Though now submerged under 53 m of ocean waters, there once was a land bridge which connected North America with Asia, allowing the passage of species, including early humans, between the two continents. A new study, published in the EGU’s open access journal Climate of the Past, explores when the land bridge was last inundated, cutting off the link between the two landmasses.

The Bering Strait, a narrow passage of water, connects the Arctic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. Located slightly south of the Arctic Circle, the shallow, navigable, 85 km wide waterway is all that separates the U.S.A and Russia. There is strong evidence to suggest that, not so long ago, it was possible to walk between the two*.

The Paleolithic people of the Americas. Evidence suggests big-animal hunters crossed the Bering Strait from Eurasia into North America over a land and ice bridge (Beringia). Image: The American Indian by Clark Wissler (1917). Distributed via Wikipedia.

In fact, though the subject of a heated, ongoing debate, this route is thought to be one of the ones taken by some of the very first human colonisers of the Americas, some 16, 500 years ago.

Finding out exactly when the Bering Strait last flooded is important, not only because it ends the last period when animals and humans could cross between North America and northeast Asia, but because an open strait affects the two oceans it connects. It plays a role in how waters move around in the Arctic Ocean, as well as how masses of water with different properties (oxygen and/or salt concentrations and temperatures, for example) arrange themselves. The implications are significant: currently, the heat transported to Arctic waters (from the Pacific) via the Bering Strait determines the extend of Arctic sea ice.

As a result, a closed strait has global climatic implications, which adds to the importance of knowing when the strait last flooded.

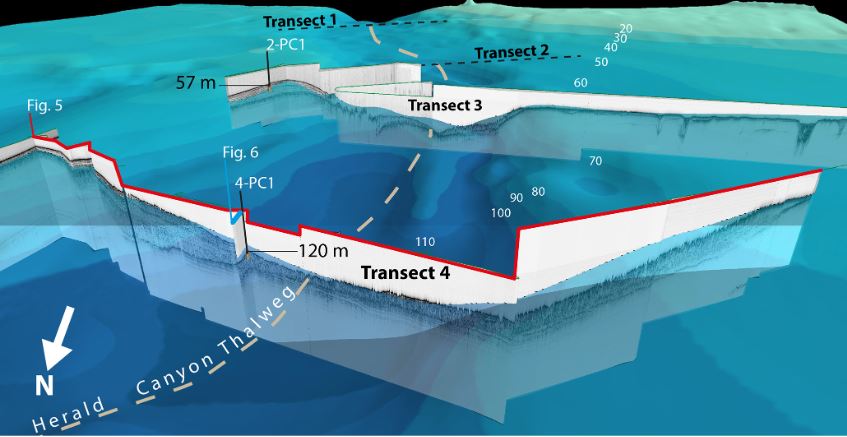

The new study uses geophysical data which allowed the team of authors to create a 3D image of the Herald Canyon (within the Bering Strait). They combined this map with data acquired from cylindrical sections of sediment drilled from the ocean floor to build a picture of how the environments in the region of the Bering Strait changed towards the end of the last glaciation (at the start of a time known as the Holocene, approximately 11,700 years ago, when the last ‘ice age’ ended).

At depths between 412 and 400 cm in the cores, the sediment experiences changes in physical and chemical properties which, the researchers argue, represent the time when Pacific water began to enter the Arctic Ocean via the Bearing strait. Radiocarbon dating puts the age of this transition at approximately 11, 000 years ago.

Above this transition in the core, the scientist identified high concentrations of biogenic silica (which comes from the skeletons of marine creatures such as diatoms – a type of algae – and sponges); a characteristic signature of Pacific waters. Elevated concentrations of a carbon isotope called delta carbon thirteen (δ 13Corg), are further evidence that marine waters were present at that time, as they indicate larger contributions from phytoplankton.

The sediments below the transition consist of sandy clayey silts, which the team interpret as deposited near to the shore with the input of terrestrial materials. Above the transition, the sediments become olive-grey in colour and are exclusively made up of silt. Combined with the evidence from the chemical data, the team argue, these sediments were deposited in an exclusively marine environment, likely influenced by Pacific waters.

Combining geophysical data with information gathered from sediment cores allowed the researchers to establish when the Bering Strait closed. This image is a 3-D view of the bathymetry of Herald Canyon and the chirp sonar profiles acquired along crossing transects. Locations of the coring sites are shown by black bars. Figure taken from M. Jakobsson et al. 2017.

The timing of the sudden flooding of the Bering Strait and the submergence of the land bridge which connected North America with northeast Asia, coincides with a period of time characterised by Meltwater pulse 1B, when sea levels were rising rapidly as a result of meltwater input to the oceans from the collapse of continental ice sheets at the end of the last glaciation.

The reestablishment of the Pacific-Arctic water connection, say the researchers, would have had a big impact on the circulation of water in the Arctic Ocean, sea ice, ecology and potentially the Earth’s climate during the early Holocene. Know that we are more certain about when the Bering Strait reflooded, scientist can work towards quantifying these impacts in more detail.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer

*Authors’s note: In fact, during the winter months, when sea ice covers the strait, it is still possible to cross from Russia to the U.S.A (and vice versa) on foot. Eight people have accomplished the feat throughout the 20th Century. Links to some recent attempts can be found at the end of this post.

References and resources:

Jakobsson, M., Pearce, C., Cronin, T. M., Backman, J., Anderson, L. G., Barrientos, N., Björk, G., Coxall, H., de Boer, A., Mayer, L. A., Mörth, C.-M., Nilsson, J., Rattray, J. E., Stranne, C., Semiletov, I., and O’Regan, M.: Post-glacial flooding of the Bering Land Bridge dated to 11 cal ka BP based on new geophysical and sediment records, Clim. Past, 13, 991-1005, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-13-991-2017, 2017.

Barton, C. M., Clark, G. A., Yesner, D. R., and Pearson, G. A.: The Settlement of the American Continents: A Multidisciplinay Approach to Human Biogeography, The University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, 2004.

Goebel, T., Waters, M. R., and Rourke, D. H.: The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas, Science, 319,1497–1502, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153569, 2008

Epic explorer crossed frozen sea (BBC): http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/humber/4872348.stm

Korean team crossed Bering Strait (The Korean Herald): http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20120301000341