Going on a cruise for a month sounds tempting for most people and that is exactly how I spent one month of my summer. Instead of sunshine and 25 degrees, the temperature was closer to the freezing point on the thermometer and normal summer weather was replaced by milder weather conditions. The destination of the cruise was the western Nordic Sea and the east Greenland Margin. The ice2ice cruise was not a regular cruise, but a scientific cruise, starting in Reykjavik then heading towards the east coast of Greenland and ending in Tromsø, Northern Norway. Without the option to go ashore and far away from civilization, I spent four weeks aboard the Norwegian RV G.O. Sars. When I came home from the middle of the ocean, I realized that I had been part of a unique project.

The ice2ice cruise logo, where the red dots indicate the more than 30 sites of coring marine sediments under the ice2ice cruise. Photo credit: Amandine Tisserand

Why are climate scientists going on a cruise?

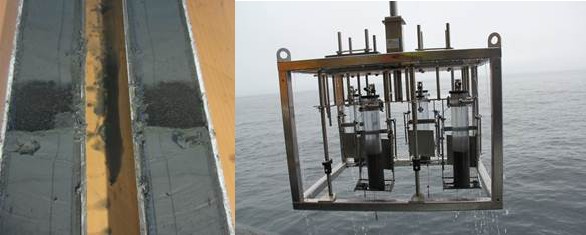

The purpose of the cruise was to collect marine sediment cores in the western Nordic Seas and along the east Greenland Margin. The retrieved sediments can be used to document abrupt changes in sea ice cover and ocean circulation along the East Greenland continental margin, during glacial times and for the more recent past. For this purpose three different sediment coring systems were used. The multicore, which samples sediments, including the sediment/water interface at the sea floor, the gravity core that is used to get information about the deeper marine sediments (up to 5 meter), and the calypso core that could retrieve up to 20 m long sediment cores, containing muddy sediments from the ocean floor to the ship’s deck.

One of the main questions of the ice2ice project is why there are abrupt climate changes. The sediment cores should be ideal for correlation to the RECAP (http://recap.nbi.ku.dk/) ice core from Renland Ice Cap in Eastern Greenland, drilled earlier this year. Together it is a unique material, which hopefully can bring information of the sea ice cover and its extent back in time.

Sediments: a split calypso core showing a clear pattern of a tephra layer from a volcanic eruption (left), and the multicore on the way up with four successful sediment cores (right). Photo credit: Iben Koldtoft and Ida Synnøve Olsen.

When everything is new – also the type of cruise

This was my first cruise ever, and before I boarded the ship in Reykjavik in mid-July, my knowledge of marine sediments and the ocean was very limited. Most of the people on board the ship were geologists who knew a lot about sediments from the ocean and had been on cruises before. Now a month later, my knowledge about sediments and the life aboard a research ship has become much larger. I think I had the steepest possible learning curve about sediments, because there were no stupid questions to ask, and everyone was very nice about answering questions, even if it was outside their area. Usually I work with ice cores and modelling of glacier ice and for me everything was new. This meant that I could contribute with knowledge about the RECAP ice core instead. Now I can take part in a conversation about sediments together with other geologist.

Normally when going on a cruise, there are only a few scientists on board on the ship. This means that there is only time to core the sediments and cut them into sections, while all the scientific work takes places later, when the sediments are in the lab. On this cruise, as something new, we were several scientists, so when the sediments were on deck, we immediately did a splendid job of handling the cores, describing and analysing the material. Thus, the detailed lab analyses can start right away after the material gets back to Bergen.

Shipboard analyses indicated that the material we have brought back to the laboratories in Bergen covers a time span from the present and probably a few hundred thousand years back in time. Not all the data have been analysed yet but we are looking forward to start and we are eager to see the results.

The science

During the one month long cruise, we had collected numerous samples of shells from the ocean floor from 32 stations west of Iceland. We did CTD (Conductivity, Temperature and Depth) measurements, to get information about how the temperature, salinity, density and oxygen content of the water vary in the ocean, and we collected water samples at different depths to analyse oxygen and carbon isotopes. We also collected sediments from 31 stations and every core has passed the DNA sampling, color and MS measurements stations. The cores were then cut into sections, split down through the middle, logged and described so that we could get an initial feel for the quality and utility of the samples we retrieved, before they are brought to shore for much more detailed analysis.

Ashley, Margit and Ida cut a gravity core into sections (left), while Alby brings a multicore from the deck down to the lab (right). Photo credit: Dag Inge Blindheim and Kerstin Perner.

Working 24-hour shifts on the ship meant that we achieved a lot and we brought home more than 200 m of muddy sediment cores from the sea floor from the western Nordic Seas and the east Greenland Margin and more than 190 water samples.

Although it was 12 hours of hard work most of the days, it was a pleasure to be part of the cruise. It has certainly not been my last cruise, if it is up to me, and I will look forward to a new cruise if I am lucky enough to get the chance. Weather was nice most of the time, but of course, we had some days of rough seas. The professionalism of the crew of G.O. Sars created an excellent atmosphere for work and time off, it was more like being on a real 4 star cruise if we ignore the time we worked.

Henrik is taking DNA samples of a gravity core (left) and water samples from the CTD (middle). Photo credit: Iben Koldtoft. I am happy after having packed one of the last sediment sections, which is now ready to be sent to Bergen and further analyzed (right). Photo credit: Kerstin Perner

On the ice2ice cruise the scientists were Eystein, Carin, Jørund, Dag Inge, Bjørg, Christian, Margit, and Amandine from Uni Research (Uni Research Climate, Norway), Stig, Sarah, Evangeline, Henrik, Ashley, and Ida from UiB (University of Bergen, Norway), Flor from GEUS (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Denmark), Mads from CIC (Centre for Ice and Climate, Denmark), Kerstin from IOW (Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, Germany), Albertine from Bris. (University of Bristol, UK), and myself Iben from DMI & CIC (Danish Meteorological Institute & Centre for Ice and Climate, Denmark). We were 19 participants, 8 men and 11 women, representing 8 different nationalities, and supported by a ship crew of 15. We were in good spirits all the time and a successful cruise!

The cruise would not be possible without support from the European Research Council Synergy project ice2ice (Danish-Norwegian), Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research (Norway) and Institute of Marine Research (Norway), who provided research vessel and crew onboard.

You can read more about the ice2ice project on its homepage https://ice2ice.b.uib.no/

Iben Koldtoft is PhD student within the ice2ice project at Danish Meteorological Institute and Centre for Ice and Climate, University of Copenhagen, Denmark and supervised by Jens H. Christensen and Christine S. Hvidberg. She is interested in modelling the dynamics of the Greenland Ice Sheet and the smaller glacier, Renland Ice Cap, in the Scoresbysund Fjord, Eastern Greenland. Currently she is coupling the ice sheet model PISM to the ocean by implementation of calving to the model. Surface mass balance simulations of the Greenland Ice Sheet will later be used to assess the quality of the interaction between the ice sheet model and a climate model in comparison to observations.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Did you know… about the fluctuating past of north-east Greenland?