Dr Melanie Windridge, a physicist and mountaineer, successfully summited Mount Everest earlier this year and has been working on an outreach programme to encourage young people’s interest in science and technology. Read about her summit climb, extreme temperatures, and the science supporting high-altitude mountaineering in our Image of the Week.

It’s bigger than it looks! Experiencing the majesty of Everest

In April/May this year I climbed Mount Everest. To the top. It was two months of patient toil but in surroundings so majestic, impressive and inspiring. The Western Cwm (an amphitheatre-like valley shaped by glacial erosion) is vast, the summit ridge is steep and Khumbu Glacier was fascinating in itself. Our base camp was on the glacier and it changed daily in subtle ways – the ice melted, the rocks moved, the paths morphed. And the icefall was slightly different each time I passed through – the route changing through a collapsed area, a crevasse widening, or the rope buried by ice-block debris fallen from above. It’s a wonderful, interesting place and I am grateful to have experienced it. You can read more about the climb on my personal blog.

Fig.2: The view up the Western Cwm from Camp 1. Lhotse can be seen in the distance and the summit of Everest mid-left. [Credit: Melanie Windridge].

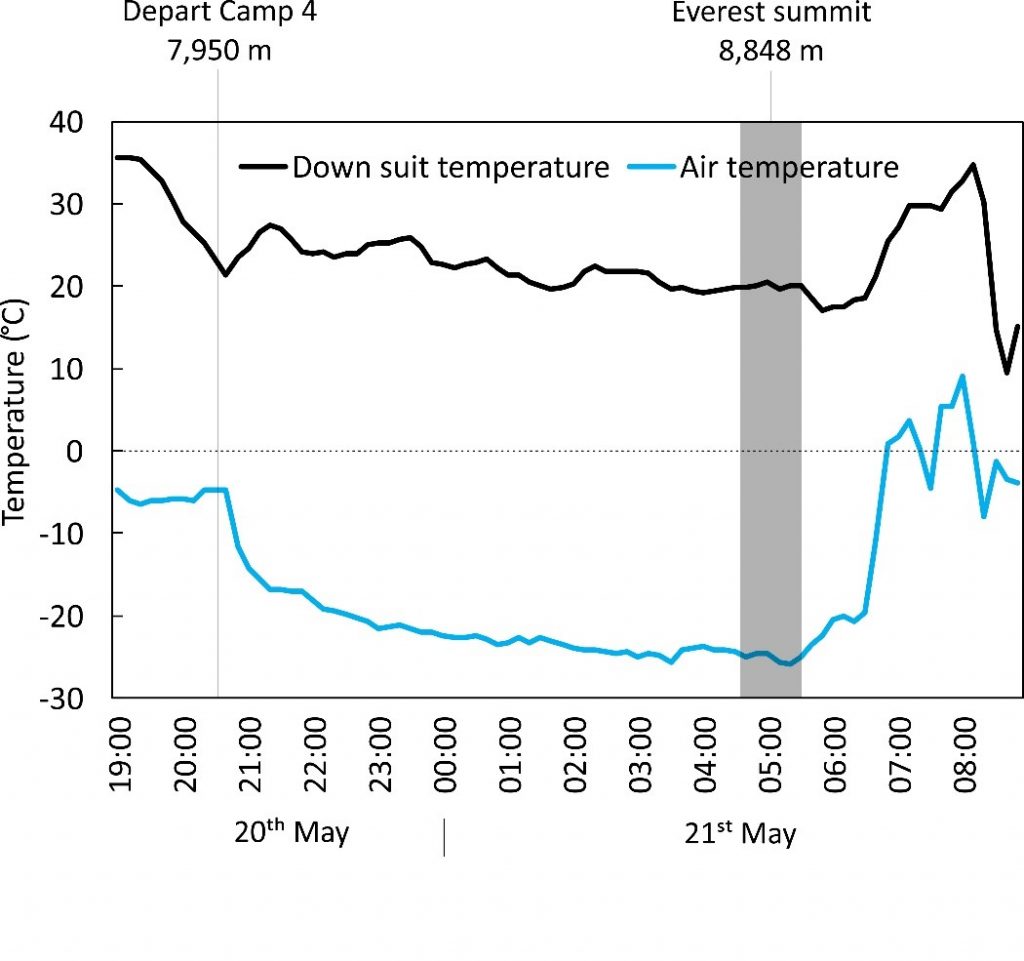

Everest, of course, is extreme. It is steep almost everywhere, so you barely get a let-up anywhere beyond the Western Cwm. The temperature differences are extreme too – it is extremely hot or extremely cold. I took a couple of temperature loggers with me to the summit (one in a base-layer pocket under my down suit and one in an outer pocket of my rucksack). You can see from the graph of summit night (the climb from Camp 4 to the summit of Everest) (Fig. 3) how the temperature varied by tens of degrees. Since climbers dress for the coldest temperatures, this can be quite uncomfortable when the sun comes out. The temperature on summit night got down to about -25°C, but during the day it rose to 10 degrees or more so that we were sweating into our down suits.

Fig.3: Graph showing the readings from two separate temperature loggers on summit night – one in a base-layer pocket under the down suit (Down suit temperature) and one in an outer pocket of the rucksack (Air temperature). The temperature rises quickly after sunrise, which was experienced on the summit [Credit: Melanie Windridge and Scott Watson].

Sharing the Science of the Summit

It was science that really got me interested in Everest, when I realised that the main reason the British had succeeded in 1953 but hadn’t in the 1920s and 30s was because of scientific understanding and the state of technology. But so often we don’t talk about the science that supports us in these great endeavours; instead we put it all down to the strength of the human spirit. I think we need to talk about both.

As part of my climb, I have been working on an outreach project to highlight how science and technology have improved safety and performance on Everest. I have made Science of Everest videos for the Institute of Physics YouTube channel and will be giving public talks. I wanted to show how science supports us and what has improved in recent decades to contribute to the falling death rate on Everest.

In the video series I look at changes in weather forecasting, communications, oxygen, medicine and clothing. We also consider risk and preparation – videos that went out before I left for Everest – because, as a scientist, I looked into past data to see how I could give myself the best chance of reaching the summit and returning safely.

Communication has improved not only because we have a greater variety than was available to the first ascentionists or the early commercial climbers (we have satellite phones, mobile/cell-phones and WiFi now), but also because everything is a lot smaller. Electronic components have greatly reduced in size so that radios used on the mountain now are small and handheld in comparison to the bulky sets of the 1950s (see video above).

Of course, the implication of the project is wider than just Everest. I am interested in the importance of science and exploration in general. For me, Everest is an icon of exploration – the way that human curiosity, ingenuity, determination and endurance come together to drive us forward. Reaching into the unknown is good for us, on a societal level and on a personal level. I hope to give an appreciation of the value of science in our lives, give students an insight into interesting careers that use science, and show the value of doing things that scare us!

Further reading

- Image of the Week – Inspiring Girls

- Image of the Week – Far-reaching implications of Everest’s thinning glaciers

- Image of the Week – Supraglacial debris variations in space and time!

Edited by Scott Watson and Clara Burgard

Dr Melanie Windridge is a physicist, speaker, writer… with a taste for adventure. She is Communications Consultant for fusion start-up Tokamak Energy, author of “Aurora: In Search of the Northern Lights” and is currently working on a book about Mount Everest.

Dr Melanie Windridge is a physicist, speaker, writer… with a taste for adventure. She is Communications Consultant for fusion start-up Tokamak Energy, author of “Aurora: In Search of the Northern Lights” and is currently working on a book about Mount Everest.

Website: www.melaniewindridge.co.uk (see the Science & Exploration blog to read about the Everest climb)

Twitter @m_windridge, Facebook /DrMelanieWindridge, Instagram @m_windridge

Science of Everest videos on the Institute of Physics YouTube channel http://bit.ly/EverestVids