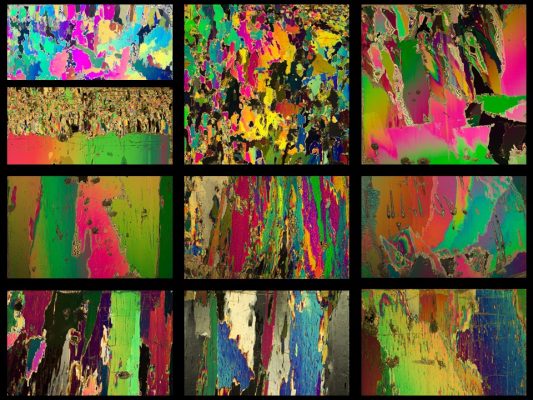

The Oscars 2018 might be over, but we have something for you that is just as cool or even cooler (often cooler than -20°C)! Our Image of the Week shows thin sections of sea ice photographed under polarized light, highlighting individual ice crystals in different colors, and is taken from a short video that we made. Read more about what this picture shows and watch the movie about how we got these colorful pictures…

Sea ice can vary in salinity

Sea ice forms differently than fresh water ice due to its salt content. When sea water begins to freeze, the ice crystals aren’t able to incorporate salt into their structure and hence reject salt into the surrounding water. This increases the density of the remaining sea water which sinks (see this previous post). Some salty water gets trapped between the crystals though. This water will also slowly freeze, always rejecting the salts into the remaining water. The saltier the water, the lower its freezing point. This means the remnant very salty water, which we call brine, remains liquid even at temperatures below -20oC!

Sea ice crystals can vary in shape

The first layer of sea ice is typically granular – the crystals are small and round, with a diameter around one centimeter. This is because this layer is formed in open seas, where the crystals which go on to form this layer are spun and broken up by surface waves. This granular structure includes lots of ‘pockets’ of trapped brine. Under this surface ice layer, which is typically 10-30 cm thick, ice starts growing in more sheltered conditions. Such sea ice is columnar. The crystals are flat and elongated – like layers in a vertical cake. The brine is trapped between these layers in brine channels. When ice is relatively warm, for example shortly after freezing or before it starts melting, such channels are wide and can be connected. Brine can then escape from them at the lower end into the ocean. The channels also allow small, hardy microscopic plants and animals to travel through the ice. Often air bubbles are trapped in them too.

Sea ice can vary in how it looks too!

The size and form of sea ice crystals – sea ice texture – impacts various properties of the sea ice including its salt content, density and suitability as a habitat. It also influences the optical properties of ice, however. While pure water ice is transparent (see this previous post), sea ice appears milky. That is because of brine channels and bubbles between the crystals.

When looking at large regions of sea ice from space by sensors mounted on satellites, sea ice texture will be important too. Visible light has a short wavelength and this means it only penetrates into the top millimeter of ice. Images collected in the visible light range (see this previous post) will show features dominated by the surface properties of the ice. In comparison, microwaves have a longer wavelength and can penetrate deeper into the ice. Hence imagery of the sea ice cover collected in the microwave spectrum of light (see this previous post) will display features influenced by the internal structure of the sea ice in addition to the surface features.

The video below shows how the sea ice samples are analyzed for texture and how we got the colorful pictures for our Image of the Week…

Further reading

- Image of the Week – Our salty seas and how this affects sea ice growth

- Image of the Week – Getting glaciers noticed!

- Image of the Week – Sea Ice Floes!

- Image of the Week – What’s up with the sea-ice leads?

Edited by Adam Bateson and Clara Burgard

Polona Itkin is a Post-doctoral Researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute, Tromsø. She investigates the sea ice dynamics of the Arctic Ocean and its connection to the sea ice thickness. In her work she combines the information from in-site observations, remote sensing and numerical modeling. Polona is part of the social media project ‘oceanseaiceNPI’ – a group of scientists that communicates their knowledge through social media channels: Instagram.com/OceanSeaIceNPI, Twitter.com/OceanSeaIceNPI, Facebook.com/OceanSeaIceNPI, contact Email: polona.itkin@npolar.no

Polona Itkin is a Post-doctoral Researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute, Tromsø. She investigates the sea ice dynamics of the Arctic Ocean and its connection to the sea ice thickness. In her work she combines the information from in-site observations, remote sensing and numerical modeling. Polona is part of the social media project ‘oceanseaiceNPI’ – a group of scientists that communicates their knowledge through social media channels: Instagram.com/OceanSeaIceNPI, Twitter.com/OceanSeaIceNPI, Facebook.com/OceanSeaIceNPI, contact Email: polona.itkin@npolar.no

vijai shankar

Awsome images Dr.Polona. Amazing work.