Welcome to Kongsfjorden in Svalbard. The front of the glaciers terminating into the sea is an ecological hotspot, home to many marine animals, like kittiwakes, who love to hunt here. They feed on small fish and shrimp, which at marine-terminating glacier fronts are brought to the surface by upwelling glacial meltwater.

Retreating glaciers lose their contact with the ocean

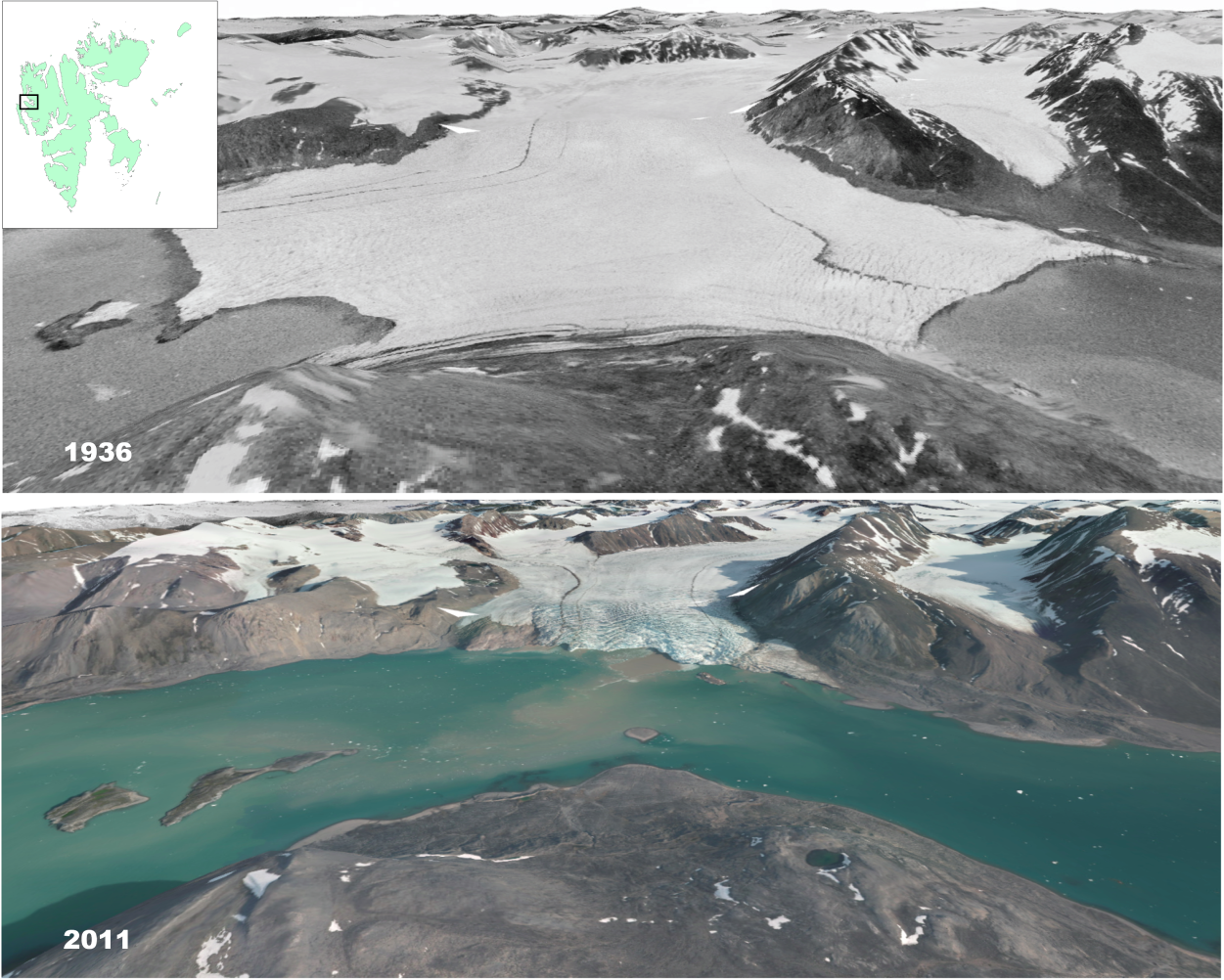

As the planet warms these marine-terminating glaciers are retreating inland and may lose their contact with the ocean. In addition to melting, more rain will fall over the glaciers instead of snow, as last week’s blog post mentioned. The Svalbard Islands are warming seven times faster than the global average. By comparing historical photos using structure-from-motion photogrammetry, a recent study in Nature suggests that Svalbard glaciers will double their mass loss by 2100.

Between 1936 and 2010 the ice thickness has been reduced by an average of 25 m, or 0.36 m per year. Since temperature and glacier height change are tightly linked, you can use this link to predict ice loss in future climate scenarios. By 2100 the ice loss is predicted to be 0.67 to 0.92 meter per year, depending on the emission scenario.

Aerial photographs from the 1930s were used as the basis for a digital reconstruction of the Bloomstrandbreen glacier (Geyman et al., 2022). Small inset shows the location of Kongsfjorden in Svalbard. Photo credit: Norwegian Polar Institute.

Kittiwakes have to adapt to climate change

Kittiwakes live naturally in colonies in the Arctic, often on steep mountain slopes. The name kittiwake was derived from its call, a shrill ‘kittee-wa-aaake, kitte-wa-aaake’. You can easily identify it from its black legs. The species is one of the most numerous seabirds, although recent surveys show that their population is decreasing rapidly.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature has listed the kittiwakes as vulnerable. How glacier retreat will affect the birds remains poorly known. It has been suggested that warmer ocean water will force the kittiwakes to fly further off the coast to find food, affecting their reproductivity. In northern Norway, they have started to adapt to climate change and become more urban. Kittiwakes now breed in greater numbers on buildings in Tromsø, steering a debate about their co-existence with humans.

Black-legged kittiwakes.

Photo credit: Geir Wing Gabrielsen/Norwegian Polar Institute.

Further reading

- New York Times: A Trove of Old Photos Could Reveal the Future of These Arctic Glaciers

- The Barents Observer: Climate refugees: Kittiwakes flee bird cliffs to resettle in urban spaces

- Cryoblog post: A wetter future for the Arctic

- Cryoblog post: Water plumes are tickling the Greenland Ice Sheet

Edited by Marie Cavitte

Katrin Lindbäck is a researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, Norway. She investigates the effect of climate change on the Cryosphere in the Arctic and Antarctica. She tweets as @polarkatten. Contact Email: katrin.lindback@npolar.no

Katrin Lindbäck is a researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, Norway. She investigates the effect of climate change on the Cryosphere in the Arctic and Antarctica. She tweets as @polarkatten. Contact Email: katrin.lindback@npolar.no