The beautiful island of Taiwan (as given by its colonial name, Ilha Formosa) is primarily known for its lush tropical forests, delicious culinary cuisine, bubbling hot springs, and a bustling cityscape. But, what does Taiwan have to do with the cryosphere? Before you resist the urge to leave and get a bubble tea, read on to find out about Taiwan’s cryospheric past!

From cities to mountains

Taiwan is one of the most densely populated areas in the world, with a population density reaching nearly 30,000 people per square kilometre in the island’s largest city of Taipei. However, Taiwan is also a paradise for geoscientists due to its high orogenic activity, being situated directly on the infamous “Ring of Fire”. As a result, the majority of Taiwan is covered by an impressive series of mountain ranges that reach nearly 4,000 metres at its highest point. Large amounts of snow are deposited in these regions during the winter season, with snow depths regularly reaching up to 2 metres in specific regions. In fact, the second highest peak at 3,886 m, Snow Mountain (雪山) is named from this phenomenon. Temperatures at these altitudes regularly drop to -10°C, but strong radiation from the equatorial sun causes the snowpack to melt and transform into ice that then blankets large sections of mountaineering trails. During the winter season, it is actually a requirement to bring crampons and ice axes on these routes.

Even areas at lower elevations may experience occasional snowfall. In 2016, the mountains surrounding Taipei City were dusted with a layer of snow during a cold snap!

The main island of Taiwan is located east of China, and is situated between Japan and the Philippines. [Credit: Wikipedia]

Taiwan and the Last Glacial Maximum

One of the many glacial cirques surrounding Snow Mountain and the Sheipa National Park (雪霸國家公園). [Credit: TJ Young]

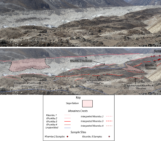

Unfortunately, the majority of rock types found in these high mountains are not suitable for accurate exposure dating techniques: a well-established method to gather time-related information about the exposure of a rock to the atmosphere. Because of its high tectonic activity, the implementation of exposure dating in Taiwan is difficult, making it challenging to obtain precise dates to reconstruct the evolution of its landscape. However, it is still possible to reconstruct its geological and cryospheric history in combination with geomorphological landforms that represent past glaciation. Many of these landforms are still clearly visible today, and lie along popular mountaineering routes, particularly cirques, which are impressive bowl-shaped valleys formed through glacial erosion. You can see a beautiful example below!

The Nanhu Cirque (南湖圈谷), with the Nanhu Cabin serving mountaineers that traverse this region. [Credit: TJ Young]

Snow and ice in the languages of Taiwan

Although the majority of Taiwan’s population today descend from Han Chinese settlers and speak various Chinese languages, around 2% of the current population belong to diverse indigenous groups that far predate the waves of Chinese migration, many of whom claim the mountainous regions of Taiwan as their traditional homelands. While their numbers may seem small, the indigenous peoples of Taiwan share a special connection and a common ancestry with peoples all across the Pacific Ocean as well as Madagascar, and collectively they are known as Austronesians. Although Austronesian languages show remarkable consistencies and similarities all across the family, one feature that sets the indigenous languages of Taiwan (known as Formosan languages) apart is the existence of native words for ‘snow’ and ‘ice’. These include sulja in Paiwan (one of the largest groups from the southern mountains) and ulhza in Thao (a smaller group from the central mountains), and the existence of these words and meanings clearly shows that the indigenous peoples of Taiwan regularly experienced (and still experience) such cryospheric phenomena.

Interestingly, this linguistic artefact also tells a story of the Austronesian migration out of Taiwan further into the Pacific, as related words are not found in the many languages of the Philippines, Indonesia, and beyond, where snow and ice are rarely encountered. It was not until many centuries later when they reached the mountainous islands of New Zealand and Hawai’i, however, that new terms for ‘snow’ and ‘ice’ were coined to describe the glaciated and snow-capped landscapes there, such as hukarere and hukapapa in Māori and hau in Hawai’ian.

Further reading

- Blust & Trussel (2013) The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress. Oceanic Linguistics 52:493-523.

- Cui et al. (2002) The Quaternary glaciation of Shesan Mountain in Taiwan and glacial class in monsoon areas. Quaternary International 97/98:147-153, DOI: 10.1016/S1040-6182(02)00060-5.

- Heibenstreit et al. (2006) Late Pleistocene and early Holocene glaciations in Taiwanese mountains. Quaternary International 147:76-88, DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2005.09.009.

- Porter (2000) Snowline depression in the tropics during the Last Glaciation. Quaternary Science Review 20:1067-1091, DOI: 10.1016/S0277-3791(00)00178-5.

Edited by Giovanni Baccolo

Twin brothers T.J. and C.J. Young were born in Taipei, Taiwan, and while they currently work and study in seemingly disparate fields and places, their paths occasionally converge from time to time. They tweet as @tjy511 and @seajayseajay respectively.

Twin brothers T.J. and C.J. Young were born in Taipei, Taiwan, and while they currently work and study in seemingly disparate fields and places, their paths occasionally converge from time to time. They tweet as @tjy511 and @seajayseajay respectively.

TJ (楊敦然) is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, where he uses field geophysics to investigate the role of shear margins on ice sheet dynamics as part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration. Prior to taking up his postdoc, T.J. completed mandatory national service in Taiwan as a park ranger in Taroko National Park (太魯閣國家公園), where he was involved in the management and conservation of some of Taiwan’s high mountain ranges. T.J. is currently the ECS representative of the EGU’s Cryosphere Division.

CJ (楊淳然) is currently a PhD student in the Department of Linguistics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he investigates various aspects of grammar, prosody, and their interactions in the indigenous Austronesian languages of Taiwan, with a special focus on the Tao/Yami language of Orchid Island. During his year of mandatory national service in Taiwan, CJ served as an elementary English teacher in Pingtung County (屏東縣), where he also participated in local revitalization efforts of Paiwan culture and language. CJ also holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in flute performance.