During the European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna, I caught up with Phil Heron, a Newcastle-born geodynamicist at Durham University, UK. Earlier this year he won an EGU outreach grant to engage young offenders with geoscience subjects and help improve their employability. He tells us how he started working in prisons and shares what we can learn from his experience.

How did the project start?

I realised there weren’t many science programs in England in prison. I wanted to try and build one that can be easily transported to different prisons. My original idea was to do a workshop or two on geodynamics, but then I saw there was a need for this – every person I spoke to, whether they were prison education officers or inmates was like “Ah, we love science.” There was a real appetite.

How do you make geoscience relevant to prison residents?

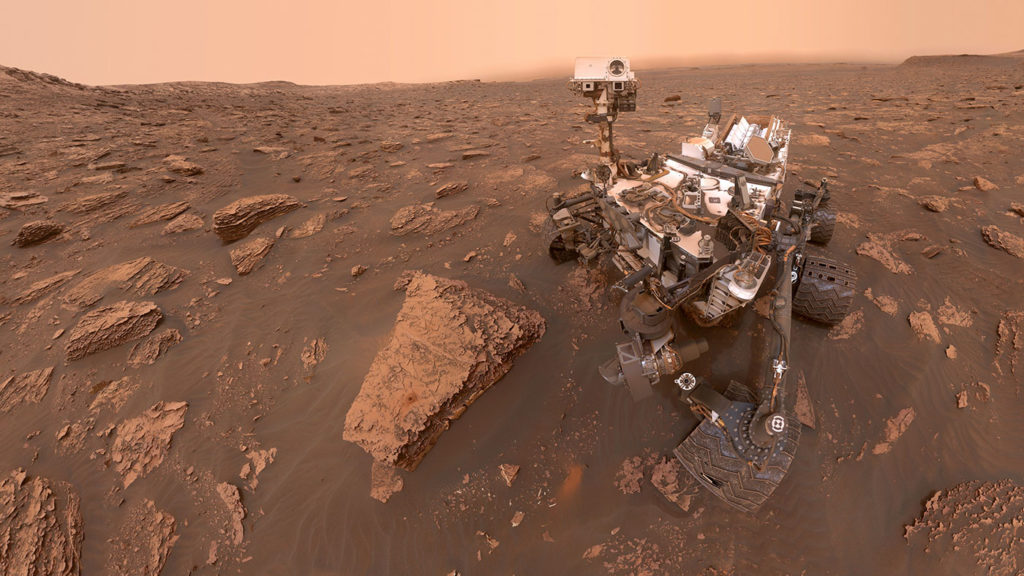

I was lucky enough to chat to inmates who had been part of a criminology course at Durham University called Inside Out. I could listen to their thoughts about my ideas, absorb their enthusiasm and their reservations. Some of the inmates said “the reason why the Inside Out criminology course works for us is because we’ve all committed crimes. It’s relatable.” That was a thunderbolt for me. How can I make volcanoes relatable? How can I make missions to Mars relatable?

I broke it down into thought processes. As scientists we have similar ways of thinking. What don’t we understand? What are we looking to solve? How do we get to a conclusion? By making experiments. It’s a thought process that we can apply, not just to science, but to everyday life. If you have a problem in your own life, you work through this way of thinking. It’s not necessarily about the scientific topics, but the scientific way of thinking.

The course is called Think Like a Scientist.

What motivated you to run the course, and what would you like it to achieve?

I see the course as a pathway to education and rehabilitation. Our first course was in a women’s prison and there was overwhelmingly positive feedback – lots of enthusiasm for education.

This year, I received the EGU Public Engagement Grant and will be using these funds to run something similar at a young offender’s institution. I’m trying to link up with employers and show that analysis, communication – the skills students learn in Think Like a Scientist – are the sorts of things employers are looking for. Employability is that one key thing that helps reduce the chances of reoffending. I want the course to help increase employability for residents on release.

A lot of prison employability comes from practical, manual roles, but it doesn’t have to. There’s a need for people to do STEM careers. If residents like science, this could be a way forward for them once they’re released.

What is a typical day in the course like for residents?

The first five days are very similar – for a reason. You need to build trust and consistency to really embed into the class. The classes themselves are broken down into 15-minute segments to keep it varied and engaging. The inmates come in, the door is locked and the next movement of the prison isn’t for another 2.5 hours. It’s a huge amount of time to teach.

There is no PowerPoint or anything like that, but I’ll bring lots of handouts: things for the students to read, discuss or work through. We’ll go over big, impactful case studies, like the year without a summer that followed the Krakatoa eruption or the 2010 eruption in Iceland, which everyone remembers. I’ll start with smaller eruptions that everyone can relate to, before moving onto supervolcanoes and the like. It gives people some perspective.

What was the most enjoyable part of the project?

I’ve taught in various different environments over the past eleven years and the students I had in this course are by far the best I’ve ever had. It is a real joy to be in a room full of people who are just desperate to learn and to better themselves.

As a teacher, you up your game when the students are upping theirs.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to do outreach in prisons, or with a challenging new audience?

Listen, listen, listen. Spend a long time listening. I took everyone’s advice and really analysed it for a long time. Science really grabs people’s imagination. If it grabs your imagination then it will definitely capture that of someone in a challenging environment.

Science really is for everyone. I’d encourage anyone who wants to conduct outreach with anyone from a more unusual background to give it a try.

Phil is always looking to learn from others. If you are an employer in STEM, let him know what steps someone would need to take to pursue a career in science after release. These practical tips will help support his work with prison residents and young offenders.

Interview by Sara Mynott, EGU Press Assistant