How water travels through and beneath the interior of debris-covered glaciers is poorly understood, partly because it can be difficult to access these glaciers at all, never mind explore their interiors. In this Image of the Week, find out how these aspects can be investigated by drilling holes all the way through the ice…

Hydrological features of debris-covered glaciers

Debris-covered glaciers can have a range of hydrological features that do not usually appear on clean-ice valley glaciers, such as surface (supraglacial) ponds. These features are produced as a result of the variable melting that occurs across the glacier surface, depending on the thickness of the debris layer on the surface. Melting is reduced where the debris layer is thick (e.g. near the terminus), which leads to mass loss primarily by thinning, rather than terminus retreat like clean-ice glaciers (read more about this process in this previous blog post). This produces a low-gradient surface covered by hummocks and depressions in which ponds can form, often with steep bare ice faces (ice cliffs) surrounding them. The occurrence of ice cliffs and ponds also affects the surface melt rate, as glacier ice in/on/under these features melts considerably faster (up to 10 and 7 times more, respectively) than that of the debris-covered areas surrounding them (Sakai et al., 2000). Consequently, these hydrological features are an important contributing factor to the general trend of surface lowering of debris-covered glaciers (Bolch et al., 2012).

As a result, most hydrological research on debris-covered glaciers to date has focused on the (more accessible) supraglacial hydrological environment, as well as measuring the proglacial discharge of meltwater from these glaciers, which is a vital water resource for millions of people (Pritchard, 2017). Below the debris-covered surface of these glaciers, next-to-nothing is known about their hydrology; do drainage networks exist within (englacial) or beneath (subglacial) these glaciers, can they exist, and how can they be observed in such challenging environments?

A limited amount of direct research has been carried out in attempt to answer some of these questions, such as speleological techniques to investigate shallow englacial systems on a few glaciers (e.g. Gulley and Benn, 2007; Narama et al., 2017). However, all other inferences of subsurface drainage through debris-covered glaciers have come from hydrogeochemical analyses of water samples taken from the proglacial environment (e.g. Hasnain and Thayyen, 1994) or interpretation of observed glacier dynamics from satellite imagery (e.g. Quincey et al., 2009). While relict englacial features can be observed on the surface of many debris-covered glaciers (Figure 2), studying these systems while they are still active is more difficult.

Fig. 2: A relict englacial feature in the centre of an ice cliff on Khumbu Glacier (looking downglacier), through which the associated supraglacial pond is thought to have drained in the past. Following the drainage event, the pond water-level would have dropped, exposing the ice cliffs around its edge and resulting in the pond water-level being too low to sustain a water flow through the channel. The inset shows the same feature from the far side (looking upglacier): on this side, a vast amount of surface lowering of the ice surface has occurred and the previously englacial channel is now visible from the surface. For scale, the feature is approximately 10 metres in height. [Large image credit: Evan Miles; Inset image credit: Katie Miles]

Hot-water drilling to investigate subsurface hydrology

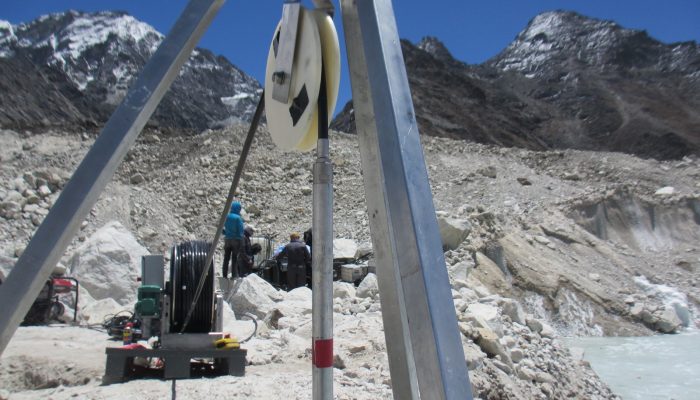

One way in which potential hydrological systems beneath the surface of debris-covered glaciers can be investigated is through the use of hot-water drilling, as was carried out on Khumbu Glacier, Nepal Himalaya this year by the EverDrill team. A converted car pressure-washer was used to produce a small jet of hot, pressurised water, which was sent through a spool of hose into the drill stem to melt the ice below as it was slowly lowered into the glacier (our Image of the Week). The result (if all went well!) was a borehole 10-15 cm in width, that penetrated the ice all the way to the glacier bed (Figure 3). During the field campaign, we managed to drill 13 boreholes at 3 different drill sites across Khumbu Glacier, ranging in length from 12 to 155 metres.

Once the borehole has been drilled, it can be used to investigate the hydrology of the glacier in a number of ways. If the water level suddenly drops while drilling is in progress, it is possible that the borehole has cut through an englacial conduit, through which the excess drill water has drained. If it drops at the base of a borehole drilled to the bed, it can be assumed that some form of subglacial drainage network exists at the base of the glacier, and the excess water drained through this system. Such features can be examined further through the use of an optical televiewer (360° camera that is lowered slowly through the length of the borehole, taking hundreds of images to give a complete picture of the internal surface of the borehole), or by installing a variety of sensors along the hole’s length to collect various types of data.

Fig. 3: A borehole drilled into Khumbu Glacier during the EverDrill field season in Spring 2017. The borehole was approximately 10 cm in width. A small channel (to the left of the borehole) was formed during the drilling process to drain away the excess water as the borehole was drilled. [Credit: Katie Miles]

During the EverDrill fieldwork in Spring 2017, we televiewed three of the drilled boreholes. These boreholes were then instrumented with sensors to measure the temperature of the ice and, where the boreholes reached the bed, a subglacial probe to measure electrical conductivity, temperature, water pressure and suspended sediment concentration (turbidity). We have left these probes in the boreholes, so that we have measurements both through our field season and additionally through the monsoon summer months. This will allow us to see whether any subsurface hydrological drainage systems develop when there is an additional source of water contributing to the melting of these glaciers. We will return in October to collect this data, and hopefully find out a little more about the englacial and subglacial drainage systems of this debris-covered glacier!

Further reading

- Bolch, T. et al. (2012): The State and Fate of Himalayan Glaciers. Science, 336(6079), pp.310–314., doi: 10.1126/science.1215828.

- Gulley, J. & Benn, D.I. (2007): Structural control of englacial drainage systems in Himalayan debris-covered glaciers. Journal of Glaciology 53(182), pp.399–412.

- Hasnain, S.I. & Thayyen, R.J. (1994): Hydrograph separation of bulk meltwaters of Dokriani Bamak glacier basin, based on electrical conductivity. Current Science, 67(3), pp.189–193.

- Narama, C. et al. (2017): Seasonal drainage of supraglacial lakes on debris-covered glaciers in the Tien Shan Mountains, Central Asia. Geomorphology, 246, pp.133-142. doi.:10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.03.002.

- Pritchard, H.D. (2017): Asia’s glaciers are a regionally important buffer against drought. Nature, 545(7653), pp.169–174, doi:10.1038/nature22062.

- Quincey, D.J. et al. (2009): Ice velocity and climate variations for Baltoro Glacier, Pakistan. Journal of Glaciology, 55(194), pp.1061–1071.

- Sakai, A. et al. (2000): Role of supraglacial ponds in the ablation process of a debris-covered glacier in the Nepal Himalayas. In M. Nakawo, C. F. Raymond, & A. Fountain, eds. Debris-Covered Glaciers. Oxford: International Association of Hydrological Sciences, pp. 119–130.

- Image of the Week – Supraglacial debris variations in space and time!

- Image of the Week – Hidden Beauty on a Himalayan Glacier

- Image of the Week – Far-reaching implications of Everest’s thinning glaciers

Edited by Morgan Gibson, Clara Burgard and Emma Smith

Katie Miles is a PhD student in the Centre for Glaciology, Aberystwyth University, UK, studying the internal structure and subsurface hydrology of high-elevation debris-covered glaciers in the Himalaya by investigating boreholes and measurements that can be made within them. She is also interested in the potential of Sentinel-1 SAR imagery in detecting lakes on the surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Katie tweets at @Katie_Miles_851, contact email: kam64@aber.ac.uk

Katie Miles is a PhD student in the Centre for Glaciology, Aberystwyth University, UK, studying the internal structure and subsurface hydrology of high-elevation debris-covered glaciers in the Himalaya by investigating boreholes and measurements that can be made within them. She is also interested in the potential of Sentinel-1 SAR imagery in detecting lakes on the surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Katie tweets at @Katie_Miles_851, contact email: kam64@aber.ac.uk

Magic Himalaya

wow its nice about the Magic Himalayan glacier.

those are danger for trekking. we have khambu glacier in Nepal where we can walk and cross. The Everest base camp is on khambu glacier. Everest base camp trek is like by many people.