The recent European Parliament election illustrated how divided Europe has become politically and intergenerationally. While the established parties lost their ground, both far-right populistic, anti-EU and liberal, green pro-EU parties grew in popularity among voters1, with the younger generation favoring the latter and the generations above the former2. What role is there for science in this divided landscape? Climate scientists Daniel Price and Erlend Moster Knudsen established an outreach campaign, Pole to Paris, to break down barriers and create dialogues on climate change with a broad audience from all corners of the Earth. The discoveries they made from this initiative were published recently in EGU’s new open access journal Geoscience Communication.

To build bridges in a divided terrain, our recently published paper makes a strong case for the importance of science communication training. In this publication3, we argue that the politicisation[i] and polarisation[ii] of climate change over the last decades call for a new role for climate scientists, in which scientists more actively engage with society at large. The role of the ‘pure scientist’, one that generates facts without consideration for its usage or users, is outdated, and the need for the ‘science communicator’ and the ‘honest broker of the policy alternatives’4 is rising. The time has come for climate scientists to offer expert interpretation of climate science and draw attention to its implications.

Just how is the key.

In the paper, we suggest five key components for successful science communication with non-academic audiences. Discussed in more detail in the publication, these are relevance, listening, positivity, perseverance and passion. They derive from our experience with science communication in 45 countries, through 10 languages, to audiences from three to 90 years old, within a wide range of societal groups. This experience comes from giving workshops on climate science, acting in a theatre play on climate skepticism, producing a biodiversity documentary, being a TV spokesperson on climate issues and writing two comic books on climate change and biodiversity loss, but – more importantly – from the 3000-km run and 10,000-km bike ride outreach campaign called Pole to Paris.

In the 7.5 months leading up to the climate summit COP 215 in Paris 2015, we were part of the climate awareness campaign Pole to Paris6. This outreach project focused on reshaping the way climate scientists engage with the public on climate change issues. Instead of communicating pure scientific facts, Pole to Paris highlighted the human faces of climate change. We did so by leaving our academic offices, running and cycling across half the globe, from Earth’s polar regions to Paris, to interact with a wide range of audiences along the way and through traditional news outlets and social media. Along the way, we carried with us flags from the Arctic and the Antarctic, symbolizing the global significance of climate change near the poles, and in a sense bringing these regions closer to the people.

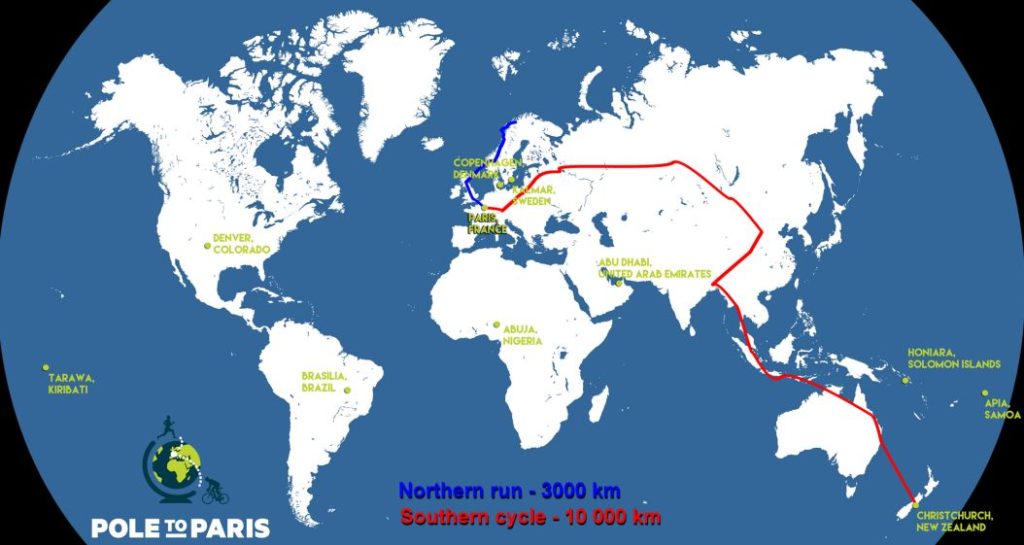

Map of the two Pole to Paris journeys: the Northern Run (blue trajectory) and the Southern Cycle (red trajectory). Also included

are the Global Voices events organized in collaboration with the partner United Nations Development Programme (green dots). Credit: E. M. Knudsen and O. J. de Bolsée 2019.

It was fundamental to the journeys that we engaged an audience not normally reached by scientific messages. Dan and I, two climate scientists with PhDs in Antarctic and Arctic climate change, respectively, led these journeys, which contributed to this goal, but there was more to the picture than just a one-way communication from the bike saddle and running shoes. To create a two-way interaction, we strove to use a familiar language and a known format in their home forums. Moreover, by establishing these dialogues, we were lucky to hear their own personal experiences of a changing environment.

As climate scientists, we are more used to talk in scientific terms like 2°C and 450 ppm, but human stories of climate change connect on a whole different level with laypeople. We therefore retold these stories at the open events and educational institutions along the way, and we shared them in traditional news outlets and social media. Overall, we estimated that the latter gave us a reach of more than 1 million people. Through video analyses and a follower survey, we propose that the inspirational messages of climate action by a younger generation were among the key reasons for this reach. Our 10 team members were all in our 20s, possibly explaining why we were especially successful in reaching other millennials and the Generation Z.

Left photo: Hundreds of cyclists joining Daniel Price for a morning ride in Jakarta, Indonesia. Right photo: Group run with Erlend Moster Knudsen in Trondheim. Credit Paul Kopperud/Tekna

Messages of climate action from climate scientists, however, can be problematic, as they question our objectivity. Our professional credibility as scientists, as defined by Nordhagen et al. (2014)9, comes from our peer-reviewed publication record, which scientific co-authors we collaborate with and what research institutions we are affiliated with. However, by advocating for positive personal and societal action on climate change, we moved beyond our core scientific base. Nevertheless, by making the problem tangible, concrete and possible to mitigate, climate change moves from something far away in space and time to something here and now. According to theories on science communication7,8, such actions do not foster climate denial, which was also our experience.

When doing outreach on a divisive topic like climate change, scientists need in any case to tread carefully to maintain their credibility as well as that of the scientific community. During Pole to Paris, we did so by avoiding partnerships with either side of the climate advocacy fringes and not favoring one political party over another. Instead, we partnered with scientific institutions and international organizations like the United Nations Development Programme and the World Meteorological Organization. By following these measures, along with giving talks and interviews, interacting with politicians and literally walking the talk, we experienced a boost in personal and public credibility, which altogether enhanced our overall researcher credibility.

Photo from a Pole to Paris open event in Kabelvåg, Lofoten Islands (Credit: Espen Mortensen)

Our experience supports suggestions published in a previous study10 that science participation and outreach can indeed rebuild the credibility among communities most critical of scientists. This is encouraging considering that post-factual societies have arisen in many parts of the world, from the US to Brazil and from Hungary to the Philippines, where a significant number of people accept an argument based on their emotions and beliefs rather than scientific facts. Fake news has become a threat to science, researchers and institutions alike, as highlighted at the 2019 EGU General Assembly11. Fostering constructive conversations about science and society, on the other hand, can improve decision-making, promote trust and credibility in scientific findings, and strengthen democratic processes12,13, ultimately counteracting the politicisation and polarisation of science and post-factual movements, respectively.

In our paper, we argue that the current training to become a scientist does not fulfill the position climate science and scientists has received in our daily discourse. To adapt to and play our new role as providers of trustworthy information of climate change, we argue that more emphasis should be placed on teaching researchers how to communicate science and interact with media, policymakers and pseudoskepticism, while less focus should be on the published record. This training will not only help narrow the widening gap between academia and the rest of society but, within academia, also provide better tools for teaching, mentoring, taking part in scientific discussions as well as contributing to better-written research proposals and journal publications.

As a scientific community, we will all benefit from reducing the politicisation and polarisation of climate change, depressing the breeding ground for post-factual movements, and acquiring tools to deal with a new generation of students angry about the older generations’ lack of climate action. Predominantly paid by taxpayers, we have a self-interest in providing recognizable services back to our society. Publishing an academic paper in scientific jargon being a paywall is not enough in itself. Rather, we need to better position ourselves through communication training to engage non-academic audiences in scientific facts about one of the biggest threats of our time: climate change.

By Erlend Moster Knudsen

You can learn more about the Pole to Paris campaign on their Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/poletoparis/

Erlend Moster Knudsen is a climate science researcher and communicator, currently working as a Senior Data Scientist for StormGeo in Bergen, Norway, and as the Deputy Director of Pole to Paris in Christchurch, New Zealand. He holds a PhD in Arctic climate dynamics from the University of Bergen. Erlend tweets at @ErlendMK

Erlend Moster Knudsen is a climate science researcher and communicator, currently working as a Senior Data Scientist for StormGeo in Bergen, Norway, and as the Deputy Director of Pole to Paris in Christchurch, New Zealand. He holds a PhD in Arctic climate dynamics from the University of Bergen. Erlend tweets at @ErlendMK

References

[i] Referring to how the science behind political decisions is increasingly promoted and attacked by advocates and opponents.

[ii] Referring to the growing division between elites, organizations and political parties viewing climate change as a negative consequence of industrial capitalism and those opposing such views.

- FRANCE 24: Populist push, green wave, establishment in turmoil: a round-up of the EU elections, France 24, 2019.

- Schminke, T. G.: How different generations voted in the EU election, Europe Elects, 2019.

- Knudsen, E. M., and de Bolsée, O. J.: Communicating climate change in a “post-factual” society: lessons learned from the Pole to Paris campaign, Geosci. Commun., 2, 83–93, doi:10.5194/gc-2-83-2019, 2019.

- Rapley, C., and De Meyer, K.: Climate science reconsidered, Nat. Clim. Change, 4, 745–746, doi: 10.1038/nclimate2352, 2014.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: COP 21, United Nations Climate Change, 2015.

- Price, D., Knudsen, E. M., Gillman, T., Willis, J., de Bolsée, O. J., Jones, C., Ward, B., Gustafson, J., Woodhouse, K.-S., Miao, W.: Pole to Paris, 2019.

- Witte, K.: Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model, Commun. Monogr., 59, 329–349, https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376276, 1992.

- Stoknes, P. E.: What we think about when we try not to think about global warming: Toward a new psychology of climate action, Chelsea Green Publishing, Vermont, USA, ISBN 978-1-60358- 583-5, 2015.

- Nordhagen, S., Calverley, D., Foulds, C., O’Keefe, L., and Wang, X.: Climate change research and credibility: balancing tensions across professional, personal, and public domains, Climatic Change, 125, 149–162, doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1167-3, 2014.

- Gauchat, G., O’Brien, T., and Mirosa, O.: The legitimacy of environmental scientists in the public sphere, Climatic Change, 143, 297–306, doi:10.1007/s10584-017-2015-z, 2017.

- Hill, C.: GeoPolicy: Fake news and populism – a threat to science in Europe, GeoLog, 2019.

- Wooden, R.: The principles of public engagement: at the nexus of science, public policy influence, and citizen education, Soc. Res., 73, 1057–1063, 2006.

- Nisbet, M.: Scientists in civic life: facilitating dialogue-based communication, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2018.