Hi Larissa, thankyou for spending time with us today! To break the ice, could you tell us a little about yourself and your research?

Ha, I see what you did there. I’m Larissa, she/her, 29, and a PhD candidate at the Institute of Hydrology and Water Resources Management in Hannover, Germany.

I’ve been fascinated by snow and ice since I was little, writing my first ever school report and then later my bachelor thesis on avalanches. The latter was a little more advanced though! Being a snowboard instructor and writing that thesis is what actually convinced me that I could merge my passion for science and snow, which brought me to glacier modelling. After my master’s degree in Climate Change at University College London, I started a PhD at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research in Utrecht, working on Greenland Ice Sheet Modelling with CISM. After severe health problems I had to quit that project, and thought I was done with science. I figured it wasn’t meant to be, and moved to Iceland as an artist. However, glaciology called me back. Through coincidence and luck, I ended up in Hannover, where I’m now in my final year of the project GLISSADE: glacier mass balance modelling on seasonal and decadal scales. I work with the Open Global Glacier Model (OGGM), which has an incredible open source community. My work focuses on improving the predictability of mass balance on relatively short timescales. With glaciers as important, but diminishing, water storage vessels, this is becoming increasingly important for water resource management.

The media surrounding the recent COP26 presented a bleak narrative of Earth’s future climate, with an ice-free planet and swollen sea levels; researchers even named a receding Antarctic glacier “Glasgow” in a stark reminder of what’s at stake. When predicting future changes scientist often look to the past. As a glaciologist working with climate change, could you explain why investigating the past is useful, or needed, when researching the future of glaciers?

As much as glaciers themselves change over time, the way they respond to changes in climate remains fundamentally the same. To estimate how and in what timeframe certain glacier states are reached, we need to look at markers of former glaciation and the climate characteristics back then, and compare them to the present day. When we can say with confidence how glaciers formerly responded to certain shifts in climate, this knowledge can be applied to the prediction of glacier states under future climate scenarios. The situations we might have to prepare for, we haven’t yet seen in our lifetime, but we can imagine and predict them from the past.

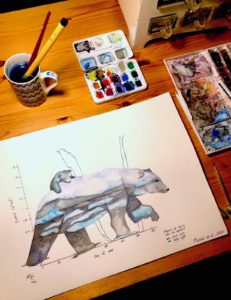

You’re also a talented artist, working with watercolours to communicate climate science to a broad audience. Do you think reaching the public through other mediums – such as art – is important for keeping non-experts engaged?

Thank you very much! First of all, I’m convinced that keeping non-experts in the loop is the only way to meaningful climate policy, because the general population is essential to keeping politicians and industry accountable. When no-one cares but the experts, we become too easy to ignore. One way to get non-experts interested is through media that’s easy to understand and engage with, such as a piece of art with a short description. The art is the draw, and then the choice to read the brief or a more in-depth explanation of the topic is the viewer’s own choice. Finally, it’s a great way to get young people of all ages involved. Cheesy, but true, in my opinion: the kids are the future. We need them to care and understand.

Alongside researching glacial change you’ve also contributed to the Cryospheric Sciences (CR) Division’s outreach efforts through, for example, writing blog posts. How did you get involved with the Division?

I wrote my first blog post for the CR division after a cryolist call for authors. Then, at the virtual 2020 EGU, I attended a few CR virtual meet-ups and joined the team officially, as an editor and blog author. It’s such a motivated, brilliant and fun team, who genuinely care about science communication. I encourage anyone who feels like they have something cryo-related to write about, to contact us. Whatever your confidence and writing level is: there’s someone there to help you make a beautiful, interesting post.

Finally, what’s the future looking like for yourself?

I hope to finish my PhD in 2022 or early 2023, and will be looking for a postdoc position. As that’s not easy, who knows where I’ll end up! Besides that, I would like to focus on the mix of art and science a little more, and hope to one day set up an interactive science & art exhibit around climate change.