Shear zones are areas of intense deformation that localize the movement of one block of the crust with respect to another. In previous posts, we have seen that shear zones contain some very deformed rocks called mylonites, lineations that tell us the direction of movement, and useful kinematic indicators, such as S-C fabrics, that allow geologists to understand which way the rocks moved. However, we have just started to scratch the surface of the complexity of shear zones, which may also contain a special (and very complicated) kind of fold: sheath folds.

What are sheath folds?

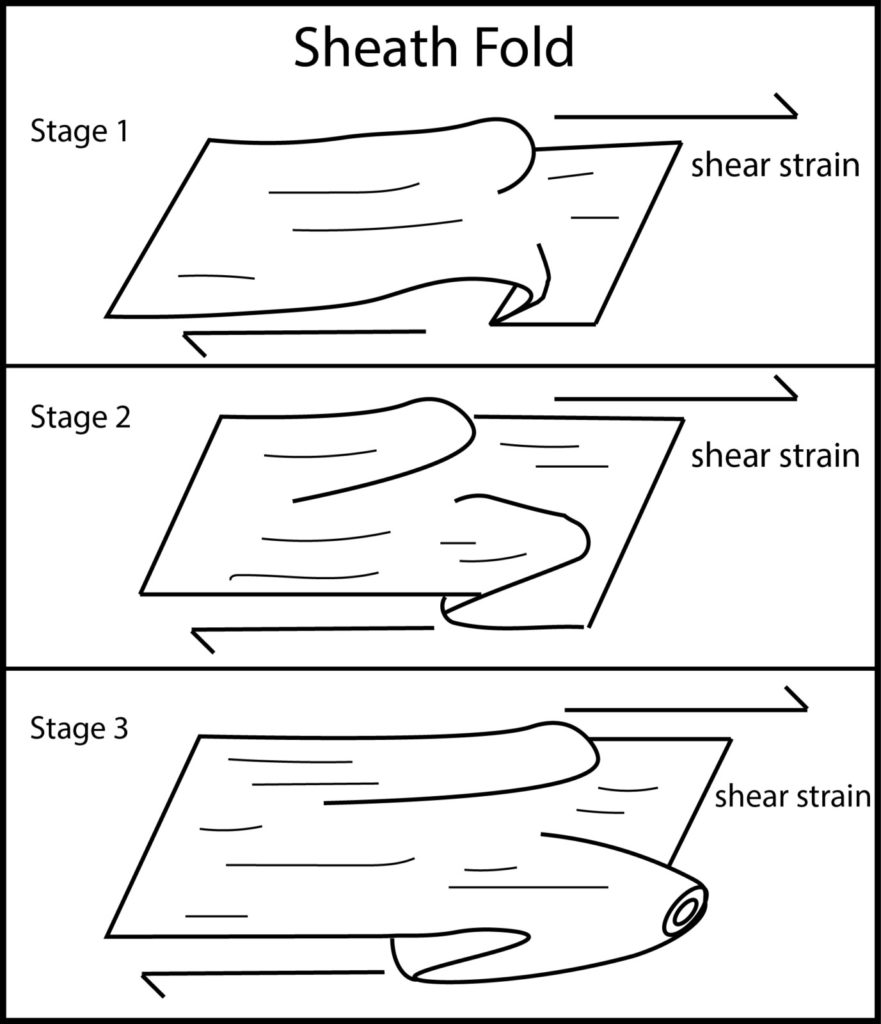

Progressive development of sheath folds in shear zone. Initial asperities on the shear zone margin (stage 1) propagate and become strongly non-cylindrical folds (stage 2) that are tight to isoclinal parallel to the lineation and have closed, curved hinges in cuts perpendicular to it. Sketch by Jeffreyfung (wikimedia.commons).

Imagine holding a piece of fabric, like a curtain, tightly between your hands. If you start to slide your hands past each other, the curtain will slide too but also start to develop irregular folds, as the friction between the cloth and the irregular surface of your hands drags some parts of it more than other. The same happens in rocks. We are used to imagine shear zones as sharp zones of high deformation, but they are commonly irregular, with areas of different thickness and various rock types on their margin. If there is a small irregularity on the shear zone margin, deformation can ‘pinch’ it and drag it with the flow, progressively amplifying it to a strongly irregular fold.

Sheath folds are incredibly irregular. The exact term in geology is ‘non-cylindrical’: they have strongly elongated and curved hinges, like a long nose! In shear zones, they are stretched parallel to the direction of tectonic transport. Due to their complex shape, sheath folds are commonly difficult to visualize. In most outcrops, we ‘see’ only sections through sheath folds. In sections parallel to the direction of transport (i.e. parallel to the stretching lineation), they may look like regular folds, mainly tightly deformed, but with recognizable hinges and limbs.

Folds in mylonitic marble. Looking at this section (parallel to lineation), this might appear as ‘conventional’ right-verging folds. Rio Marina, island of Elba. Photo Samuele Papeschi.

Things become interesting when we look at sections perpendicular to the stretching lineation, because these folds are so strongly sheared and elongated that they form tightly closed surfaces, resembling eyes.

Very flattened fold with a closed outline (behind the coin), formed by folded mylonitic marble layers. Rio Marina, Elba. Photo Samuele Papeschi.

Do you see the outline of the nearly flat fold right behind the coin? Here is another example where I have highlighted the fold:

Easier to see now? If you did not see them at first, do not blame yourself. We spent two entire afternoons on these outcrops trying to understand them. Rio Marina, Elba. Photo Samuele Papeschi.

A strongly non-cylindrical fold is not enough to make a sheath fold!

We now have a list of ingredients for our sheath folds:

- They must be strongly non-cylindrical.

- They develop in shear zones.

- They show a constant orientation of the stretching lineation on their surface, parallel to the sense of tectonic transport.

Point #3 is very important, because there other ways to produce very irregular folds, like folding and refolding (interference folding), but in this case you will get also folded lineations. On the other hand, since sheath folds develop in a shear zone, where rocks are dragged past each other in a specific direction, they show a constantly oriented lineation on their surface, normally perpendicular to the sections where they appear as eyes or ‘flat’ pancakes if you prefer a food analogy. Fold hinges, indeed, tend to be parallel to this lineation.

In this section you can see the closed apical outline of the fold (black dashed line), highlighted by cherty layers in marble. Thanks to erosion you can see the section perpendicular to this fold. Note that cherts there are strongly lineated and that this lineation is constant on the entire outline of the fold. Rio Marina, Elba. Photo Samuele Papeschi.

As you can see, it is not easy to document sheath folds and I needed to look at the same outcrop on all the available sections to describe them. As you might imagine, documenting sheath folds in one shot is very rare, but the spectacular Cap de Creus Shear Zone (Catalunya, Spain) ‘delivers again’, quoting Emily Finch. Here is the most spectacular example of sheath folds you will see today:

Sheath folds in Cap de Creus (Spain). Photo by Dr. Melanie Finch. Quoting her “It’s rare to get a good photo of a sheath fold but Cap de Creus delivers again. These folded quartz veins stick out because they are resistant to weathering. The fold on the right has an extended, conical nose = a sheath fold”

Extras from the EGU community

Sheath folds in very low-grade metamorphic rocks. I will leave this image intentionally non interpreted, just to highlight how difficult it can be to see these folds in most cases. Photo by Subhajit Ghosh. These sheath folds are published here.

References and further reading

Alsop, G. I., & Holdsworth, R. E. (2006). Sheath folds as discriminators of bulk strain type. Journal of Structural Geology, 28(9), 1588-1606.

Alsop, G. I., & Carreras, J. (2007). The structural evolution of sheath folds: A case study from Cap de Creus. Journal of Structural Geology, 29(12), 1915-1930.

Bell, T. H., & Hammond, R. L. (1984). On the internal geometry of mylonite zones. The Journal of Geology, 92(6), 667-686.

Cobbold, P. R., & Quinquis, H. (1980). Development of sheath folds in shear regimes. Journal of structural geology, 2(1-2), 119-126.

Fossen H. (2010). Structural Geology. Cambridge University Press.

Krabbendam, M., & Leslie, A. G. (1996). Folds with vergence opposite to the sense of shear. Journal of Structural Geology, 18(6), 777-781.

Platt, J. P. (1983). Progressive refolding in ductile shear zones. Journal of Structural Geology, 5(6), 619-622.

Tikoff, B., & Greene, D. (1997). Stretching lineations in transpressional shear zones: an example from the Sierra Nevada Batholith, California. Journal of Structural Geology, 19(1), 29-39.

Turner, F. J. & Weiss L. E. (1963). Structural analysis of metamorphic tectonites, Francis J. Turner, Lionel E. Weiss. McGraw-Hill. New York. US.

Domingo Aerden

Thank for this nice review of what sheath folds are and how they are thought to form. Greta photographs also. But I do not think the 3 criteria listed for distinguishing them from fold-interference structures are sufficient: “They must be strongly non-cylindrical” : This can also be due to fold interference – think of dome and basin structures. “They develop in shear zones” Yes, but a shear zone can have pure-shear components and that can cause fefolding of earlier folds. “They show a constant orientation of the stretching lineation on their surface, parallel to the sense of tectonic transport.” A general non-coaxial flow superposed on pre-existing folds will also generate sheath-folds (in the descriptive sense) with constantly oriented stretching lineatinon.

The latter is what was recently proposed for the same sheath folds from Ile de Groix that stood model for the famous experiments of Cobbold & Quinquis (1980) with silicone. You can see our idea in Fig 12 of the article here https://se.copernicus.org/articles/12/971/2021/

Microstructural data are necessary to constrain the kinematics of these structures, apart from field observations.

Cheers, Domingo

Samuele Papeschi

Dear Domingo,

Before I reply, please kindly understand that this blog is divulgative and that I normally try to explain structures avoiding jargon like ‘stress’, ‘strain’, and ‘vorticity’… and surely terms like ‘general shear’, whose use is common only among structural geologists. This considered, the criteria outlined actually allow to distinguish sheath folds from refolded folds, because a sheath fold is a highly non-cylindrical fold formed in zones of high strain (Fossen, 2007), and it has a constant orientation of the stretching lineation over the entire surface of the fold (e.g. Alsop & Carreras, 2007, among many others). This is what allows to distinguish sheath folds from refolded folds, where the lineation is also refolded. So you need to apply the criteria I listed together. Perhaps this was not clear from my post.

A pre-existing fold that is subject to non-coaxial fold and becomes strongly non-cylindrical is still a sheath fold to me, with an interesting origin (rightfully deserving its own paper, as you pointed out – also thank you for sharing!) but still a sheath fold in the descriptive sense, as you said. I simply think that discussing extremes does not help when defining structures in structural geology. The risk is to have definitions that are too complex and practically useless. As structural geologists, we love structural complexity and we love to document extreme cases, but – again – this is too much for the aims of this blog.

Cheers,

Samuele

Domingo Aerden

Dear Samuele, sorry if my comment was too technical. I agree that there is nothing wrong with using the term ‘sheath fold’ in the descriptive/geometric sense. The point I was trying to make is that the 3 criteria you listed are not sufficient to distinguish between simple shear (as shown in your sketch) vs more complex scenarios involving pure shear or polyphase deformation. I make up form your comment that we agree on this too, as Alsop (2006). In my experience, though, most (structural) geologists assumed the simple-shear model of your sketch, whereas later microstructural analysis indicated a more complex (polyphase) origin. Cheers, Domingo

Samuele Papeschi

Dear Domingo, do not worry. I am not assuming simple shear models, but I need to simplify things a little bit for a wider public. In any case, I think that the complex scenarios you are pointing out are not easy to identify in the field, they require careful analysis of microstructures/vorticity analysis. I do not think, we can improve (much) these criteria to avoid this complexity, but if you have any suggestions I would be glad to update the blog.

Cheers,

Samuele

Samuele Papeschi

P.S: If possible, please provide a list of criteria that in your opinion are sufficient to describe sheath folds and I will update the blog post

Matthew J. Rhoades, CPG, RG

Exceptional post with great, detailed photos to explain the kinematics. Please keep these coming!

Samuele Papeschi

Thank you, Matthew!

C Bhushan

I loved the post and enjoyed reading it.

I am working in field and encounter such things in my daily field work.

This post definitely helps me in understanding my area in.much more efficient way.

I would appreciate if something on core interpration can be put up…like interpration of various structures in a drill core.

Regards

Samuele Papeschi

Thank you very much!

I personally do not think I can write something about drill core interpretations, as I have never done anything like that in my life.

However, we are currently recruiting new people for this series, so hopefully someone skilled in that will show up and I may ask them!

Cheers,

Samuele

Angie Windhauser

I am not an expert, common citizen in drill core interpretation;

but, I have worked with many Geologists.

Shear strain, will always show up on a drill core sample in the target area of tension.

However, while the core shows normal settled and defined trends, crustatious; it may also show chipping from forced, unnatural intrusions that can shift the level of an active strain from low to high.