This month’s GeoPolicy Blog post features the Competence Framework ‘Science for Policy’ for researchers developed by the European Commission Joint Research Centre (JRC). This newly developed framework introduces the different competences scientists can collectively build to increase their policy impact, and how it can be used by research institutions and organisations. Throughout this post, Policy Analyst Lene Topp provides insights into key features and aspects of the Frameworks functionality that she was the lead author on.

The Competence Framework ‘Science for Policy’ for researchers

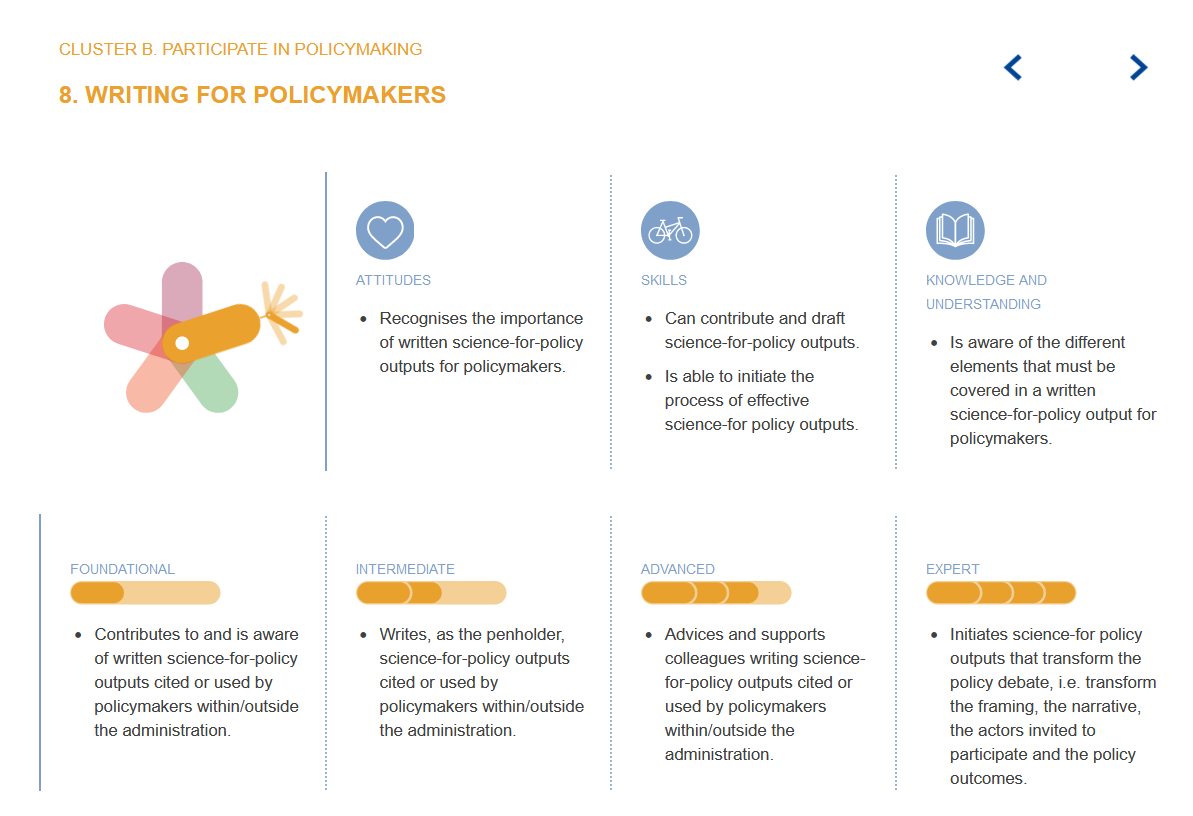

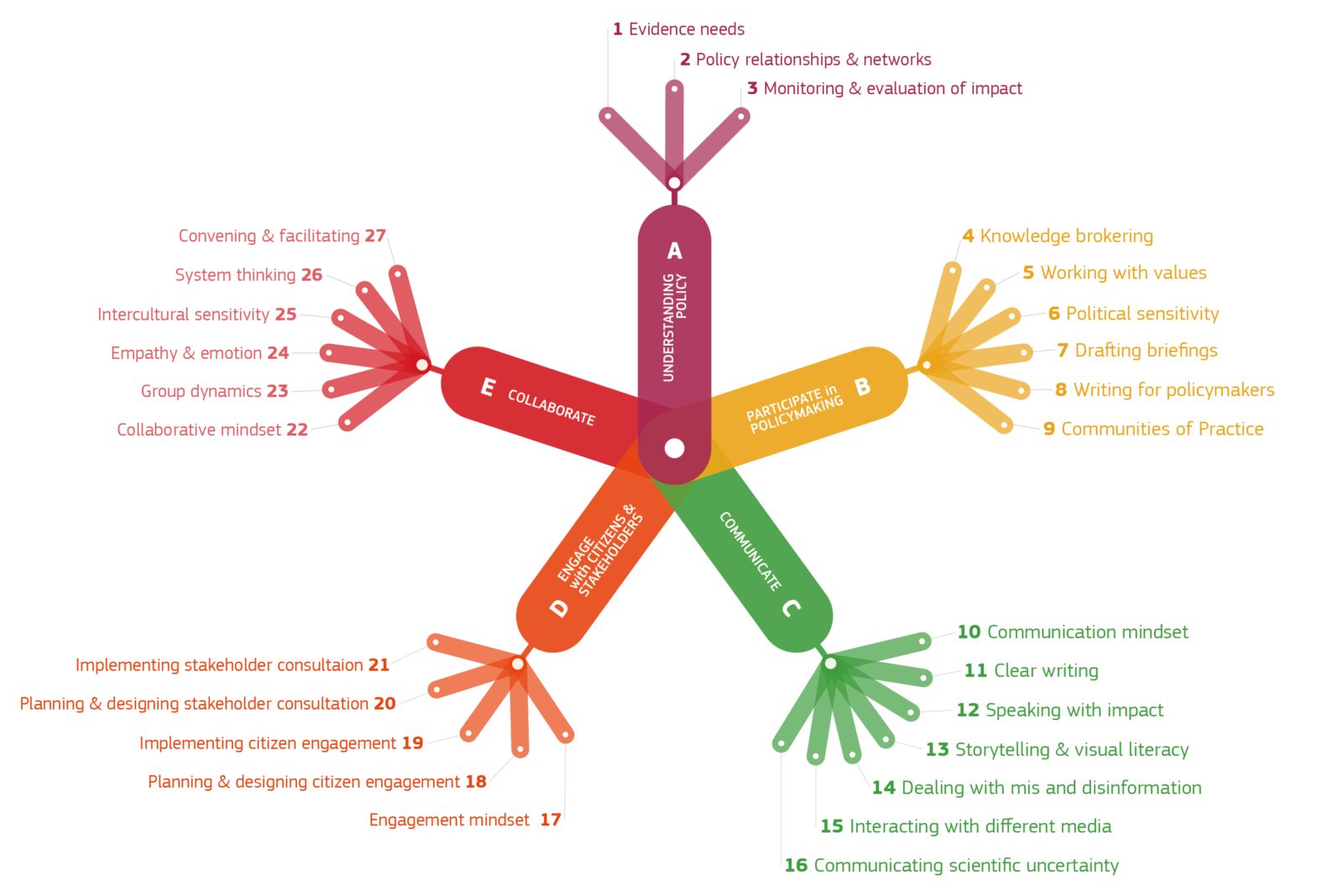

There is a growing need to integrate scientific information into the policymaking process with many of today’s key issues becoming increasingly more interconnected and complex. While many researchers would like to support this information-need, effectively engaging with the policymaking process and achieving policy impact requires a distinct set of competences that are rarely covered in formal university education or doctoral programmes. The JRC’s Competence Framework ‘Science for Policy’ for researchers outlines 27 different competences that researchers and organisations can develop to connect with decision-makers, provide relevant, robust and timely information, and effectively create policy impact. These competences aim to foster ‘Science for Policy’ capacities among researchers and are grouped in 5 competence clusters: Understanding policy, Participating in policymaking, Communication, Engage with citizens and stakeholders, and Collaborate. While it would be fantastic if we could all become experts in each competence, Topp emphasizes that achieving policy impact is not an individual but a team effort,

We are not advocating for researchers to become super-human, e.g. being an expert on implementing citizen engagement activities, writing policy briefs, dealing with mis and dis information. Rather this is something that a research organisation or a department in it collectively achieve. Therefore, the competence framework presents the collective set of competences for policy impact required by an organisation or a sub-unit in it.

The 5 clusters and 27 competences within the JRC’s Competence Framework ‘Science for Policy’ for researchers

Each competence includes four progression levels, from foundational to expert level. This enables individual researchers to self-assess their perceived level across all 27 competences and organisations to map their team’s competence strengths and weaknesses. Each competence also outlines associated attitudes, skills, and knowledge that is required to move through to its advanced and expert levels. Topp stresses, that to achieve policy impact the best available knowledge and the right skills to present evidence to policymakers, must be accompanied by the appropriate attitudes, e.g. empathy, collaborative mindset, Thus, to progress from one level to the next, the additional skills, knowledge and attitudes required go hand and in hand.

The integration of science into the policymaking process is, of course, also dependent on policymakers. With increasing complex political challenges, it’s vital that institutions such as the European Commission continue to build on innovative approaches to policymaking and further strengthen strategic foresight, co-creation, and the culture of evidence-informed policymaking. The ‘Innovative Policymaking’ Competence Framework was created to support this. Consisting of a total of 36 competences divided into 7 clusters, it promotes co-creation and the integration of scientific evidence into policy design.

How can scientists use the Competency Framework?

The Competence Framework ‘Science for Policy’ for researchers was created through an iterative process that not only focuses on the ‘what’ but also on the ‘how’. It provides insights, guidance, and a sense of how to progress on various competences. While it was developed by the European Commission, it was deliberately designed to be easily adapted to meet the needs of those using it regardless of the location or focus area. The Framework therefore has the potential to be used across scientific disciplines and geographical areas.

Self-assessment: Individuals and Teams

Organisations can design self and team assessments based on the competence descriptors and learning outcomes per proficiency level. Once your team has undertaken a self-assessment, you can identify the competences that have a lower proficiency level and decide what areas you would like to improve. Furthermore, understanding the teams strengthens can be support the establishment of individual and team goals as well as the overarching strategic aim of your policy engagement. Topp also highlighted that the assessment tool, which is expected to be released in early 2023, will provide individuals and organizations with the possibility to define their level of ambition for each of clusters of competences. She continued,

This is to stress that individual researchers are not expected to excel in all competences, but also that depending on the context they are operating, researchers or research organizations may determine what competences and at what proficiency level would be appropriate for them to achieve policy impact. And by the way, this is very likely to vary over time.

Strategically growing your team

The Competence Framework and self-assessment tool can also be used during the hiring process to find a new team member who would complement your team’s current competences and fill existing deficiencies. Identifying key competences that your team is lacking and developing position description with these in mind may help you to invite and hire a suitable candidate.

Selecting policy projects that play to your strengths

Understanding the collective competences of your team could help you to define the types of policy projects that you would collectively excel in and assign key responsibilities taking into consideration the competences of the individual team members. While there are many factors that should be considered when selecting a project, making strategic decisions by playing to your team’s strengths may help you to achieve a better outcome or result. Topp gives the example,

For a policy brief to have impact, you need not only have succinct writing skills, but also storytelling and visual presentation skills, knowledge about political landscape as well as acknowledging the importance of listening to politicians, policymakers, stakeholders and citizens to catch the pulse of the debate and become aware of dominant values in play and political sensitivities.

Developing education and training programmes

The Competence Framework has the potential to be incredibly useful for educators and workshop trainers. The clusters or individual competences could be used to guide specific modules within a training course, to identify learning outcomes, as a basis for certification schemes, and to define career progression pathways. The Framework was designed to support training programmes across different formats and could therefore be incorporated into both shorter and longer lessons and across formats (classroom, online or self-paced e-learning).

Starting a conversation

If you’re working within a scientific organisation or research institute and would like to start engaging more in the policymaking process, you may consider to start a conversation in your team about the Competence Framework and the competences, i.e.. knowledge, skills and attitudes, that you and your team would like to develop. The Competence Framework is not only a great visual representation of the different competences researchers can develop, but also the areas in which they and their teams can engage. The Framework could help start a conversation about the different areas those in your team find important and how they could be integrated into your work.

Personal Development

During the EGU22 session The role of scientific institutions in policymaking, Topp shared a Padlet of the 27 competences and asked participants to select the three competences they would most like to develop. Understanding the competences that you are personally interested in developing can help you to define the work, activities, opportunities, and trainings that you would like to engage in or move towards. The Padlet from the EGU22 session is still open for you to mark your preferences and see the competences that others have selected.

I know what competences I’d like to develop – what now?

There are fantastic resources out there for scientists to develop their skills, attitudes, and knowledge and to level-up their competences. The JRC’s Science for Policy Handbook is a great place to start. There are sections within the Handbook that relate to many, if not all, of the 27 competences. The JRC also provide a 1-hour interactive e-learning course on Science for Policy and how to maximize your policy impact. There are also numerous resources available on the policy section of the EGU website and you can subscribe to the EGU’s Science for Policy Newsletter to get more information about about upcoming science for policy opportunities and activities.

But of course, the best way to learn about something is by doing it! Engaging in policymaking processes and activities will also help you and your team to develop competences. This blog post highlights the 5 ways for scientific institutions to support European policymaking for those working in institutions but who aren’t sure where to start. If you’re not currently part of a team, you may want to start networking with others who are also interested in engaging. The JRC’s Knowledge for Policy Platform is both a great place to find relevant resources and connect with others who are working on the science-policy interface. Working Groups are another way of meeting those working on the interface and gaining some experience working on policy-relevant topics. The EuroScience’s Science Policy Working Group is a good option and is currently accepting new members.

Further reading: Competences for Policymaking: Competence Frameworks for Policymakers and Researchers working on Public Policy