On top of a steep cliff standing out from the surrounding countryside, lies the small town of Civita di Bagnoregio, one of the most famous villages of Italy. It is often called the dying town, although more recently people have started to refer to it as fighting to live. What this little town is fighting against is the threat of erosion, as its walls are slowly crumbling down.

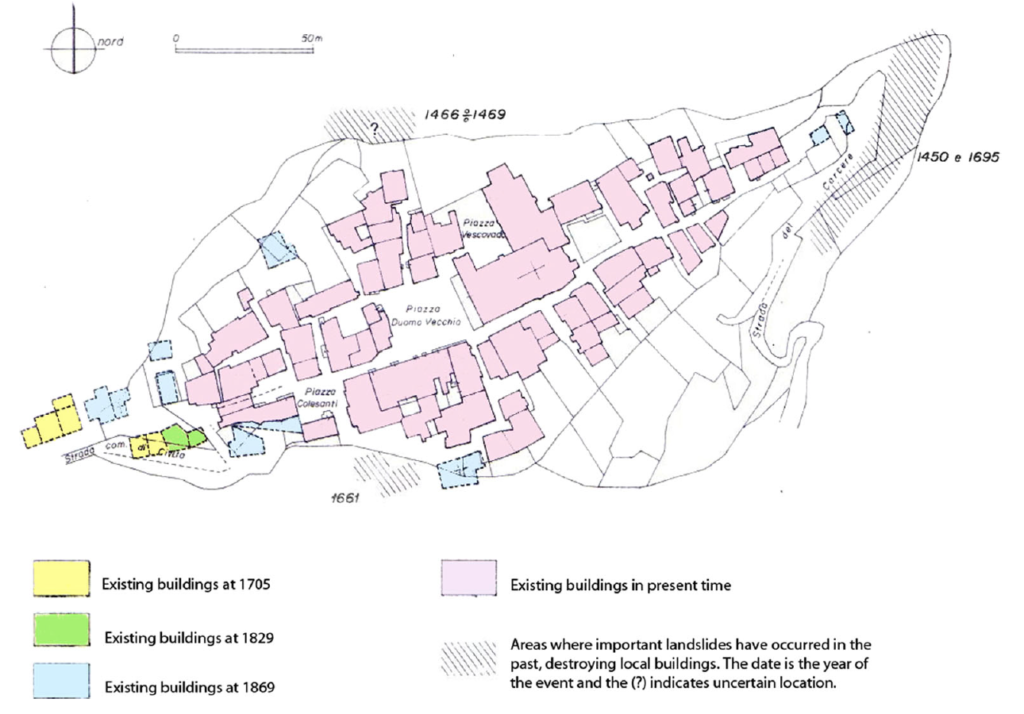

Located in central Italy, about a 100 km north of Rome, the town of Civita dates back to the Etruscan civilization, about 2500 years ago. It was most likely built on top of a hill for military reasons, since the 200 m of difference in height would provide perfect panoramic views. The city’s major development took place during the Middle Ages, and its well-preserved medieval character is one of the features that makes this city so magnificent nowadays. However, in 1695, a terrible earthquake demolished most of Civita by triggering a major landslide below, and forced people to move to the neighbouring village of Bagnoregio. This was not the only landslide that threatened the city. For centuries, Civita has been fighting against the natural degradation of the cliff, with recurring landslides slowly taking down the edges of the plateau, causing some of the medieval buildings to collapse and plummet into the ravine (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution of the upper urbanised area of Civita di Bagnoregio from historical maps, showing many buildings destroyed by landslides during the past centuries. Credit: Margottini, C. & Di Buduo, G. Landslides (2017).

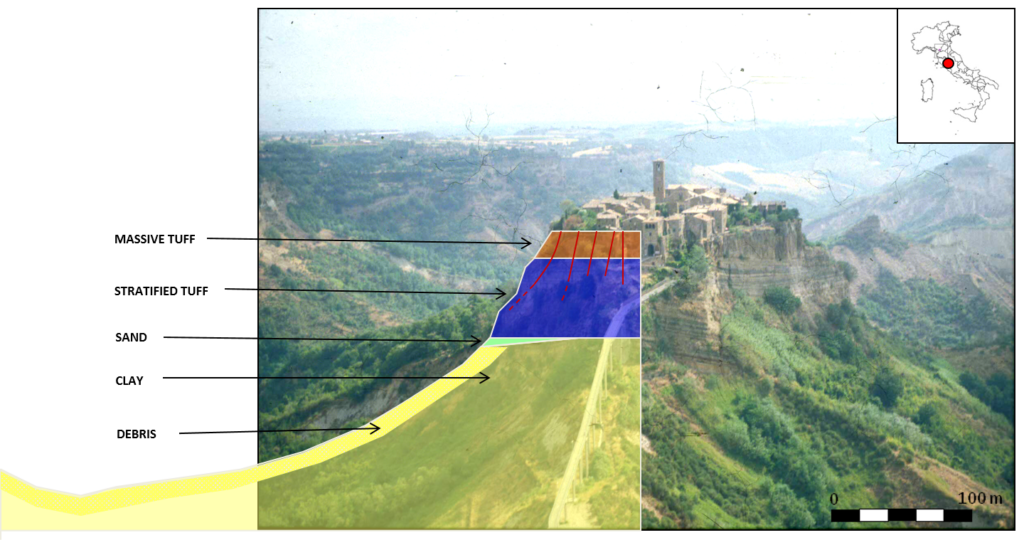

The geology of the plateau explains why this town is so susceptible to landslides (Figure 2, Delmonaco et al., 2004). The top of the plateau consists of a 20 m thick layer of consolidated rock formed from volcanic ash (ignimbrite), also known as tuff. The tuff was deposited by pyroclastic flows (rapid currents of volcanic debris and hot gas) related to the neighbouring Vulsini volcanic complex. This massive tuff layer overlies a more stratified section of pyroclastic deposits, roughly 70 m in thickness. These quaternary volcanic deposits lie above a bedrock of Plio-Pleistocene clay, which can be found all over the valley. This succession forms a classic setting for landslides. In the fragile clay deposits, slope instability is represented by mud flows and debris flows, while the upper, volcanic part of the plateau suffers from rock-falls, toppling and block-slides as it becomes unstable. Landslides can be dated back to 1373 AD, with 150 landslides documented by scientists who investigated the local geomorphology (Margottini and Di Buduo, 2016).

Figure 2. Geological profile of the study area. Credit: Giuseppe Delmonaco.

It seemed that the fate of Civita de Bagnoregio was to slowly disappear, but the city experienced a major turning point in 2013, when mayor Francesco Bigiotti decided to charge an entrance fee for people who wanted to visit the town. Tourists now pay a few euros to cross to the sloping footbridge towards the town. This proved to be a smart move, since people became more attentive and treated the site with more respect. The money raised by the entrance fee partly goes to preserving Civita’s fragile beauty and since 2015, the dying city received the UNESCO World Heritage status. This recognition of cultural heritage now leads to more investments from the regional government in order to preserve the historical site.

If you have the opportunity to visit the Civita, you will first enjoy a magnificent view on the town and the surrounding valley, before descending into the valley to cross the footbridge that provides the only gateway to the town. After a short climb towards the entrance, you’ll pass through an old arc, immediately bringing you back to medieval times. Then, all there is left to do is wander through the charming, quiet streets, observing the beauty of the classical quiet Italian village. Visit the Geology and Landslides museum, have lunch at one of the many authentic restaurants, or walk all the way to the end of the village, away from the other tourists. From there, a small trail leads into the countryside, where you can enjoy the magnificent views on the sharply eroded, clayey ridges in the surrounding badlands valley.

Previously referred to as the dying town, it now seems that there is some hope left after all for Civita di Bagnoregio. Something that will never change, however, is the interplay between mankind trying to survive in a hostile, but strategic environment of immense beauty, and nature that follows its own course of dismantling and eroding the existing relief.

By Elenora van Rijsingen, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Department of Geosciences, France