Throughout October and November, the world of (Earth science) Twitter was taken by storm: Day after day, Eddie Dempsey (a lecturer at the University of Hull, and @Tectonictweets for those of you more familair with his Twitter handle) pitted minerals against each other, in a knock out style popular contest. The aim? To see which mineral would eventually be crowned the best of 2017.

Who knew fiery (but good natured) rows could explode among colleagues who felt, strongly, that magnetite is far superior to quartz or plagioclase? The Mineral Cup hashtag (#MinCup) was trending, it was in everyone’s mouth. Who would you vote for today?

What started as a little fun, became a true example of great science communication and how to bring a community of researchers, scattered across the globe, together.

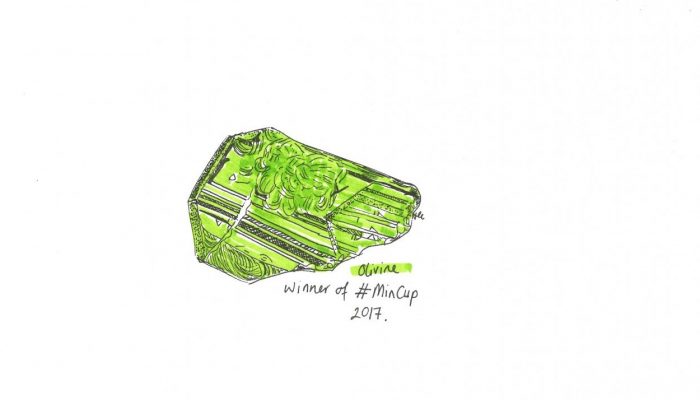

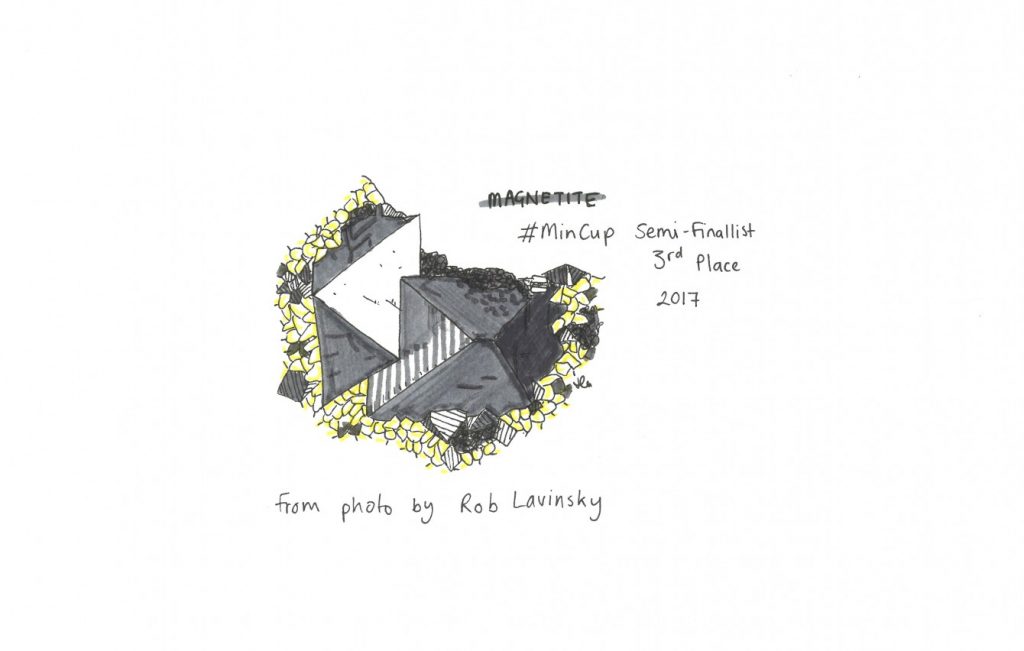

And then Hazel Gibson (former EGU Press Assistant, @iamhazelgibson) came along. She was an active participant in the competition, but also contributed beautiful sketches of every mineral featured, and shared them for all to see by tagging them with the #MinCup hashtag. We all know that a picture is worth more than a thousand words, so when Hazel’s hand drawn sketches where paired with an already rocking contest, it’s impact and reach was truly cemented.

Between them, Eddie and Hazel had managed to elevate the humble mineral to new heights.

Why do minerals matter?

Minerals are hugely underrated. They are often upstaged by the heavy-weights of the geosciences: volcanoes, earthquakes, hurricanes, fossils and melting glaciers (to name but a few).

But they shouldn’t be.

Minerals are the building blocks of all rocks, which in turn, are the foundation of all geology.

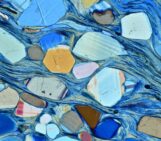

Whether you study the processes which govern how rivers form, or ancient magnetic fields, or fossils, chances are your work will, at some stage, involve looking at, studying, or at the very least understanding (some) minerals. Mineralogy 101 (or whatever it’s precise name was at your university) is a rite of passage for any aspiring Earth scientist. I still remember hours spent painstakingly looking down a microscope, drawing and annotating sketches trying to decipher the secrets of the Earth’s ancient past, locked in minerals.

And that’s just the beginning.

Minerals are of huge economic and, therefore societal importance, too. Many minerals are vital ingredients in house-hold products and contribute to the manufacturing processes of many others. Yet, they fail to make headlines and their true significance, often, goes unnoticed.

So, in hopes to further highlight the relevance and importance of minerals, I’ve picked a few of the #MinCup minerals and explained why they (should) matter (to you).

Gypsum

Gypsum will form in lagoons, where ocean waters are high in calcium and sulfate content, and where the water evaporates slowly overtime. In rocks, it is associated with sedimentary beds which can be mined to extract the mineral, but it can also be produced by evaporating water with the right chemical composition.

Gypsum has been used in construction and decoration (in the form of alabaster) since 9000 B.C. Today, it has a wide variety of common uses. Did you know that many fruit juice companies use gypsum to aid the extraction of the liquid? It is also used in bread and dough mixes as a raising agent. And it’s uses aren’t limited to just the food and drink industry. It is also commonly used as a modelling material for tooth restorations and helps keeps us safe when added to plastic products where it acts as a fire retardant.

Magnetite

Geologically speaking, magnetite holds the clues to understand the Earth’s ancient magnetic field. Credit: Hazel Gibson

Typically, greyish black or black, magnetite is an important iron ore mineral. It occurs in many igneous and volcanic rocks and is the most magnetic of all minerals. For it to form, magma has to cool, slowly, so that the minerals can form and settle out of the magma.

Due to its magnetic nature, it has fascinated human-kind for centuries: it paved the way for the invention of the modern compass. The iron content in magnetite is higher than its more common cousin haematite, making it very sought after. Iron ore is the source of steel, which is used universally throughout modern infrastructure.

Geologically speaking, magnetite holds the clues to understand the Earth’s ancient magnetic field. As magnetite-bearing rocks form, the magnetite within them aligns with the Earth’s magnetic field. Since this rock magnetism does not change after the rock forms, it provides a record of what the Earth’s magnetic field was like at the time the rock formed.

Diamond

Arguably, one of the most well-known of the minerals, diamond is unique, not only for its beauty and the high prices it reaches, but also for its properties. Not only is it the hardest known mineral, it is also a great conductor of heat and has the highest refractive index of any mineral.

Though mostly sought after by the jewellery industry, only 20% of all diamonds are suitable for use as a gem. Due to it’s hardness, diamond is mined for use in industrial processes, to be used as an abrasive and in diamond tipped saws and drills. Its optical properties mean it is used in electronics and optics; while it’s conductive properties mean it is often used as an insulator too.

Olivine

Last, but absolutely not least, let’s talk about Olivine – the winner of #MinCup 2017.

Olivine is a pretty, commonly green mineral. Because it forms at very high temperatures, it is one of the first minerals to take shape as magma cools, and given enough time, can form specimens which are easily seen with the naked eye. Changes in the behaviour of seismic waves as they traverse the Earth indicate that Olivine is an important component of the Earth’s inner layer – the Mantle.

It’s a relatively hard mineral, but overall hasn’t got highly sought-after properties and, as result, has been used rather sparingly in industrial processes. In the past it has been used in blast furnaces to remove impurities from steel and to form a slag, as well as a refractory material, but both those uses are in decline as cheaper materials come to the market.

Perhaps better known is its gemstone counterpart: peridot, a magnesium rich form of Olivine. It has been coveted for centuries, with some arguing that Cleopatra’s famous ‘emeralds’, where in fact peridote. Until the mid-90s the US was the major exporter of the gem stones, but deposits in Pakistan and China now challenge the claim.

So, do you think Olivine was the rightful winner of #MinCup 2017? With a new edition of the popular contest set to return in 2018, perhaps it’s time to shout about the properties and uses of your favourite mineral from the roof tops? Not only might it ensure it is crowned winner next year, but you’ll also be contributing to making the value of minerals known to the wider public. Heck! If you’d like to tell us all about the mineral you think should be the next champion, why not submit a guest post to GeoLog?

In the meantime, if you haven’t already got your hands on one, Hazel tells me there are a few of her charity #MinCup 2017 calendars up for grabs, so make sure to secure your copy – and contribute to a good cause at the same time.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer