Today’s image of the week comes from stunning setting of Chhota Shigri Glacier in the Pir Panjal Range of northern India. The range is part of the Hindu-Kush Karakorum Himalaya region which is a notoriously challenging place to work as it is very remote and completely inaccessible during the winter months. However, when have these challenges ever stopped a hardy glaciologist?!

Our image this week was taken during a field expedition as part of an ongoing long term monitoring program in the area and today we are going to tell you why the region is so important (other than being the source of some rather good photos!)

Why is monitoring glaciers in the Himalaya so important?

Location of Chhota Shigri Glacier taken from Wagon et al., 2007

The Hindu-Kush Karakorum Himalaya region is made up of the biggest mountain ranges on Earth which contain the largest ice mass outside of the polar regions. This region provides water to 50-60% of the world’s population (Wagon et al., 2007), some of which comes from glacial melt water, therefore it is critical to understand how the glaciers in this region may respond to ongoing climate change and predict the impact this may have for the future. As glaciers are very sensitive to changing climate they are also used to understand climate variations at annual and decadal timescales in the region.

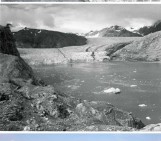

Chhota Shigri Glacier is representative of many glaciers in this region and was chosen as the site for a long-term monitoring program in 2002. It was chosen for a number of reasons including previous field studies on the glacier in the 1980s, glacier geometry, accessibility and its dynamic environment; with areas of partial debris cover and supraglacial lakes (as seen in the image above). The data record on this glacier now continuously spans 13 years and the program has become a benchmark for studying Himalayan glaciers.

What do we see on the picture

The beautiful shot shows a supraglacial lake, a pond of liquid water, on the top of the Chhota Shigri Glacier. This supraglacial lake is an ephemeral lake, forming immediately after winter season. Supraglacial lakes form due to the melting of snow/ice and their presence helps to determine surface melt rates. When the lake water drains it also allows the distribution of subsurface hydrological conduits to be investigated. If the lake does not drain and exists long term there may be glacial lake outburst floods. These are a natural hazard and must be monitored and better understood. This is just one of the aspects of Chhota Shigri Glacier that is being investigated by the long term monitoring program.

Chhota Shigri Glacier has the longest monitoring record

The long term monitoring program, initiated on Chhota Shigri Glacier in 2002, has recorded the evolution of mass balance, ice velocity, ice thickness, stream runoff and melt water quality. The program is a joint collaboration between India and France under the frame work of DST/CEFIPRA programme at School of Environmental Science, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Presently, the annual and seasonal mass balance series (13 years) of Chhota Shigri glacier since 2002 is the longest continuous record in the entire Hindu-Kush Karakorum Himalaya region and represents a benchmark for climate change studies in this region. To measure the annual and seasonal mass balance, we survey the glacier at the end of winter season (May/June) for winter balance measurements and end of summer (September end/October) for annual measurements. We monitor a network of ablation stakes distributed throughout the entire ablation zone (including debris-covered area) to estimate the glacier-wide ablation. To estimate the accumulation we drill snow cores or dig snow pits at representative locations within the accumulation zone (>5150 m) of Chhota Shigri Glacier. For more detailed information and the results of this monitoring see Azam et al. (2016) and Ramanathan (2012).

Long term monitoring on Chhota Shigri Glacier (a) accumulation zone at the end of summer (area is largely covered in dust with clearly visible medial moraine . (b) accumulation zone at the end of winter (fresh snow cover). (c) ablation stake (bamboo) installation in a partly debris covered region during the summe. (d) drilling of snow core at top of the glacier during winter (Credit: Arindan Mandal).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India, SAC-ISRO, CEFIPRA, INDICE, GLACINDIA and CHARIS for funding our research. Special thanks to Emma and Sophie for help in putting together this post.

Edited by Emma Smith and Sophie Berger

Arindan Mandal is a PhD student at the School of Environmental Science, Jawaharlal Nehru university, New Delhi, India under the supervision of Prof. AL. Ramanathan. His current work is focused on Chhota Shigri Glacier where he is working to analyse the past and present state of mass balance in the changing climate scenario and also to understand the complex local scale meteorological processes that drive the mass balance of the glacier. He is working to develop a coupled distributed surface energy-balance model combined with various glaciological and hydrological aspect using in-situ dataset to understand the processes that govern and runoff at Chhota Shigri glacier pro-glacial stream and its sensitivity to the future climate. He tweets as @141Arindan.

Arindan Mandal is a PhD student at the School of Environmental Science, Jawaharlal Nehru university, New Delhi, India under the supervision of Prof. AL. Ramanathan. His current work is focused on Chhota Shigri Glacier where he is working to analyse the past and present state of mass balance in the changing climate scenario and also to understand the complex local scale meteorological processes that drive the mass balance of the glacier. He is working to develop a coupled distributed surface energy-balance model combined with various glaciological and hydrological aspect using in-situ dataset to understand the processes that govern and runoff at Chhota Shigri glacier pro-glacial stream and its sensitivity to the future climate. He tweets as @141Arindan.

Contact Email: arindan.141@gmail.com,

Simon

Nice article! Just a comment: it is excessive to state that “Meltwater from this ice provides water to 50-60% of the world’s population”. In the cited paper (Wagnon et al 2007) it is actually written that “the HKH region provides water to 50–60% of the world’s population”. Most of the runoff comes from snowmelt and rainfall, although icemelt is important during the dry season.

Emma C. Smith

Hello Simon,

Thank you for clarifying this, we have amended the article as such.

Many thanks,

Emma

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week – Supraglacial debris variations in space and time!

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week – Making waves: assessing supraglacial water storage for debris-covered glaciers