understand the evolution of the Earth’s surface on which to base well-established theories such as plate tectonics. To understand the geological past and processes of remote planets, however, requires different approaches.

Planetary scientists investigate the climate and atmosphere, and the geological terrain, of planets to further understanding of our own place in the solar system. Mars provides a scintillating snapshot of early Earth; whilst some scientists contend that plate tectonics has historically happened on Mars, 70% of its surface dates from the moment it formed and provides a platform from which to view Earth in its infancy. In fact, despite our limited knowledge of Mars, it has already informed our understanding of Earth, inspiring James Lovelock’s Gaia theory. Imminent missions to the red planet are also already exploiting geological information to inform landing sites and routes of roving vehicles on Mars. The more information scientists have, the more likely missions are to land in suitable locations to successfully pursue scientific goals, such as understanding the ability of the Martian environment to support life and water, both now and in the past, which could further theories on the origins of the solar system, life on Earth, and Earth’s destiny.

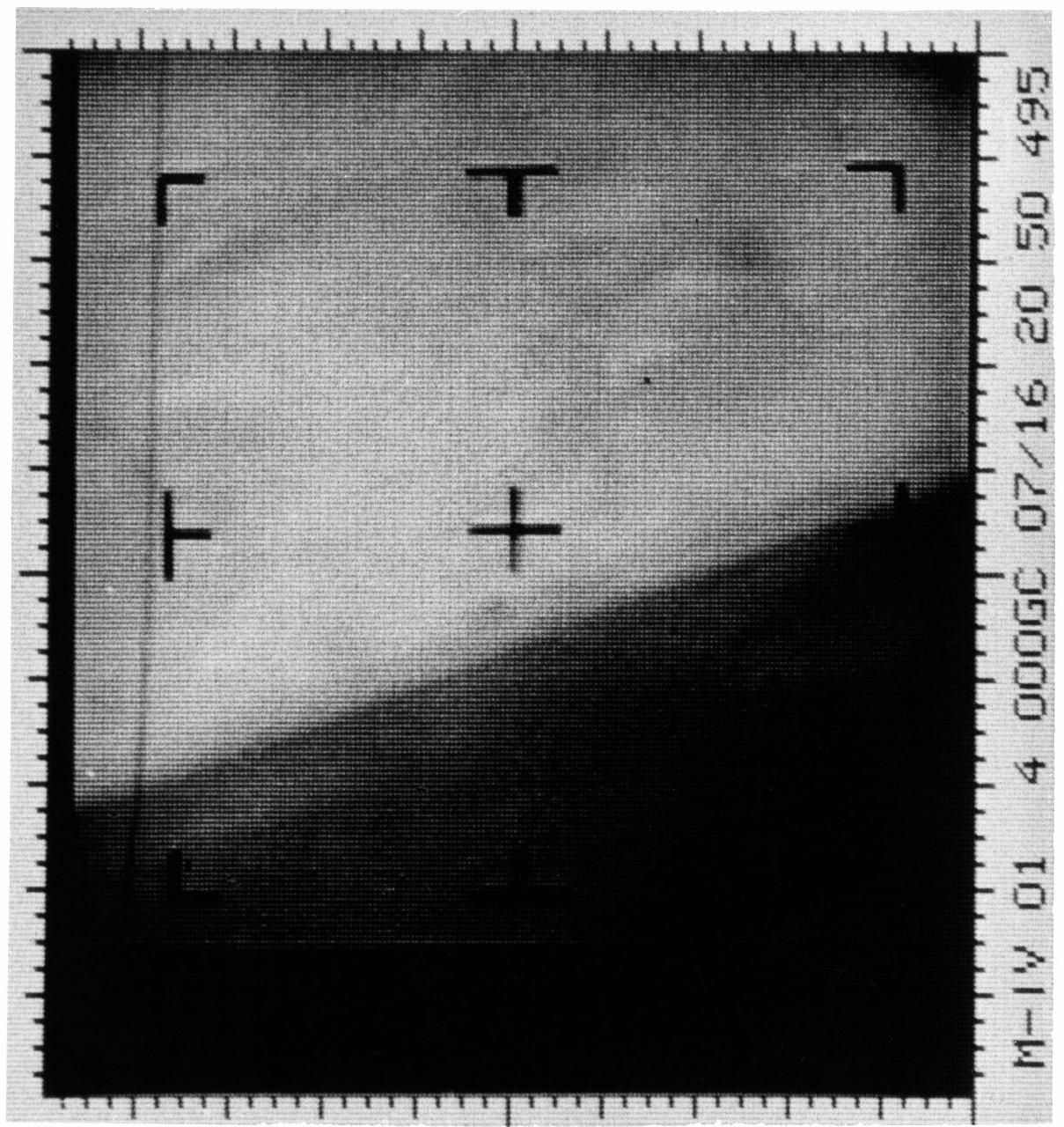

Many will remember this summer for the astonishing images that arrived from Pluto, but 50 years ago, almost to the day, people celebrated the first successful fly-by mission to Mars. Mariner 4 took 21 images from a distance 6,000 miles, which, after the initial excitement, disappointingly revealed that Mars had a Moon-like cratered surface, and led to a long-held misconception of a dead, red planet. It was in 1976 that two Viking landers touched down on the red soil for the first time, paving the way for further Martian missions, with the first mission of the European Space Agency’s ExoMars programme launching next year.

The first Mars photograph and our first close-up of another planet. A representation of digital data radioed by the Mariner 4 spacecraft on 15th July 1965. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Dan Goods)

Scientists analyse the size and density of craters from meteorite impacts to age the surface. The theory goes that smaller meteorites collide with a planet much more frequently than larger ones, and older surfaces have more craters because they have been exposed for longer. Advances in imaging technology since then now provide scientists with greater granularity than ever before and glimpses of other geologic features, recognisable from the surface of the Earth; sand dunes, dust devils, debris avalanches, gullies, canyons all appear and tell us about the planet’s climatic processes. The Planet Four website is just one example.

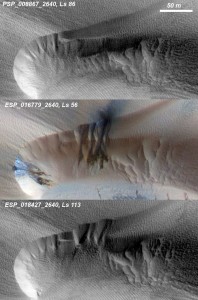

The images taken of Mars over the last forty years reveal changes on the surface that indicate invaluable information that help us to understand the climate and geology of the planet. Changes are visible in imagery over a variety of timescales, from rapidly-moving dust devils (much bigger that the one that once trapped me in Death Valley), seasonal fluctuations of the polar ice caps and recurring slope lineae (recently reported to indicate contemporary water activity) polar ice caps and the snail-slow shaping of sand dunes.

Three images of the same location taken at different times over one Martian year show how the seasonal fluctuation of the polar cap of condensed carbon dioxide (dry ice), between its solid and gaseous state, destabilises a Martian dune at high altitude to cause sand avalanches and ripple changes. (Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

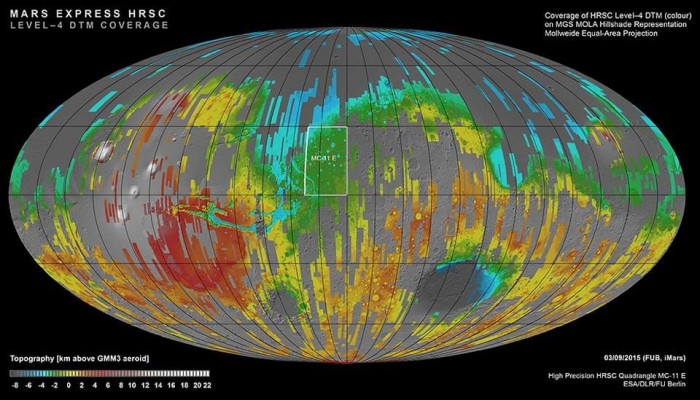

The quality and coverage of these images, however, varies greatly due to atmospheric conditions and tilt of the camera amongst other reasons. To create a consistent album of imagery, that we can confidently compare and use to identify geological changes in the images, requires considerable computational work. Images from across as much of the Martian surface as possible must be processed to remove those of poor quality and correct for different coordinate systems (co-registration) and terrain (ortho-rectification).

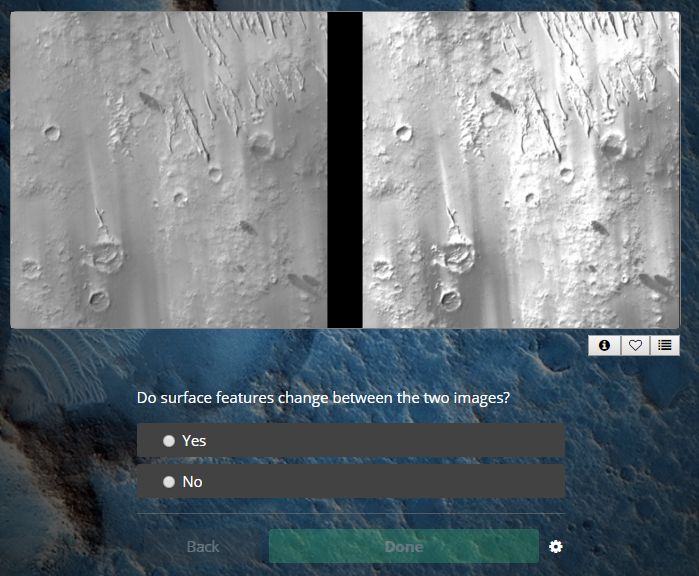

The iMars project is applying the latest Big Data mining techniques to over 400,000 images, so that they can be used to compute and classify changes in geological features. On a Citizen Science platform, Mars in Motion, volunteers will define the nature and scale of changes in surface features from ortho-rectified and co-registered images to a much greater detail. Human performance is inherently variable in ways we cannot fully control, either, in the same way that we can control the performance of an algorithm. Although we are investigating this too, this would require another blog post! For now I will describe the reasons why we are using a crowd-sourcing approach for this project so that you might consider how you could apply it to your research.

First of all, humans have evolved over millions of years to identify subtle variations in visual patterns to a more sophisticated level than computers currently can. Computers can execute repetitive tasks and store an infinite amount of information with far less impact on their performance than humans; the human mind, however, has proved to be too flexible and creative for computers to fully replicate, with the success of Citizen Science projects such as Galaxy Zoo, which has so far resulted in 48 academic publications. The slow seasonal shift of sand dunes on Mars, for example, would require a computer algorithm of inordinate intelligence to identify, as previous attempts to automatically detect impact craters, valley networks and sand dunes in images of Mars have found. Recent research has resulted in some very sophisticated algorithms for image analysis, but detection of changes in such a range of geological features over the range of spatial and temporal scales that we are looking to do is computationally complex and expensive. Without sending somebody to Mars, how do we know whether the computer is correct? Machine learning algorithms can only calculate what you ask them to, so are ill-equipped to make the sort of serendipitous discoveries of the unknown required in the detection of change. Volunteers in the Mars in Motion project will seek differences (Figure 4), rather than similarities, between the images and it is inherently challenging to program a computer to find something that you don’t even know to look for.

Secondly, we have so much data that scientists could not possibly do all of this themselves! In many areas of science and humanities, but especially in Earth and Planetary observation, Big Data capture is growing at an astronomical rate, far faster than resources and techniques for its analysis can keep up so that we are increasingly unable to handle it. This is where geoscientists have started to join the trend for recruiting volunteers to analyse imagery with some success; through large crowd-sourcing image analysis projects, like TomNod, citizens continually contribute interpretation of images for social and scientific purposes. The number of volunteers, however, is finite and the increase in data places more and more demand upon their time. Researchers using the Citizen Science approach must now carefully consider how their projects can utilise volunteers’ time effectively, efficiently and ethically.

Third and finally, a crowd-sourcing approach exposes the public to improvements in imaging technology and brings the dynamic nature of the Martian surface to life. This can only improve the chances of space exploration receiving further funding and entering classrooms through the way it combines many areas of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Serendipitously, the engagement of the public also increases the number of pairs of eyes that analyse the images and, as such, the confidence with which scientists can use their classifications. As we collect more and more data, image analysis will necessarily require collaboration between humans and computers, as well as between volunteers and researchers, to manage it.

I hope this post gives you an insight into how we are applying the Citizen Science to consider how it might help your research too. There is actually no better time to try setting up a Citizen Science project with the launch of the Zooniverse project builder, which makes it easier than ever before to build your own project.

By Jessica Wardlaw, researcher at the University of Nottingham

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under the iMars grant agreement no. 607379.

Visit www.i-mars.eu and follow @JessWardlaw for updates on iMars and Mars in Motion.

Pingback: Sweet (Two Thousand and) Sixteen | The GeographiGal