In the glistening waters of Indonesia, shallow corals – the rain forests of the sea – teem with life. Or at least they did once. Towards the end of 2015 the corals started to die, leaving a bleak landscape behind. An international team of researchers investigated the causes of the die-off. Their findings, published recently in the EGU’s open access journal, Biogeosciences, are rather surprising.

Globally, corals face tough times. Increasing ocean-water temperatures (driven by a warming climate) are disrupting the symbiotic relationship between corals and the algae that live on (and in) them.

The algae, known as zooxanthellae, provide a food source for corals and give them their colour. Changing water temperatures and/or levels, the presence of contaminants or overexposure to sunlight, put corals under stress, forcing the algae to leave. If that happens, the corals turn white – they become bleached – and are highly susceptible to disease and death.

Triggered by the 2015-2016 El Niño, water temperatures in many coral reef regions across the globe have risen, causing the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to declare the longest and most widespread coral bleaching event in recorded history. Now into its third year, the mass bleaching event is anticipated to cause major coral die-off in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef for the second consecutive year.

The team of researchers studying the Indonesian corals found that, unlike most corals globally, it’s not rising water temperatures which caused the recent die-off, but rather decreasing sea level.

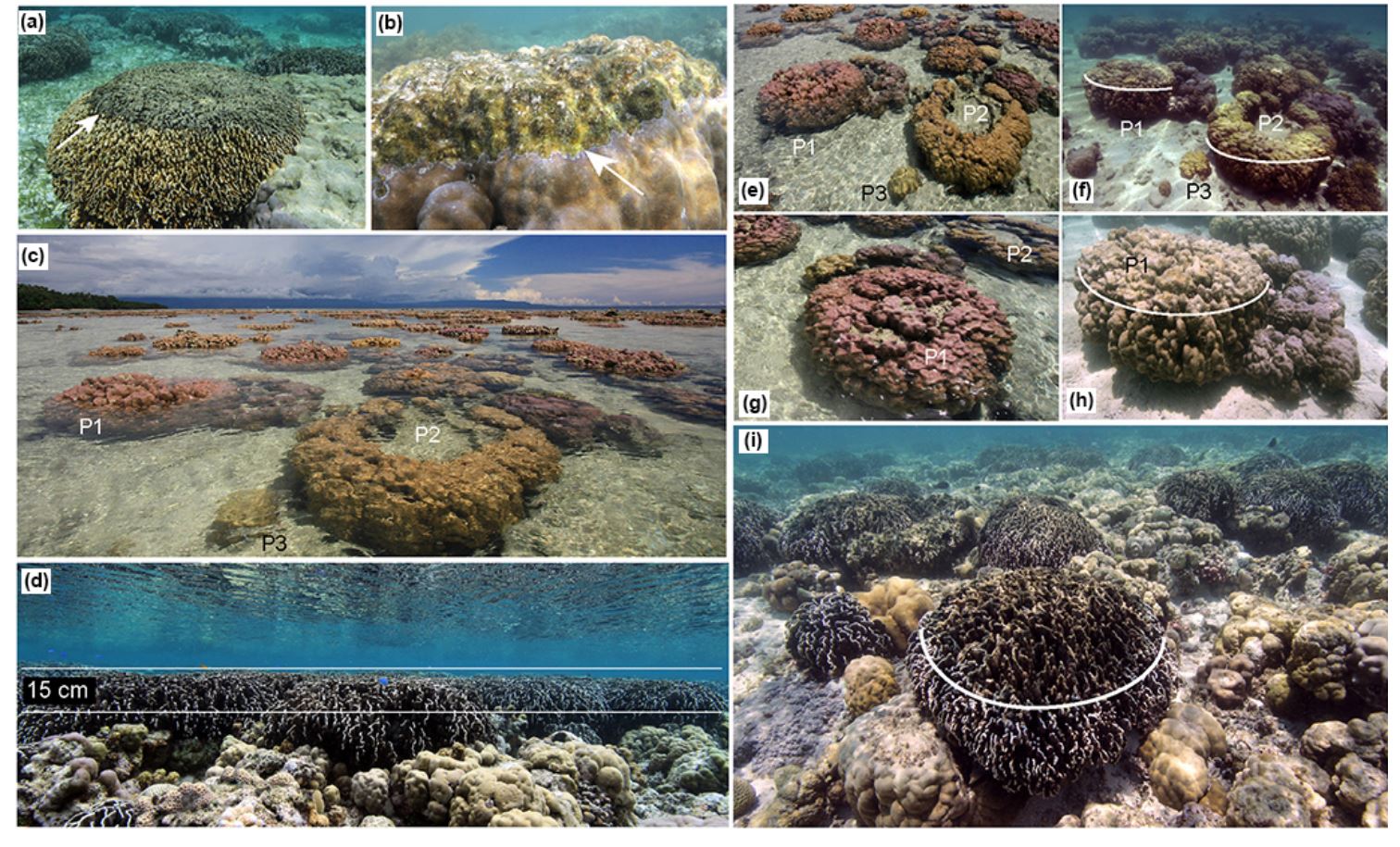

While conducting a census of coral biodiversity in the Bunaken National Park, located in the northwest tip of Sulawesi (Indonesia), in late February 2016, the researchers noticed widespread occurrences of dead massive corals. Similar surveys, carried out in the springs of 2014 and 2015 revealed the corals to be alive and thriving.

In 2016, all the dying corals were found to have a sharp horizontal limit above which dead tissue was present and below which the coral was, seemingly, healthy. Up to 30% of the reef was affected by some degree of die-off.

Bunaken reef flats. (a)Close-up of one Heliopora coerula colony with clear tissue mortality on the upper part of the colonies; (b)same for a Porites lutea colony; (c) reef flat Porites colonies observed at low spring tide in May 2014. Even partially above water a few hours per month in similar conditions, the entire colonies were alive. (d) A living Heliopora coerula (blue coral) community in 2015 in a keep-up position relative to mean low sea level, with almost all the space occupied by corals. In that case, a 15 cm sea level fall will impact most of the reef flat. (e–h) Before–after comparison of coral status for colonies visible in (c). In (e), healthy Poritea lutea (yellow and pink massive corals) reef flat colonies in May 2014, observed at low spring tide. The upper part of colonies is above water, yet healthy; (f) same colonies in February 2016. The white lines visualize tissue mortality limit. Large Porites colonies (P1, P2) at low tide levels in 2014 are affected, while lower colonies (P3) are not. (g) P1 colony in 2014. (h) Viewed from another angle, the P1 colony in February 2016. (i) Reef flat community with scattered Heliopora colonies in February 2016, with tissue mortality and algal turf overgrowth. Taken from E. E. Ampou et al. 2016.

The confinement of the dead tissue to the tops and flanks of the corals, lead the scientists to think that the deaths must be linked to variations in sea level rather than temperature, which would affect the organisms ubiquitously. To confirm the theory the researchers had to establish that there had indeed been fluctuations in sea level across the region between the springs of 2015 and 2016.

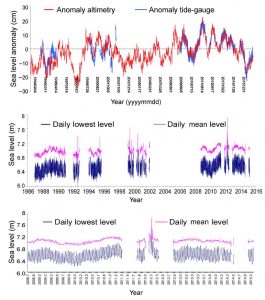

To do so they consulted data from regional tide-gauges. Though not located exactly on Bunaken, they provided a good first-order measure of sea levels over the period of time in question. To bolster their results, the team also used sea level height data acquired by satellites, known as altimetry data, which had sampling points just off Bunaken Island. When compared, the sea level data acquired by the tidal gauges and satellites correlated well.

Sea-level data from the Bitung (east North Sulawesi) tide-gauge, referenced against Bako GPS station. On top, sea level anomalies measured by the Bitung tide-gauge station (low-quality data), and overlaid on altimetry ADT anomaly data for the 1993– 2016 period. Note the gaps in the tide-gauge time series. Middle: Bitung tide-gauge sea level variations (high-quality data, shown here from 1986 till early 2015) with daily mean and daily lowest values. Bottom, a close-up for the 2008–2015 period. Taken from E. E. Ampou et al. 2016.

The data showed that prior to the 2015-2016 El Niño, fluctuations in sea levels could be attributed to the normal ebb and flow of the tides. Crucially, between August and September 2015, they also showed a sharp decrease in sea level: in the region of 15cm (compared to the 1993-2016 mean). Though short-lived (probably a few weeks only), the period was long enough that the corals sustain tissue damage due to exposure to excessive UV light and air.

NOAA provides real-time Sea Surface Temperatures which identify areas at risk for coral bleaching. The Bunaken region was only put on alert in June 2016, long after the coral die-off started, therefore supporting the crucial role sea level fall played in coral mortality in Indonesia.

The link between falling sea level and El Niño events is not limited to Indonesia and the 2015-2016 event. When the researchers studied Absolute Dynamic Topography (ADT) data, which provides a measure of how sea level has change from 1992 to 2016, they found sea level falls matched with El Niño years.

The results of the study highlight that while all eyes are focused on the consequences of rising ocean temperatures and levels triggered by El Niño events, falling sea levels (also triggered by El Niño) could be having a, largely unquantified, harmful effect on corals globally.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer

References and resources

Ampou, E. E., Johan, O., Menkes, C. E., Niño, F., Birol, F., Ouillon, S., and Andréfouët, S.: Coral mortality induced by the 2015–2016 El-Niño in Indonesia: the effect of rapid sea level fall, Biogeosciences, 14, 817-826, doi:10.5194/bg-14-817-2017, 2017

Varotsos, C. A., Tzanis, C. G., and Sarlis, N. V.: On the progress of the 2015–2016 El Niño event, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 2007-2011, doi:10.5194/acp-16-2007-2016, 2016.

What are El Niño and La Niña? – a video explainer by NOAA

Coral Reef Watch Satellite Monitoring by NOAA

Global sea level time series – global estimates of sea level rise based on measurements from satellite radar altimeters (NOAA/NESDIS/STAR, Laboratory for Satellite Altimetry)

El Niño prolongs longest global coral bleaching event – a NOAA News item

NOAA declares third ever global coral bleaching event – a NOAA active weather alert (Oct. 2015)

The 3rd Global Coral Bleaching Event – 2014/2017 – free resources for media and educators

What is coral bleaching? – an infographic by NOAA

The ENSO (El Niño–Southern Oscillation) Blog by Climate.gov (a NOAA resource)

Pingback: Geosciences Column: How El Niño triggere...