Ravaged by armed conflicts, a deep struggle with poverty, poor governance and horizontal inequality, some parts of Africa and other Global South regions are arguably the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Largely reliant on natural resources for sustenance, current and future changes in temperatures, precipitation and the intensity of some natural hazards threaten the food security, public health and agricultural output of low-income nations.

Climate change increases heat waves across Africa

Among other impacts, climate change boosts the likelihood of periods of prolonged and/or abnormally hot weather (heat waves). A new study, by researchers in Italy, reveals that in the future all African capital cities are expected to face more exceptionally hot days than the rest of the world.

The new research, published in the EGU open access journal Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, has found that extreme heat waves affected only about 37% of the African continent between 1981 to 2005 while in the last decade, the land area affected grew to about 60%. The frequency of heat waves also increased, from an average of 12.3 per year from 1981 to 2005 to 24.5 per year from 2006 to 2015.

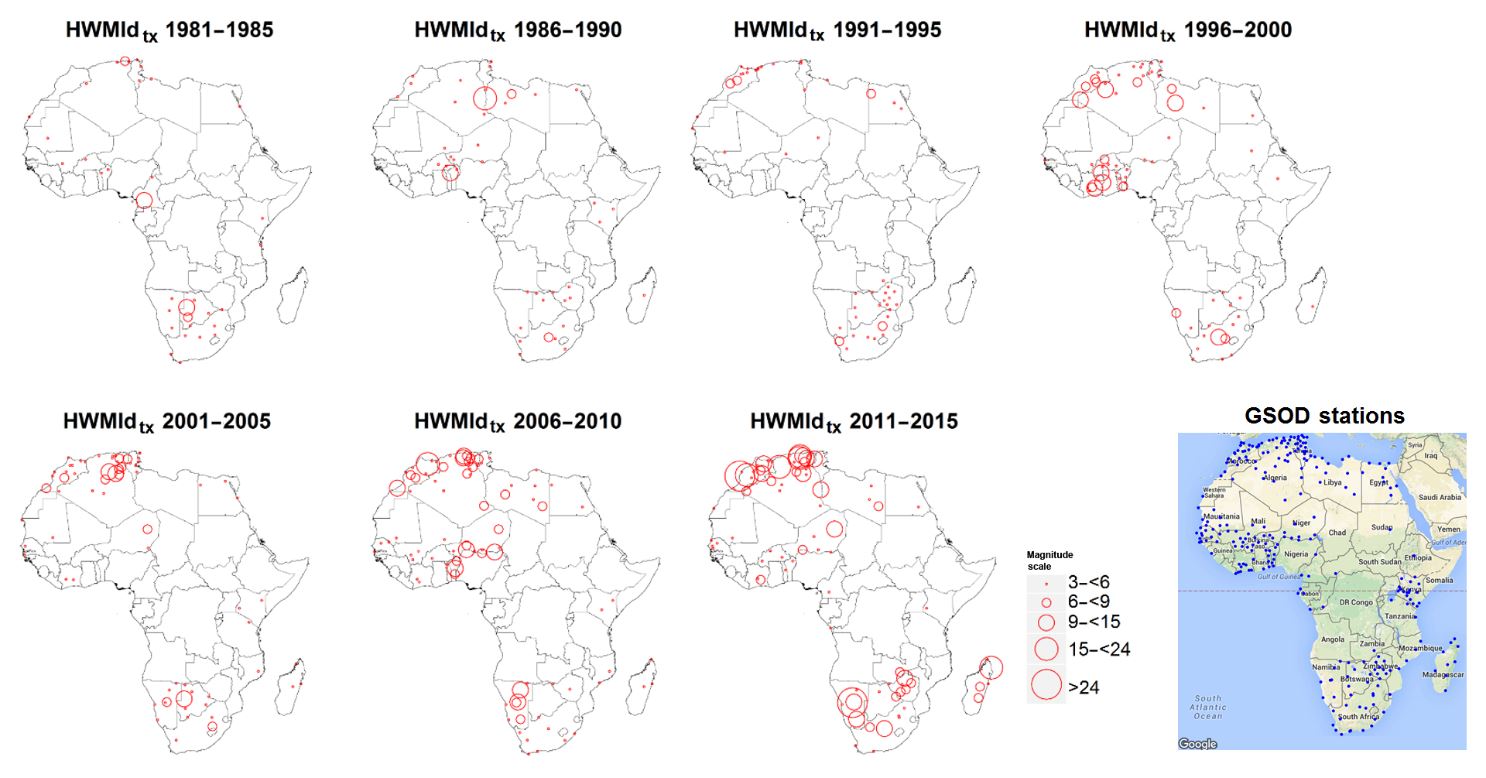

By merging information about the duration and the intensity of the recorded heat waves, the authors of the study were able to quantify the heat waves using a single numerical index which they called the Heat Wave Magnitude daily (HWMId). The new measure allowed the team to compare heatwaves from different locations and times.

Geographically plotting the HWMId values for daily maximum temperatures over five-year periods from 1981 to 2015, clearly showed there has been an increase, not only in the number of heat waves and their distribution across the continent, but also an escalation in their intensity (see the figure below). The trend is particularly noticeable since 1996 and peaks between 2011 and 2015.

Heat Wave Magnitude Index daily of maximum temperature (HWMIdtx) for 5-year periods of Global Surface Summary of the Day (GSOD) gauge network records from 1981 to 2015. The bottom-right panes show the spatial distribution of the GSOD station employed in this study. From G. Ceccherini et al. 2016 (click to enlarge).

The figure also highlights that densely populated areas, particularly Northern and Southern Africa, as well as Madagascar, are most at risk.

The rise in occurrences of extreme temperature events will put pressure on already stretched local infrastructure. With the elderly and children most at risk from heat waves, the health care needs of the local population will increase, as will the demand for electricity for cooling. Therefore, further studies of this nature are required, to quantify the implications of African heat waves on health, crops and local economies and assist government officials in making informed decisions about climate change adaptation policies.

Lessons learned from climate adaptation strategies

In the face of weather extremes across Africa including heat waves, droughts and floods, it is just as important to carefully assess the suitability of climate change adaptation policies, argues another recently published study in the EGU open access journal Earth System Dynamics.

Take Malawi, for instance, a severely poor nation: over 74% of the population live on less than a dollar ($) a day and 90% depend on rain-fed subsistence farming to survive. According to Malawi government figures, one-third of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) comes from agriculture, forestry and fishing. As a result, the country – and its population – is vulnerable to weather extremes, such as variability in the rainy season, prolonged dry spells and rise in the number of abnormally hot days.

A 2006 Action Aid report states that “increased droughts and floods may be exacerbating poverty levels, leaving many rural farmers trapped in a cycle of poverty and vulnerability. The situation in Malawi illustrates the drastic increases in hunger and food insecurity being caused by global warming worldwide.”

The Lake Chilwa Basin Climate Adaptation Programme (LCBCCAP) aims to enhance the resilience of rural communities surrounding Lake Chilwa to the impacts of droughts, floods and temperature extremes. The lake is a closed drainage lake (meaning it relies on rainfall to be replenished) in the south eastern corner of Malawi.

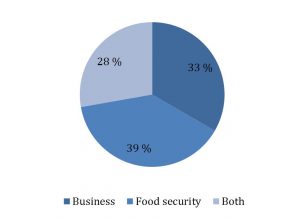

Perceptions of how climate change affects residents of the Lake Chilwa Basin. From H. Jørstad and C. Webersik, 2016 (click to enlarge).

The authors of the Earth System Dynamics study interviewed a group of 18 women (part of the LCBCCAP programme), back in early 2012, to understand how they perceived they were affected by climate change and whether the adaptation tools provided by the programme would meet their long-term needs.

The women agreed unanimously: climate in the Lake Chilwa Basin was changing. They reported that rainy seasons had become shorter and more unreliable, leading to droughts and dry spells. One of the women mentioned raising temperatures and fewer trees, due to overexploitation.

All those interviewed were part of the women fish-processing group, an initiative which sought to provide an alternative income for the women as traditional agricultural activities became unreliable due to erratic rainfall and prolonged dry seasons.

While the women’s new occupation did provide economic relief, the study authors highlight that the group’s new source of income was just as dependant on natural resources as agriculture.

Throughout the interviews, the women of the fish-processing group expressed concerns that the they thought Lake Chilwa might dry up completely by 2013.

“Yes, the lake will dry up and I will not have a business,” says Tadala, one of the women interviewed in the study. While another local woman said “Yes, lower water levels in the lake is threatening my business.”

Lake Chilwa has a long history of drying up: in the last century it has dried up nine times. If the lake dried up completely, the women of the fish-processing group would be out of business for 2 to 4 years. Even small drops in the water level affect the abundance of fish stocks.

Lake Chilwa has a history of drying up. These Landsat images show the net reduction of lake area between October 1990 and November 2013. show changes to the extensive wetlands (bright green) that surround Lake Chilwa. These wetlands are internationally recognized as an important seasonal hosting location for migratory birds from the Northern Hemisphere. Credit: USGS

The interviews were carried out in early 2012. The previous two years had seen very limited rainfall. Not enough to sustain the lake, but the situation, at the time of the interviews wasn’t critical. However, throughout the summer of 2012 the lake water levels started falling rapidly prompting the relocation of large groups of lakeshore residents. Those dependant on fishing to support their families were most affected.

The women fish-processing group is a good demonstration of how local communities can adopt low-cost measures to adjust to climate change. At the same time, it highlights the need to assess climate adaptation strategies to take into consideration whether they too are dependent on climate-sensitive natural resources. The new research argues that diversifying people’s livelihoods might provide better long-term coping mechanisms.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer

References and resources

Ceccherini, G., Russo, S., Ameztoy, I., Marchese, A. F., and Carmona-Moreno, C.: Heat waves in Africa 1981–2015, observations and reanalysis, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 115-125, doi:10.5194/nhess-17-115-2017, 2017

Jørstad, H. and Webersik, C.: Vulnerability to climate change and adaptation strategies of local communities in Malawi: experiences of women fish-processing groups in the Lake Chilwa Basin, Earth Syst. Dynam., 7, 977-989, doi:10.5194/esd-7-977-2016, 2016.

ActionAid: Climate change and smallholder farmers in Malawi: Understanding poor people’s experience in climate change adaptation, ActionAid International, 2006.

NASA: The consequences of climate change

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Understanding the Link Between Climate Change and Extreme Weather

National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA): Heat wave, a major summer killer

belgian beers

African continent one of the most vulnerable to climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported in early February that scientists are now 90% certain that human activities are causing climate change.