Crew in hardhats and red safety gear bustle about, preparing our ship for departure. A whale spouts nearby in the Straits of Magellan, a fluke waving in brief salute, before it submerges again. Our international team of 29 scientists and 2 science communicators, led by co-Chief Scientists Mike Weber and Maureen Raymo, is boarding the JOIDES Resolution, a scientific drilling ship. We’re about to journey on this impressive research vessel into Antarctic waters known as Iceberg Alley for two months on Expedition 382 of the International Ocean Discovery Program.

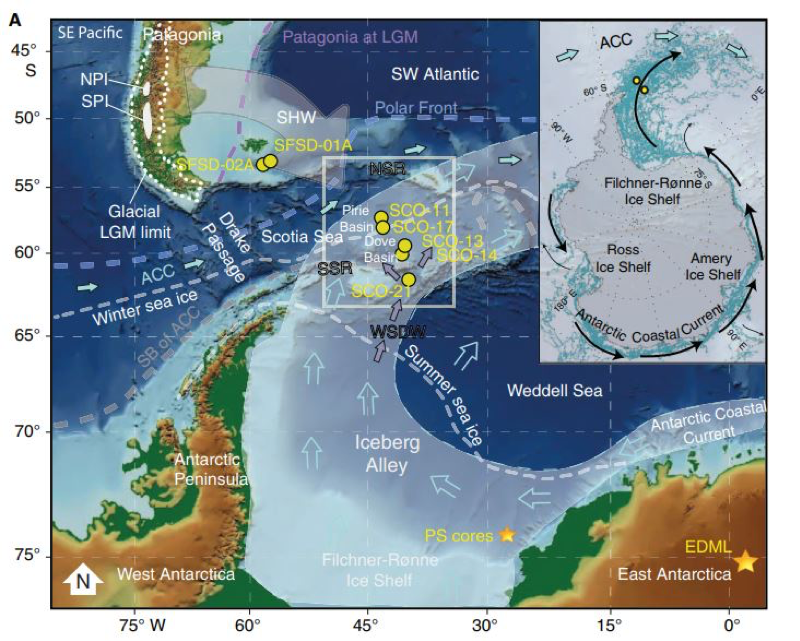

Not only are these some of the roughest seas on the planet, it is also where most Antarctic icebergs meet their ultimate fate, melting in the warmer waters of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), which races unimpeded around the vast continent. And there, in the Scotia Sea, we will drill deep into the sea floor to learn more about the history of the Antarctic Ice Sheet.

The Drilling Ship

The JOIDES Resolution is a 134-meter-long research vessel topped by a derrick towering 62 meters above the water line. It can drill hundreds of meters into the sea floor to retrieve long cylinders of mud called cores. Analyzing this sediment can tell scientists much about geology and Earth’s history, including the history of Climate Change.

“Sediment cores are like sedimentary tape recorders of Earth’s history,” says Maureen Raymo. “You can see how the climate has changed, how the plants have changed, how the temperatures have changed. Imagine you had a multilayer cake and a big straw, and you just stuck your straw into your cake and pulled it out. And that’s essentially what we do on the ocean floor.”

Our expedition is “going to a place that’s never really been studied before,” adds Maureen Raymo. “In fact, we don’t even know what the age of the sediment at the bottom will be.” Nevertheless, we hope to retrieve a few million years’ worth of sediment, perhaps even more. The sediment cores will provide a nearly continuous history of changes in melting of the Antarctic Ice Sheet.

What can these cores tell us?

As icebergs melt, the dust, dirt, and rocks they carry—known as “iceberg rafted debris”—fall down through the ocean and are deposited as sediment on the seafloor. Analyzing this sediment can tell us when the icebergs that deposited it calved from the ice sheet, and even where they came from. At times when more debris was deposited, we know more icebergs were breaking away from the Antarctic Ice Sheet, which tells us the ice sheet was less stable.

Much shorter cores previously collected at our drilling sites reveal high sedimentation rates, allowing us to observe changes in the ice sheet and the climate on short timescales (from just tens to hundreds of years).

We now know that rapid discharge of icebergs—caused by rapid melting of Antarctic ice shelves and glaciers—occurred in the past, and that episodes of massive iceberg discharge can happen abruptly, within decades. This has huge implications for how the Antarctic Ice Sheet may behave in the future as our world warms.

Where do icebergs come from?

Ok, let’s back up a little—back to where these icebergs were born. Icebergs break off or “calve” from the margins (edges) of ice shelves and glaciers. Ice shelves are floating sheets of ice around the edges of the land. They are important because they have a “buttressing” effect—that is, they act as a wall, holding back the ice behind them. Glaciers are great flowing rivers of ice that grind their way across the land, picking up the rocks and dirt that become iceberg-rafted debris.

Thwaites velocity map animation [Credit: Kevin Pluck, Pixel Movers & Maker]

Most Antarctic icebergs travel anti-clockwise around Antarctica and converge in the Weddell Sea, then drifting northward into the warmer waters of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

Iceberg flux 1976-2017 [Credit: Kevin Pluck & Marlo Garnsworthy, Pixel Movers & Makers]

As our planet warms due to our greenhouse gas emissions, warmer ocean currents are melting Antarctica’s massive glaciers from below, thinning, weakening, and destabilizing them. In fact, the rate of Antarctic ice mass loss has tripled over the last decade alone.

Polar researchers predict that global sea level will rise up to one meter (around 3.2 feet) by the end of this century, and most of this will be due to melting in Antarctica. And if vulnerable glaciers melt, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is more likely to collapse, raising sea level even further.

A Hazardous Voyage

We face several hazards on this journey. We are hoping we won’t encounter sea ice, as our vessel is not ice-class, but it’s something we must watch for, especially later in the cruise as winter draws nearer. It is certain that, at times, we’ll experience a sea state not conducive to coring—or to doing much but swallowing sea-sickness medication and retiring to one’s bunk. In heave greater than 4–6 meters, operations must stop for the safety of the crew and equipment.

Of course, our highly experienced ice observer will be ever on the lookout for our greatest hazard—icebergs, of course! We are likely to encounter everything from very small “growlers” to larger “bergy bits” to massive tabular bergs. In fact, it is the smaller icebergs that present the most danger to the ship, as large icebergs are both visible to the eye and are tracked by radar, while smaller ones can be more difficult to detect, especially at night. Nevertheless, we are intentionally sailing into the area of highest iceberg concentration and melt.

“My hope,” says Mike Weber, “is that our expedition will unravel the mysteries of Antarctic ice-sheet dynamics for the past, and this may tell is something about its course in the near future.”

Edited by Sophie Berger

The JOIDES Resolution is part of the International Ocean Discovery Program and is funded by the US National Science Foundation.

Marlo Garnsworthy is an author/illustrator, editor, science communicator, and Education and Outreach Officer for JOIDES Resolution Expedition 382 and previously NBP 17-02. She and Kevin Pluck are co-founders of science communication venture PixelMoversAndMakers.com, creator of the animations in this article.

Marlo Garnsworthy is an author/illustrator, editor, science communicator, and Education and Outreach Officer for JOIDES Resolution Expedition 382 and previously NBP 17-02. She and Kevin Pluck are co-founders of science communication venture PixelMoversAndMakers.com, creator of the animations in this article.

![Image of the Week – Seven weeks in Antarctica [and how to study its surface mass balance]](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2019/02/Vue_globale-161x141.jpg)