A few month ago, we were taking you on a trip back to Antarctic fieldwork 50 years ago, today we go back to Greenland during 1930s!

When geopolitics serves cryospheric sciences

The Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague awarded Danish sovereignty over Greenland in 1933 and besides geopolitical interests, Denmark had a keen interest in searching for natural resources and new opportunities in this newly acquired colony. In the 1930s the Danish Government initiated three comprehensive expeditions; one of these, the systematic mapping of East Greenland, was set off by The Greenlandic Agency, The Marines’ air services, The Army’s Flight troops and Geodetic Institute. The Danish Marines provided pilots, mechanics, and three Heinkel seaplanes.

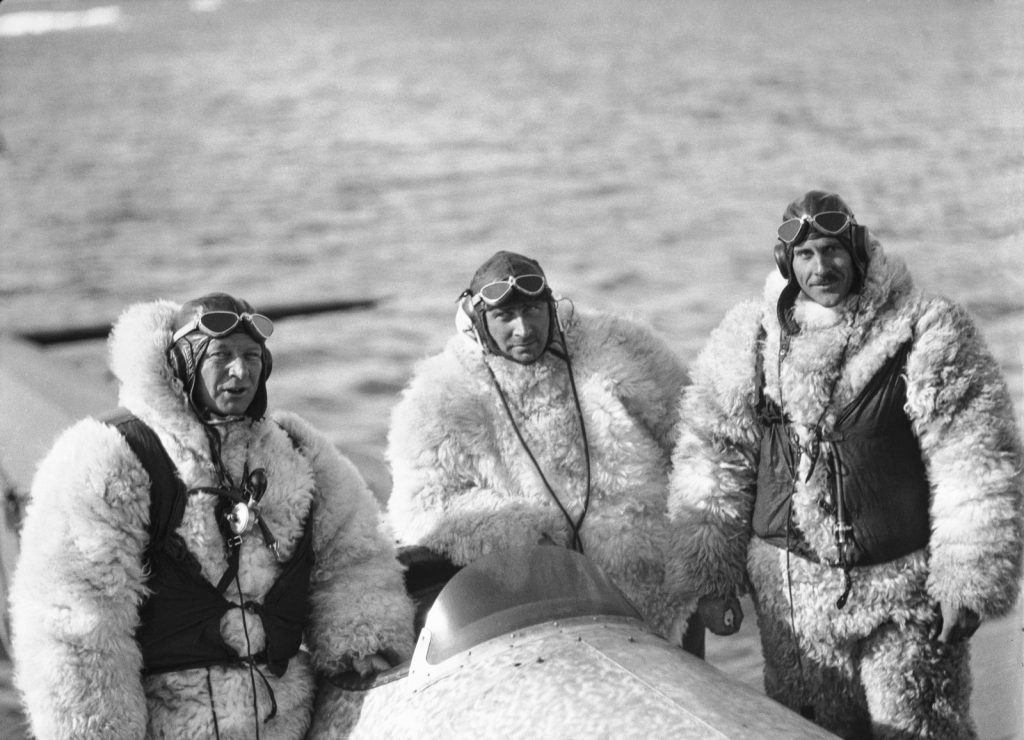

Danish expeditioner Lauge Koch, centre, along with his pilots all dressed in suits made from polar bear. (Credit: The Arctic Institute)

Aerial photography in the 1930s – practical constraints

The airplanes had three seats in an open cockpit. The pilot was seated in the front, the radio operator in the center and in the back the photographer – this seat was originally for the machine-gun operator.

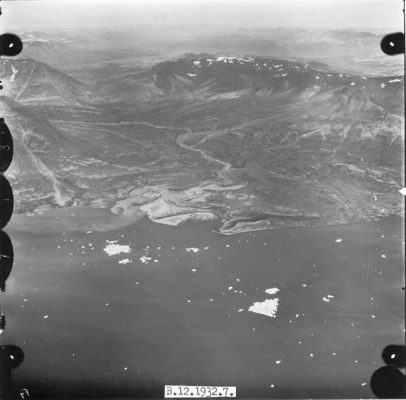

At the outset, the idea was to take vertical images, but that was impossible at the time due to the height of the mountains and the limited capability of the aircraft to reach adequate heights. The airplanes couldn’t reach more than 4000 m – similar to the height of mountains in Greenland. Oblique images were therefore recorded. The reduced view of the terrain when photographing in oblique angles required many more flights than originally planned. The photographic films were processed immediately after each flight. 45,000 km were covered during the first season, which lasted about two and a half months. In the following years, each summer a flight covered parts of the Greenlandic coast. During the Second World War, the mapping was temporarily stopped due to safety reasons.

The aircraft had an open hole in the floor for the photographer, originally where the machine gunner would sit.(Credit: The Arctic Institute)

An unexplored treasure trove of climate data

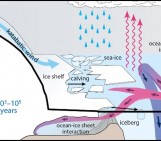

The tremendous volume of aerial images obtained from several expeditions and hundreds of flights not only constitutes the cornerstone of mapping in Greenland, but is invaluable data for studying climate change in these remote regions. The 1930s survey, compared to modern imagery, provides crucial insight into coastal changes, ice sheet mass balances, and glacier movement. Glacier fluctuations in southeast Greenland have been identified, showing that many land-terminating glaciers underwent a more rapid retreat in the 1930s than in the 2000s, whereas marine-terminating glaciers retreat more rapidly during the recent warming (Bjørk et al, 2012).

An ongoing project between the University of Copenhagen, INSTAAR (Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research) in Boulder, Colorado, and Natural History Museum of Denmark is currently focusing on analysing deltaic changes in Central and Southern Greenland; linking shoreline development to climate changes – these historic aerial images are essential for detecting such coastal evolution. However, there are still many other links between the past and present climate to be discovered from these images. Interested in hearing more about the project or the aerial images? Please contact Mette Bendixen (mette.bendixen@ign.ku.dk)

Bibliography

Bjørk, A. A., Kjær, K. H., Korsgaard, N. J., Khan, S. A., Kjeldsen, K. K., Andresen, C. S., … & Funder, S. (2012). An aerial view of 80 years of climate-related glacier fluctuations in southeast Greenland. Nature Geoscience, 5(6), 427-432. http://dx.doi.org/DOI:10.1038/ngeo1481

Edited by Alistair McConnell, Sophie Berger and Emma Smith

Mette Bendixen is s a PhD student at the Center for Permafrost in Copenhagen. She investigates the changing geomorphology of Greenlandic coasts, where climate changes can have huge impact on the local environment.

Mette Bendixen is s a PhD student at the Center for Permafrost in Copenhagen. She investigates the changing geomorphology of Greenlandic coasts, where climate changes can have huge impact on the local environment.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Polar Exploration: Perseverance and Pea Sausages

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | For dummies – About ice sheet models and their cold relationship to climate models