In the Southern Ocean and North Pacific lives a peculiar type of elephant seal. This group acts like any other marine mammal; they dive deep into the ocean, chow down on fish, and sunbathe on the beach. However, they do all this with scientific instruments attached to their heads. While the seals carry out their usual activities, the devices collect important oceanographic data that help scientists better understand our marine environment.

The practice of tagging elephant seals to obtain data started in 2004, and today equipped seals are the largest contributors of temperature and salinity profiles below of the 60th parallel south. You can find all sorts of data that has been collected by instrumented sea creatures through the Marine Mammals Exploring the Oceans Pole to Pole database online.

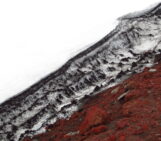

The female elephant seal, pictured here at Point Suzanne on the eastern end of the Kerguelen Islands in the Southern Ocean, is a member of this unusual headgear-wearing cohort. This particular seal had been roaming the sea for several months with the device (also known as a miniature Conductivity-Temperature-Depth sensor) on her head. As the seal dove hundreds of metres below the sea surface, the instrument captured the vertical profile of the area, recording the ocean’s temperature and salinity, as well as chlorophyll a fluorescence and concentrations. When the seal resurfaced, the sensor sent the data it had accrued to scientists by satellite.

Etienne Pauthenet, a PhD student at Stockholm University who was involved in a seal tagging campaign, had a chance to snap this photo before tranquilising the seal and retrieving the tag.

Using elephant seals and other marine mammals to collect data gives scientists the opportunity to analyse remote regions of the ocean that aren’t very accessible by vehicles. Studying these parts of the world are important for gaining insight on how oceans and their inhabitants are responding to climate change, for example. With the help of data-gathering elephant seals, researchers are able to amass in situ measurements from regions that previously had been hard to reach, apply this data to oceanographic models, and make predictions on ocean climate processes.

While gathering data via elephant seals are crucial to oceanographic research, Pauthenet explains that the practice is sometimes quite difficult. “It can be complicated to find back the seal, because of the Argo satellite signal precision. The quality of the signal depends on the position of the seal, if she is lying on her back for example, or if she is still in the water.”

While on the research campaign, Pauthenet and his colleagues were stationed at a small cabin on the shore of Point Suzanne and they walked the shore every day in search of the seal, relying on location points transmitted from a VHF radio. After seven days they finally located her and removed her valuable crown. The seal was then free to go about her business, having given her contribution to the hundreds of thousands of vertical profiles collected by marine mammal citizen scientists.