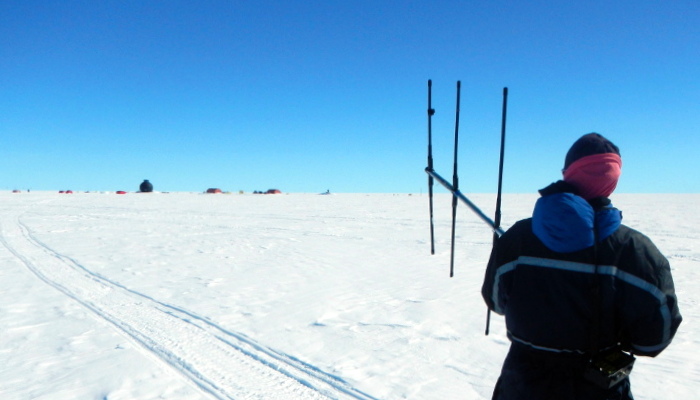

When working in the middle of an ice sheet, you rarely get to experience the amazing wildlife of the polar regions. So what are we doing hundreds of kilometres from the coast with an animal tracker device? We are listening to the snow of course! It is not crazy; It is what Image of the Week today is all about!

Going Wireless

![E. Bagshaw testing the range of an ETracer in a 12m borehole at the bottom of a 2m deep snow pit. [Credit: N. B. Karlsson].](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2016/10/liz_egghole-300x225.jpg)

E. Bagshaw testing the range of an ETracer in a 12m borehole at the bottom of a 2m deep snow pit. [Credit: N. B. Karlsson].

In June 2016, Liz Bagshaw and I travelled to the EGRIP (East Greenland Ice Core Project) camp to test a handful of wireless sensors named “ETracers” in a new setting. The “wireless” part is very important, because it means that we can make measurements without having to connect our instrument to a cable, which may fail or snap. Instead, the sensors transmit all their data as radio waves. We use the same frequency that biologists use for tracking animals – although there weren’t many to see in the middle of the Greenland Ice Sheet!

The ETracer sensors were originally developed for measuring the meltwater under the ice at the margin of the Greenland ice sheet. We wanted to test if they could also tell us something about what is going on in the snow. For example, how does the snow temperature change and how is the snow compacting in different parts of the ice sheet? These questions might seem theoretical but their answers are important when working with data from satellites, since the satellite measurements may be affected by different snow conditions.

Pink Baubles

![The ETracers stacked on small magnets. This temporarily stops their bleeps [Credit: E. Bagshaw].](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2016/10/etracers-300x200.jpg)

The ETracers stacked on small magnets. This temporarily stops their bleeps bleeps and is an efficient way of silencing them while we are listening for other ETracers [Credit: E. Bagshaw].

Our colleagues had also drilled several 12m boreholes for us, and we now installed ETracers at the bottom of the holes as well as on the surface. For over a month, the ETracers sent back information to our receivers on the ground about temperature, pressure and conductivity of the snow.

We are still analysing our data but the most important part of our work is done: we have shown that the ETracers can accurately measure the properties of the snow. Next year, we will return to the camp and set up more experiments. Stay tuned – or rather keep listening!

You can read more about setting up the EGRIP camp in a previous Image of the Week post “Ballooning on the Ice“.

Edited by Emma Smith and Sophie Berger