Buoyancy-driven drones are helping scientists paint a picture of the ocean with sound.

Around the world, silent marine robots are eavesdropping on the ocean and its inhabitants. The robots can travel 1000 metres beneath the surface and cover thousands of kilometres in a single trip, listening in on the ocean as they go.

These bright yellow bots, known as Seagliders, are about the size of a diver, but can explore the ocean for months on end, periodically relaying results to satellites.

Researchers have been utilising gliders for about 20 years, first using them to measure temperature and salinity. But over time, scientists have expanded their capabilities and now they can record ocean sounds.

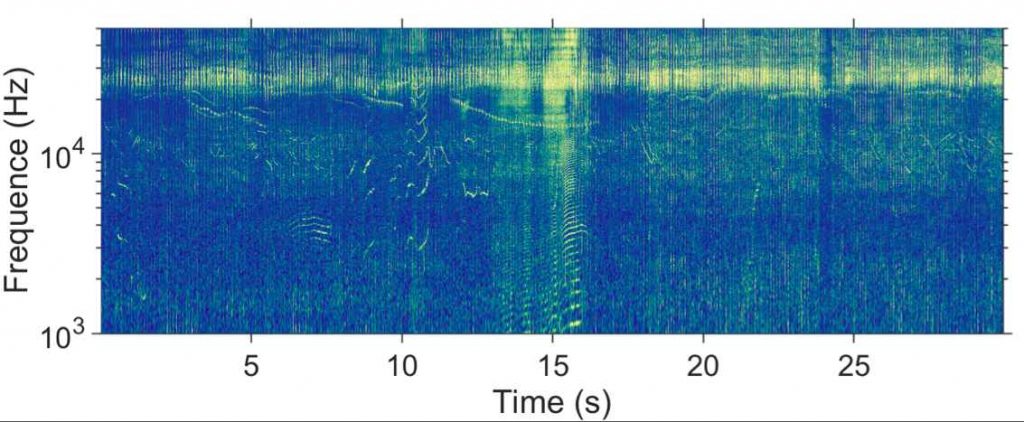

You can learn a lot from the recordings if you know how to read them. The background noise is produced by high winds, the low frequency rumble comes from moving ships, and the punctuating whistles and clicks are produced by different marine species.

Sperm whale and dolphin echolocation clicks. Every two seconds you hear a loud click, the sound of a sperm whale. The more rapid clicks correspond to dolphins. Credit: University of East Anglia

Pierre Cauchy, a PhD researcher from the University of East Anglia, UK, has been using seagliders to create an underwater soundscape across the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Southern Oceans. He presented his latest findings at the EGU General Assembly in Vienna last week.

Here in the ocean, the nights can be noisier than the days. When the sun goes down, fish sing out in chorus, a sound that rings out at 700 Hz. “I wasn’t expecting that, it was serendipitous,” says Cauchy. It’s not only fish that can be picked up by the gliders; dolphins and whales make characteristic whistles and clicks, meaning species can be identified from their vocal patterns alone.

The next step is to cross check the recordings with others made in the area, and confirm which species he’s been listening to. In the future, Cauchy hopes the technology will be used to monitor changes in ecosystem health over time.

While it’s hard to know what a healthy ecosystem sounds like, you can monitor the same spot from year to year and work out whether it is healthier, or less healthy than it was previously. A more healthy ecosystem may be filled with the sounds of different fish, and other species, representing a diverse, species-rich habitat.. A less healthy one would be quiet, or more monotonous.

Pod of long-finned pilot whales in the North Atlantic. Credit: University of East Anglia

The sound of a pod of pilot whales – bright areas indicate bursts of sound at a particular frequency. The patterns and frequencies differ for each species. Credit: Cauchy et al. (2008).

Scientists could also use gliders to fill gaps in our understanding of extreme weather around the world, especially in places where collecting data is a challenge, like the high seas. “That’s the good thing with gliders, you can send them where data is needed,” emphasises Cauchy.

Researchers have been using satellite data to validate wind speed models and map weather events like hurricanes, but even satellites need to be calibrated against measurements made on the Earth’s surface. The seagliders can do just that; hydrophones pick up wind at two to 10 kilohertz and the faster the wind, the louder the sound. “The more in-situ data you have, the better your satellite data is, and that’s better for the models,” Cauchy explains.

Future work could see scientists sending gliders into hurricanes to measure wind speeds reached during extreme weather events.

By Sara Mynott

References

Cauchy, P. Passive Acoustic Monitoring from ocean gliders. EGU General Assembly. 2018.

EGU General Assembly press conference recording available here.