Bangor, once a tropical paradise on the coast of Gondwana, then a volcanic wasteland at the foothills of an immense mountain chain. The region would then be buried under glaciers for thousands of years before finally developing into an unassuming Welsh University town.

Wales’ place in modern geology

Perhaps you have looked at the chronostratigraphic chart of Earth history and wondered what the story is behind the names for each geological period. Some are intuitively named, like the Archean, which is Greek for beginning, or Carboniferous which is named because of the vast coal deposits laid down during the period. However, what is the etymology of the other periods?

The Cambrian period gets its name from Cambria which is the Latinised name for Wales (Cymru), and the Ordovician and Silurian periods are both named after Welsh tribes who lived in Wales when the Romans arrived in Britain. These periods are named as such because Wales has a diverse geology which acted as a natural laboratory for geologists such as Roderick Murchison, Adam Sedgwick (Charles Darwin’s geology tutor), and Charles Lapworth who each used the rocks of Wales to describe evidence for each period.

The city of Bangor

Bangor is one of the smallest cities this series has covered. In the 2011 census, the non-student population was around 19,000 people, with around 10,000 students sharing the city during semester time. Furthermore, it is not as old as some of the other cities covered in this series either, however it is one of the oldest cities in Wales, founded as a bishopric around the 6th century C.E.

The majority of the city sits in a large valley with the town center at the base, and the university on the top of the Northern edge. The city is surrounded to the South by mountains. During some parts of the year the shadow of Bangor mountain covers the town center, and from many places on the northern edge of the valley you can see the Snowdonia mountain range, with one of the highest peaks in England and Wales. Further to the North is the Island of Anglesey. This island is a large and relatively flat landmass separated from the mainland by a narrow strait.

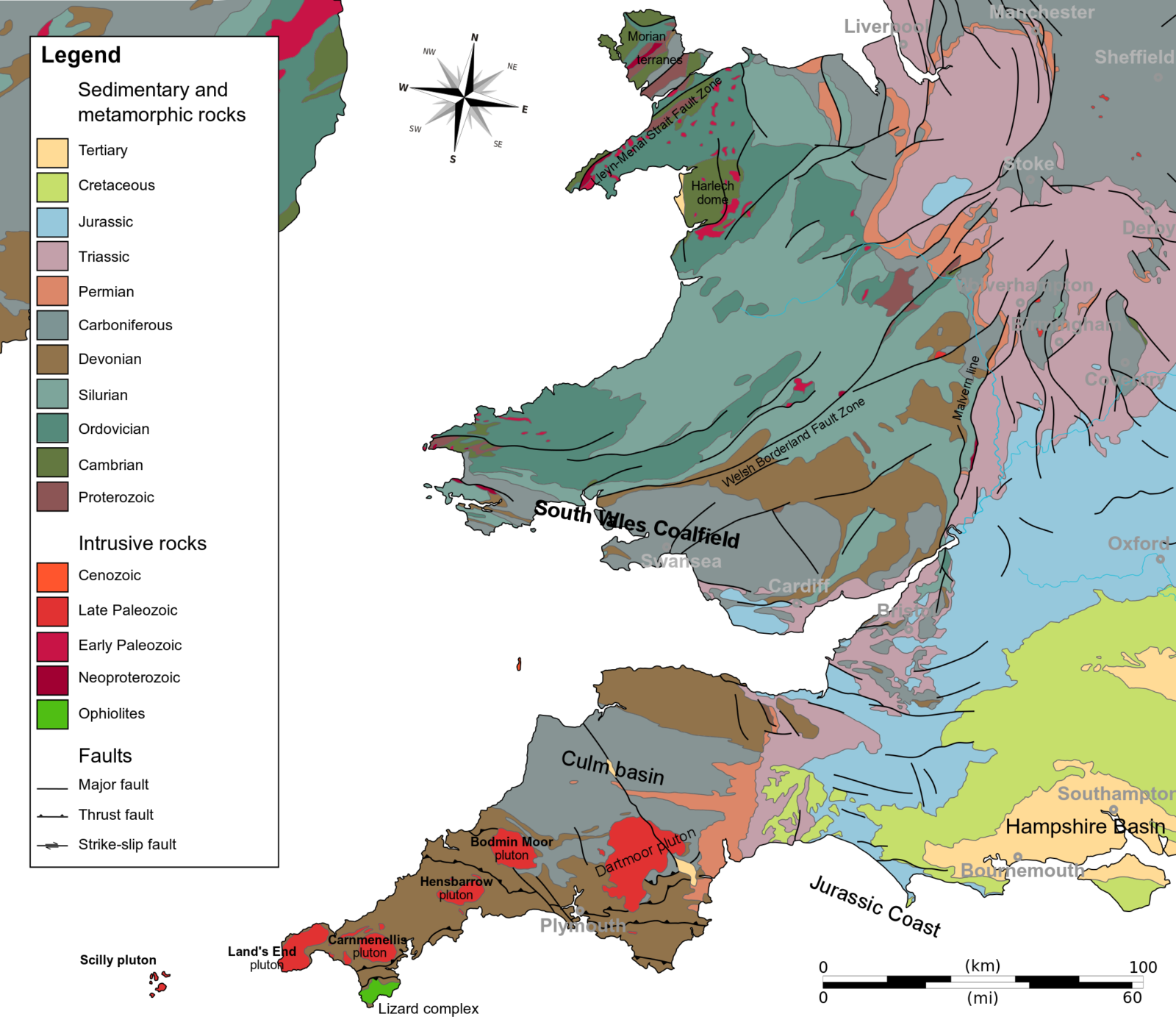

Looking initially at the greater region – Snowdonia and Anglesey – the area is primarily made of rocks dating from the Pre-Cambrian to the Silurian, although Anglesey is striped by older rock assemblages as well as the aforementioned periods.

Sedimentary and metamorphic rocks of Wales. Credit: Woudloper, Wikipedia

The Cambrian period

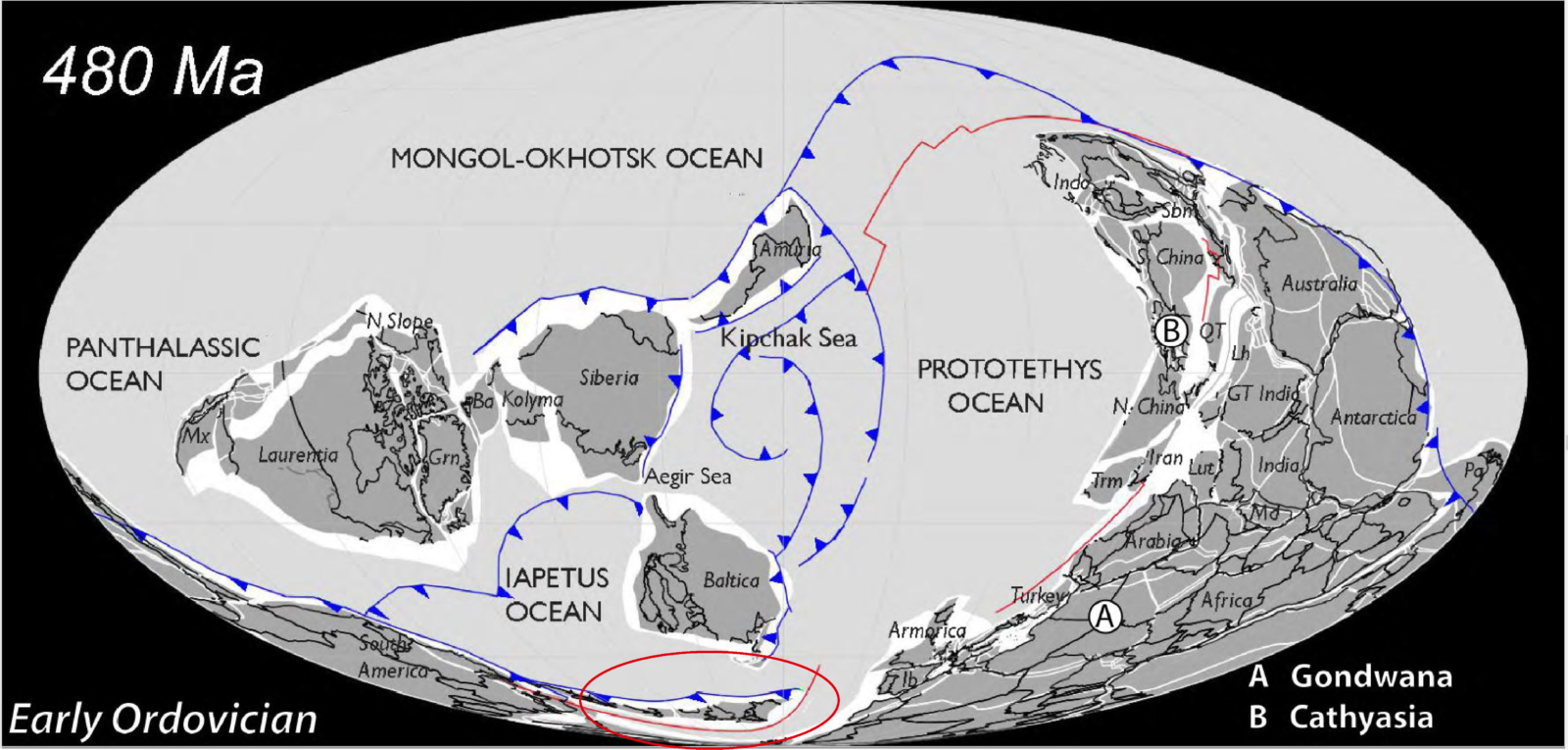

During the Cambrian period, Bangor sat on the tropical coast of Gondwana (Scotese & Mckerrow 1990), sandstones of this period show that the ocean probably regularly inundated the low-lying area. Furthermore, volcanic ash and tufts found in the area today show that regular volcanic eruptions affected the region. The area probably resembled Sumatra or Peru in geography, a coastal, sandy environment with active volcanism in the backdrop.

A world map reconstruction of the very early Ordovician period with the craton England and Wales is situated on circled in red. This map is used in lieu of the late Cambrian map present in the Atlas because the Mollweide map projection makes it difficult to see the craton at 500 Ma. credit: Scotese Atlas of Ancient Oceans and Continents.

The Ordovician period

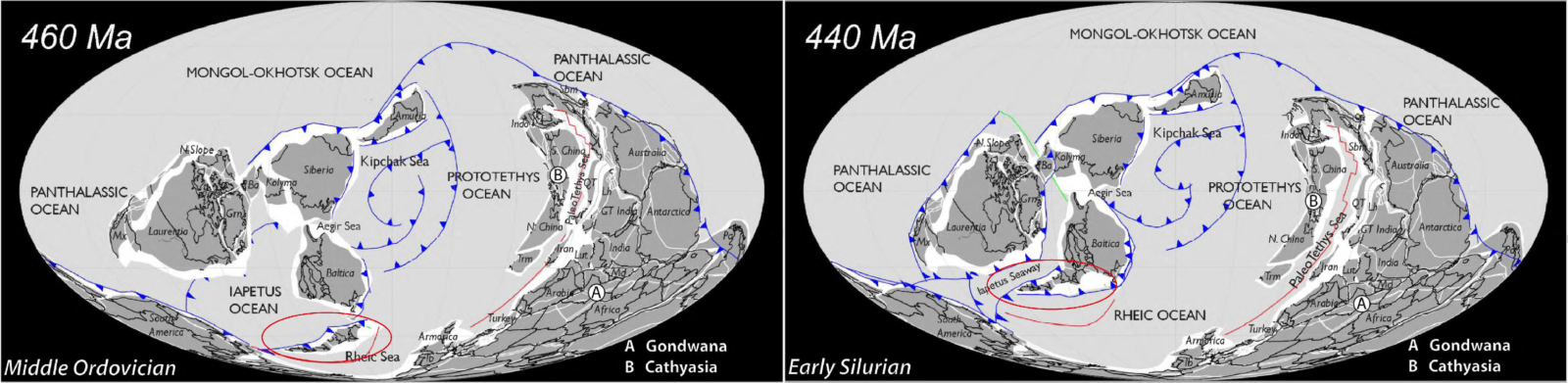

During the Ordovician period, Bangor made up part of a small continent called Avalonia which had rifted away from mainland Gondwana. This continent was drifting North as the Iapetus ocean was closing. The active subduction around the continent caused regular and large-scale, explosive volcanic eruptions. Remnants of these volcanoes and eruptions can be found in Snowdonia today as rhyolite rich lava deposits.

460 – 420 million years ago, with Avalonia circled in red. Credit: Scotese Atlas of Ancient Continents and Oceans

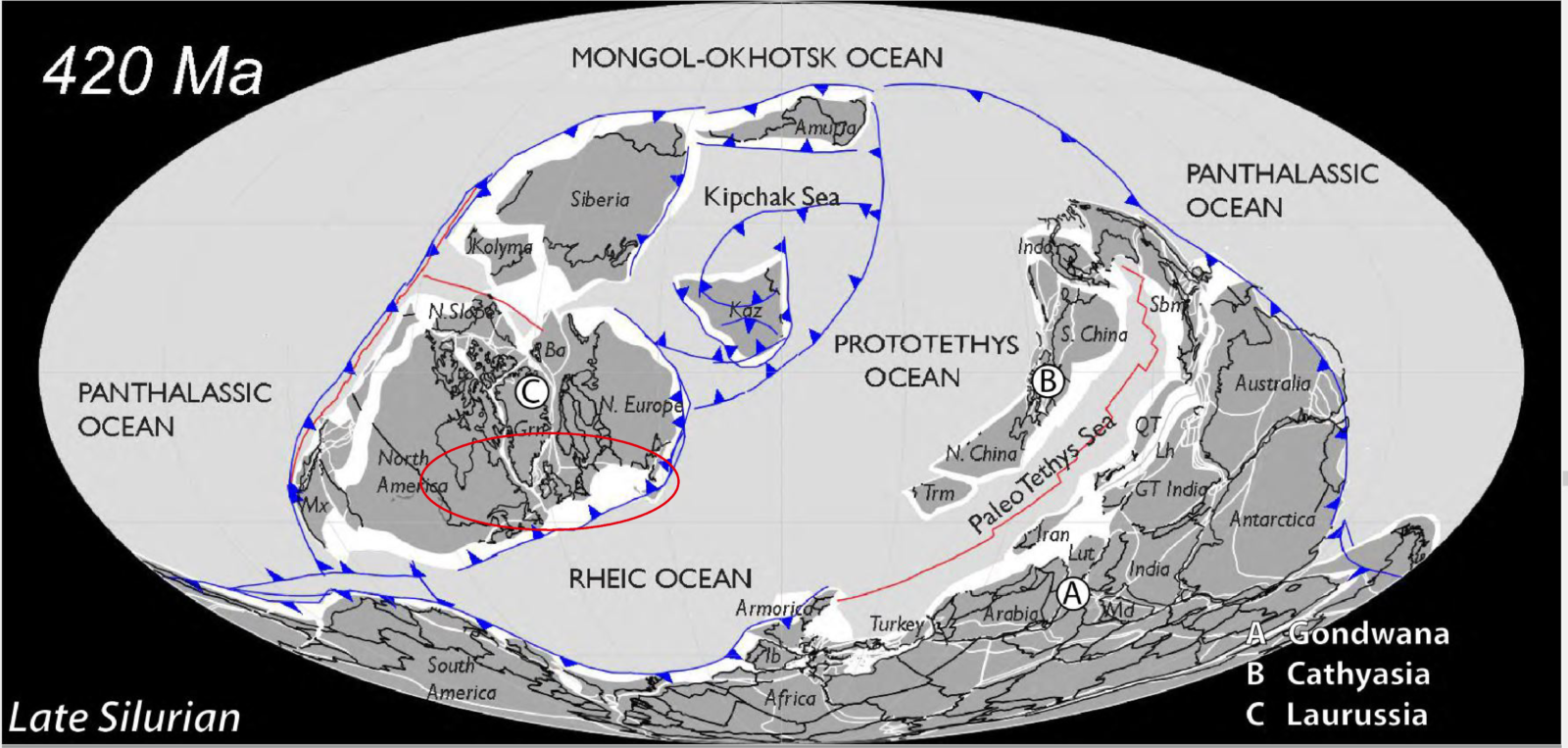

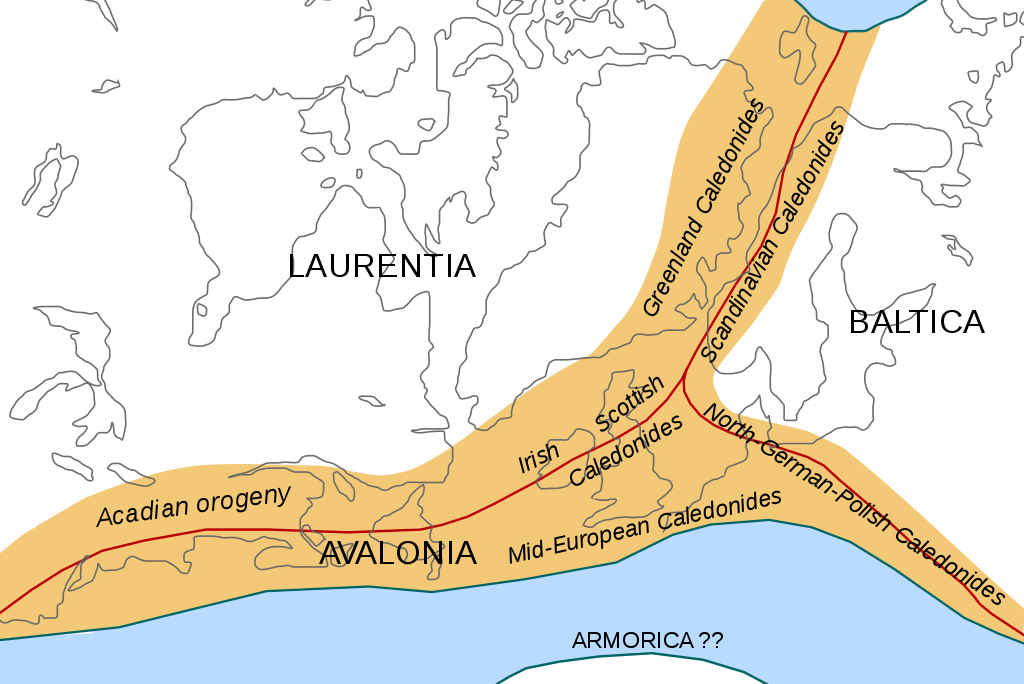

Bangor and the rest of Avalonia were involved in the Caledonian orogeny which marked the final closure of the Iapetus ocean (Mckerrow et al., 2000). The orogeny is named after the Latinised name for Scotland (Caledonia). This orogenic event created many of the mountains seen in Wales and Scotland today. The compressive force of the collision of Avalonia, Baltica, and Laurentia metamorphosed the sand and ash which had been laid down around Bangor and Snowdonia which created a type of rock called slate. The faults and folds left by the mountain-building are still visible in some of the foothills of Snowdonia with the most famous being in Cwm Idwal.

An illustration of the Caledonian orogeny. Credit Woudloper, Wikipedia

Post Caledonian Orogeny

Between the period of the Caledonian orogeny and today, Pangea formed and broke up, however much of the geological material laid down in this period is either rare, or completely missing from North Wales. This is because Snowdonia and North Wales has been covered by regular glaciations during the quaternary which has eroded and muddled much of the material in the upper sequences of the geological record of the area.

The most understood glaciation was the most recent Devensian glaciation, which occurred 115,000 – 11,500 Ka (including the Younger Dryas period). It was likely that during this entire period, Bangor and Snowdonia were covered by large ice sheets. These ice sheets left Wales with the morphology it has today, craggy mountains, rolling hills and deep glacial valleys. North Wales initially confused many Geologists of the 17th and 18th century because it had features which looked similar to those seen in the Alps. The mountains of the area had evidence of glaciers, but it was not cold enough to support perennial snow and ice. Therefore in the past it must have been colder and glaciers used to cover the area but they since retreated. Cwm Idwal is a good example of this relict glacial geology, Cwm is the Welsh name for a Cirque, which is the more commonly used term for a depression in the land formed by glacial erosion. Many of the rocks around Snowdonia are also covered with striations indicative of glacial scraping by rocks carried along by the glacial ice.

Cwm Idwal during the winter. Credit: Crown copyright (2014) Visit Wales

Bangor, Anglesey, and Snowdonia’s mineral wealth

The sand and mudstones of North Wales were metamorphosed during the Caledonian orogeny. The sand and mudstones were turned into slate which can be easily split along the grain, while retaining its strength across the grain, this means it can be made into thin plates. The slate is resistant to water and frost intrusion, and is very durable making it an excellent material for roofing. During the 19th century, Snowdonia slate was widely used for this purpose. The use of Snowdonia slate is recorded as far back the Roman occupation of Britain with a Roman fort in the area allegedly using the material in its construction.

The Ordovician and Silurian volcanic eruptions in the area laid down metal deposits which can be found in Anglesey today. Parys Mountain on Anglesey has a copper source which was exploited during the Bronze age, Roman occupation, and during the industrial revolution.

Wales as a natural laboratory

While North Wales boasts a useful mineral wealth, the area is arguably more important as a natural laboratory. The erosion of much of the Mesozoic and Permian material from North Wales, due to both glacial and fluvial processes has exposed the older rock beneath. This rock is further exposed by uplift and folding caused by the Caledonian orogeny. Because of this Snowdonia is an excellent natural laboratory for studying these rocks, and because of recent glaciations, the mountain can also be used to study the effects of the last ice age on the geography of the area. It is not just the mountains of the area that are useful, to the North, on Anglesey, there are large assemblages that make up part of the Monian terranes, however they are only partly exposed and are muddled and covered by younger rocks. Anglesey has such a complex geology that it is still debated to this day.

“Imagine a jigsaw puzzle, almost complete around the edges (the coast), but with big holes in the middle (inland) – and those few completed bits in the middle all radically different from one another. That’s Anglesey’s geology in a nutshell” – Geomon.co.uk

Together Anglesey and Snowdonia were the natural laboratories which gave evidence for the argument of the geological periods of the Cambrian, Ordovician and Silurian. These laboratories are still used to educate geologists who study in Wales, Snowdonia and Anglesey where I learned much of the Geology I know today.

References

McKerrow, W.S., MacNiocaill, C., and Dewey, J.F., (2000). The Caledonian Orogeny redefined. Journal of the Geological Society, 157, 1149-1154, https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs.157.6.1149

Scotese, C.R., and McKerrow, W.S., (1990). Revised world maps and introduction. Palaeozoic Palaeogeography and Biogeography, Geological Society memoir, 12, 1-21.