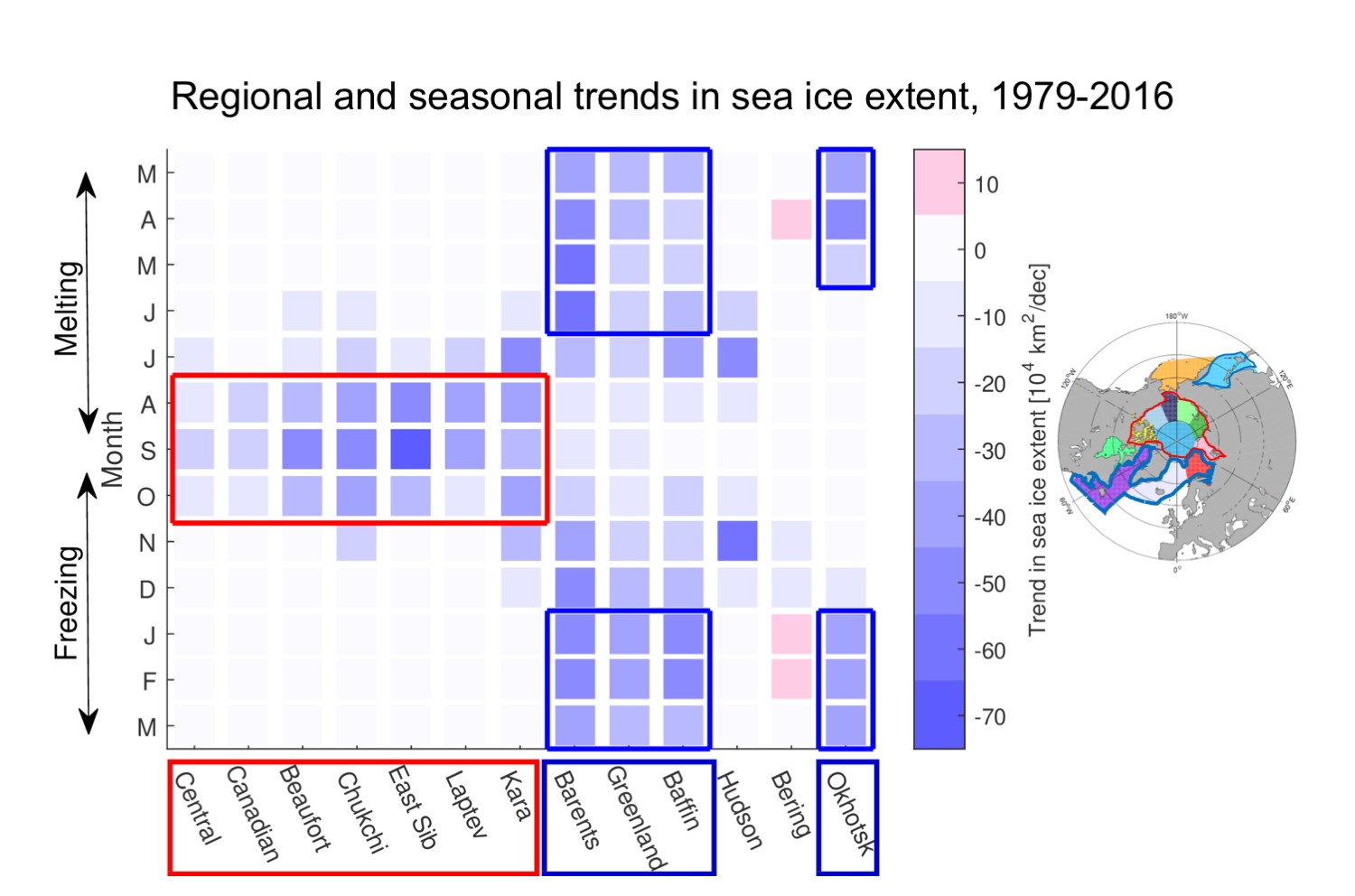

Monthly trends in sea ice extent for the Northern Hemisphere’s regional seas, 1979–2016. [Credit: adapted from Onarheim et al (2018), Fig. 7]

The Arctic sea ice is disappearing. There is no debate anymore. The problem is, we have so far been unable to model this disappearance correctly. And without correct simulations, we cannot project when the Arctic will become ice free. In this blog post, we explain why we want to know this in the first place, and present a fresh early-online release paper by Ingrid Onarheim and colleagues in Bergen, Norway, which highlights (one of) the reason(s) why our modelling attempts have failed so far…

Why do we want to know when the Arctic will become ice free anyway?

As we already mentioned on this blog, whether you see the disappearance of the Arctic sea ice as an opportunity or a catastrophe honestly depends on your scientific and economic interests.

It is an opportunity because the Arctic Ocean will finally be accessible to, for example:

- tourism;

- fisheries;

- fast and safe transport of goods between Europe and Asia;

- scientific exploration.

All those activities would no longer need to rely on heavy ice breakers, hence becoming more economically viable. In fact, the Arctic industry has already started: in summer 2016, the 1700-passenger Crystal Serenity became the first large cruise ship to safely navigate the North-West passage, from Alaska to New York. Then in summer 2017, the Christophe de Margerie became the first tanker to sail through the North-East passage, carrying liquefied gas from Norway to South Korea without an ice breaker escort, while the Eduard Toll became the first tanker to do so in winter just two months ago.

On the other hand, the disappearance of the Arctic sea ice could be catastrophic as having more ships in the area increases the risk of an accident. But not only. The loss of Arctic sea ice has societal and ecological impacts, causing coastal erosion, disappearance of a traditional way of life, and threatening the whole Arctic food chain that we do not fully understand yet. Not to mention all of the risks on the other components of the climate system. (See our list of further readings at the end of this post for excellent reviews on this topic).

Either way, we need to plan for the disappearance of the sea ice, and hence need to know when it will disappear.

Arctic sea ice decrease varies with region and season

In a nutshell, the new paper published by Onarheim and colleagues says that talking about “the Arctic sea ice extent” is an over simplification. They instead separated the Arctic into its 13 distinct basins, and calculated the trends in sea ice extent for each basin and each month of the year. They found a totally different behaviour between the peripheral seas (in blue on this image of the week) and the Arctic proper, i.e. north of Fram and Bering Straits (in red). As is shown by all the little boxes on the image, the peripheral seas have experienced their largest long term sea ice loss in winter, whereas those in the Arctic proper have been losing their ice in summer only. In practice, what is happening to the Arctic proper is that the melt season starts earlier (note how the distribution is not symmetric, with largest values on the top half of the image).

Talking about Arctic sea ice extent is an over simplification

Moreover, Onarheim and colleagues performed a simple linear extrapolation of the observed trends shown on this image, and found that the Arctic proper may become ice-free in summer from the 2020s. As they point out, some seas of the Arctic proper have in fact already been ice free in recent summers. The trends are less strong in the peripheral seas, and the authors write that they will probably have sea ice in winter until at least the 2050s.

So, although Arctic navigation should become possible fairly soon, in summer, you may need to choose a different holiday destination for the next 30 winters.

Melting summer ice. [Credit: Mikhail Varentsov (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)]

But why should WE consider the regions separately?

The same way that you would not plan for the risk of winter flood in New York based on yearly average of the whole US, you should not base your plan for winter navigation from Arkhangelsk to South Korea on the yearly Arctic-wide average of sea-ice behaviour.

Scientifically, this paper is exciting because different trends at different locations and seasons will also have different consequences on the rest of the climate system. If you have less sea ice in autumn or winter, you will lose more heat from the ocean to the atmosphere, and hence impact both components’ heat and humidity budget. If you have less sea ice in spring, you may trigger an earlier algae bloom.

As often, this paper highlights that the Earth system behaves in a more complex fashion that it first appears. Just like global warming does not prevent the occurrence of unpleasantly cold days, the disappearance of Arctic sea ice is not as simple as ice cubes melting in your beverage on a sunny day.

Reference/Further reading

Bhatt, U. S., et al. (2014), Implications of Arctic sea ice decline for the Earth system. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res., 39, 57-89

Meier, W. N., et al. (2014), Arctic sea ice in transformation: A review of recent observed changes and impacts on biology and human activity. Reviews of Geophysics, 52(3), 185-217.

Onarheim, I., et al. (2018), Seasonal and regional manifestation of Arctic sea ice loss. Journal of Climate, EOR.

Post, E., et al. (2013), Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline. Science, 341, 519-524

Edited by Sophie Berger