Perhaps the most enduring and important signal of a warming climate has been that the minimum Arctic sea ice extent, occurring each year in September, has declined precipitously. Over the last 40 years, most of the Arctic sea ice has thus been transformed to first-year ice that freezes in the winter and melts in the summer.

Concern about sea ice extent and area is valid: since sea ice is a highly reflective surface, a reduction of its area has a significant effect on the energy budget of Earth’s climate. Yet it is well-documented that, in the summertime, when sunlight is strongest, the biggest changes to sea ice volume are coming from effects not associated with changes to ice area, but with changes to sea ice thickness, like increased melt ponding. The change from thick, reflective multi-year summer sea ice to thin, ponded, less-reflective first-year ice are seen throughout the Arctic. In places like Nares Strait, the region of the Canadian Arctic that separates Canada from Greenland (seen above), commonly referred to as the “last ice area”, this is true as well.

The “Enduring Ice” Expedition

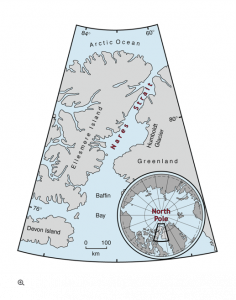

In the summer of 2016 and 2017, 4 filmmakers and a scientist (that’s me!) set out to examine Nares Strait, the area that separates Ellesmere Island in Canada from Northern Greenland (see map below). The Strait has been designated the “last ice area” by the World Wildlife Fund, a region which is expected to remain fully covered in thick sea ice even as the rest of the Arctic sea ice cover melts.

Yet when we arrived, what we found was anything but the promised land of thick, multi-year ice. Instead, all of the ice we encountered was thin, heavily ponded, and fragmented. In decades past, the presence of multi-year floes would dam Nares Strait, allowing ice-free passage for kayakers. Instead, the fractured ice poured through the strait, making passage impossible. Faced with an impassable strait, we resorted to pulling the kayaks over the land, moving a total of 100 km in 45 days.

Most projections have the Arctic totally ice-free in September by 2050, meaning there will truly be no multi-year ice left at all. Yet as the Arctic still cools dramatically in winter, during the summer months (from May to July) when solar radiation is highest, the total area of the Arctic covered in sea ice is still high, but now covered by thin first-year ice. At the same time, the ongoing warming has thinned the Arctic sea ice by more than half (Kwok, 2008).

The albedo of first year ice can be half or less that of multi-year thicker ice (Light, 2008). Since the Arctic has thinned substantially over the last 40 years, the consequences of this thinning on the Arctic and Earth climate system are dramatic.

More and more solar radiation is absorbed by thinner ice. Excess solar absorption leads to ocean and atmospheric warming, and to more sea ice melting, a process known as the ice-albedo feedback. It was previously thought that regions covered by sea ice where inhospitable to photosynthetic life. However, thinning sea ice is likely responsible for the increase in phytoplankton blooms in the Arctic, as more light is transmitted through the thinner ice.

The Arctic sea ice cover is rapidly transitioning from thick, multi-year ice to thin, ponded, first-year sea ice. As we can see, this thinning is resulting in a totally new Arctic climate system.

Further Reading

-

Image of the Week – The 2018 Arctic summer sea ice season (a.k.a. how bad was it this year?)

-

Image of the Week — Making pancakes

-

Image of the Week — Seasonal and regional considerations for Arctic sea ice changes

-

Image of the Week – The ups and downs of sea ice!

- Kwok, R., and D. A. Rothrock (2009), Decline in Arctic sea ice thickness from submarine and ICESat records: 1958-2008, Geophys. Res. Lett.

- Arrigo et. al., (2012), Massive phytoplankton blooms under Arctic sea ice, Science.

- Horvat, C., D. R. Jones, S. Iams, D. Schroeder, D. Flocco, and D. Feltham (2017), The frequency and extent of sub-ice phytoplankton blooms in the Arctic Ocean, Sci. Adv.

- Light, B., T. C. Grenfell, and D. K. Perovich (2008), Transmission and absorption of solar radiation by Arctic sea ice during the melt season, J. Geophys. Res. Ocean.

Edited by Violaine Coulon and Sophie Berger

Chris Horvat is a NOAA climate and global change postdoctoral fellow at Brown University in Providence, RI. He tweets as @chhorvat and you can also reach him on his website.

Chris Horvat is a NOAA climate and global change postdoctoral fellow at Brown University in Providence, RI. He tweets as @chhorvat and you can also reach him on his website.