The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) prepares and publishes extensive Assessment Reports on the scientific, technical and socio-economic knowledge on climate change, including its impacts, future risks, and likely scenarios based on the actions that humanity takes. In their sixth Assessment Report (AR6), the IPCC’s certainty and warnings were clearer than ever. This month’s GeoPolicy blog post outlines a few of the key points but it’s not an extensive overview and does not include the varying levels of certainty given in the full report. We therefore also recommend that you read the 40 page summary for policymakers here or the full 3949 page Assessment Report here.

The IPCC’s Assessment Reports take stock of the world’s climate change knowledge by assessing the current scientific literature. These reports included the work of hundreds of experts and thousands of peer-review studies and the findings then play a vital role in supporting evidence-based climate policy around the world. The AR6 report represents the world’s most current knowledge of climate change and provides an even more accurate assessment of our current status than ever before due to new climate model simulations, analyses, and methods that can combine a wider range of climate variables. This has helped the IPCC scientists to give greater attribution to human influence for extreme weather events such as heatwaves, droughts, and tropical cyclones compared with the AR5 report.

The current state of the climate

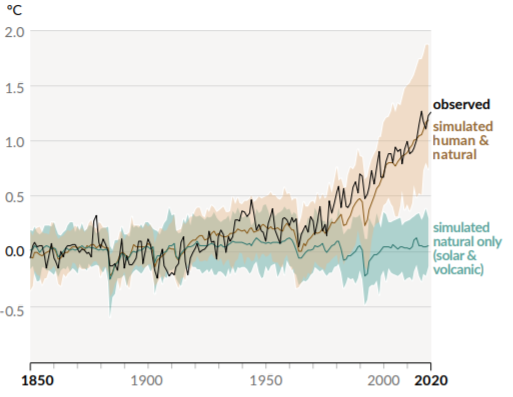

The IPCC’s AR6 reported that global surface temperature from 2011 to 2020 was 1.09°C higher compared with that in 1850–1900, the period used as a pre-industrial baseline. From this, the best estimate of human-caused global surface temperature was 1.07°C with each of the last four decades being successively warmer than any decade that preceded it.

History of global temperature change and causes of recent warming. Credit: the IPCC’s AR6

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations in 2019 were also found to be higher than at any time in the last 2 million years, at least. Even more worryingly, based on the evidence, the report stated,

It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred. […] Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe.

These widespread changes to the Earth’s atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere are having a huge range of economic, environmental and social consequences that will continue to grow as the global temperature increases, including increased food and drinking water insecurity, loss of biodiversity and ecosystem resilience, and greater damage to physical infrastructure.

So… not good news. Very, very bad news. But can we still turn it around?

Our possible climate futures

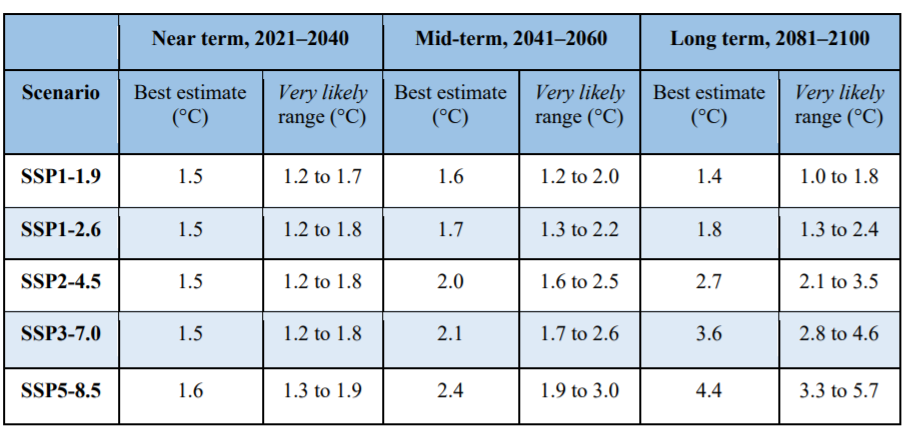

AR6 provided five different scenarios based on our emissions path and projections. These scenarios are a result of many different calculations of complex and dynamic systems and aim to provide alternative images of what our future could look like. These futures are all very different and dependent on the policies and actions that we take now.

The IPCC’s five different emissions scenarios. Credit: the IPCC’s AR6

All but one of these scenarios shows us reaching and staying above 1.5°C warming compared with pre-industrial levels, consequently breaking the 1.5°C limit of warming pledged made during the Paris Climate Agreement. Warming of 1.5°C and 2°C will be exceeded this century unless serious reductions greenhouse gases are achieved. In the highest emission scenario (SSP5-8.5), AR6 explained that reaching 1.5°C warming is very likely before 2040 and is still “likely” under intermediate or high emissions. Much of what was outlined in the IPCC’s 2018 special report on 1.5C (SR15) in terms of how close the world was to breaching the limit and how we can avoid it, is still true and relevant.

The lowest emissions scenario, SSP1-1.9, shows that stabilising the climate below 1.5°C is still possible. However, even in this “best-case scenario”, we would see levels of heating resulting in more frequent and intense heatwaves, storms, droughts and floods. We would also continue to see sea-level rise and ocean acidification. These impacts are thought to be more severe for low-income countries: it’s expected that developing countries will bear 75-80% of the costs of climate change, according to a 2019 report by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. If 1.5°C warming is reached, 500 million more people may be exposed to water stress whilst up to 4.5 billion people could face more frequent, intensified heatwaves. A potent mixture of factors – such as living in tropical regions more susceptible to the impacts of climate change, and less access to resources and infrastructure to help people mitigate and recover from disasters – combine to make developing nations more vulnerable; since 2000 alone developing nations have suffered casualties from disasters related to natural hazards at a rate seven times greater than high-income nations.

Despite all this, SSP1-2.6 would represent a much less devastating outcome for the environment and society than reaching 2°C. As AR6 states,

With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes continue to become larger.

As our CO2 emissions increase, the way in which the planet deals with them will also shift. While land and ocean carbon sinks will, in absolute terms, take a progressively larger amount of CO2, the proportion of emissions taken up by land and ocean will decrease. This is very likely to result in a higher proportion of emitted CO2 remaining in the atmosphere. Consequently, higher CO2 emissions scenarios will result in the magnitude of feedbacks between climate change and the carbon cycle becoming both larger and more uncertain.

So how do we save the planet?

Despite AR6 outlining many hard truths and some incredibly scary futures, every fraction of a degree of warming matters. Our best chance is to take serious action on climate change across every sector and all fronts right now!

To reach either the SSP1-1.9 (the best-case scenario), net global CO2 emissions will need to fall by approximately 45% of 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero by approximately 2050, followed by varying levels of net negative CO2 emissions. It cannot be overstated how difficult and how important reducing our CO2 emissions by 45% of 2010 levels by 2030 really is. If we’re to achieve this, we need to start making stronger policies and plans to reduce our emissions… ideally yesterday! While scientists should stay impartial rather than advocating for specific policies, the science on climate change is clear. Sharing what that science is and what the consequences of any action (or inaction) are likely to be is exactly what science for policy is all about! You can learn more about how you can best interact with policymakers on climate issues by watching the #vEGU21 Union Symposia, A Climate and Ecological Emergency: Can a pandemic help save us…?

SSP1-1.9 scenario and how we can reach it will hopefully be the main focus in the upcoming Conference of the Parties (COP26). COPs provide world leaders, policy workers, and scientists leaders with an opportunity to discuss and negotiate how best to make sure we limit climate change and stay under 1.5°C of warming. This November, Governments from 197 countries will meet in Glasgow with updated plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and hopefully stick to the IPCC’s SSP1-1.9 (the best-case scenario). The world will be watching to see decisions being made that will impact all of our futures.