Much ink is spilled hailing the work of the early fathers of geology – and rightly so! James Hutton is the mind behind the theory of uniformitarianism, which underpins almost every aspect of geology and argues that processes operating at present operated in the same manner over geological time, while Sir Charles Lyell furthered the idea of geological time. William Smith, the coal miner and canal builder, who produced the first geological map certainly makes the cut as a key figure in the history of geological sciences, as does Alfred Wegener, whose initially contested theory of continental drift forms the basis of how we understand the Earth today.

Equally deserving of attention, but often overlooked, are the women who have made ground-breaking advances to the understanding of the Earth. But who the title of Mother of Geology should go to is up for debate, and we want your help to settle it!

In the style of our network blogger, Matt Herod, we’ve prepared a poll for you to cast your votes! We’ve picked five leading ladies of the geoscience to feature here, but they should only serve as inspiration. There are many others who have contributed significantly to advancing the study of the planet, so please add their names and why you think they are deserving of the title of Mother of Geology, in the comment section below.

We found it particularly hard to find more about women in geology in non-English speaking country, so if you know of women in France, Germany, Spain, etc. who made important contributions to the field, please let us know!

Mary Anning (1799–1847)

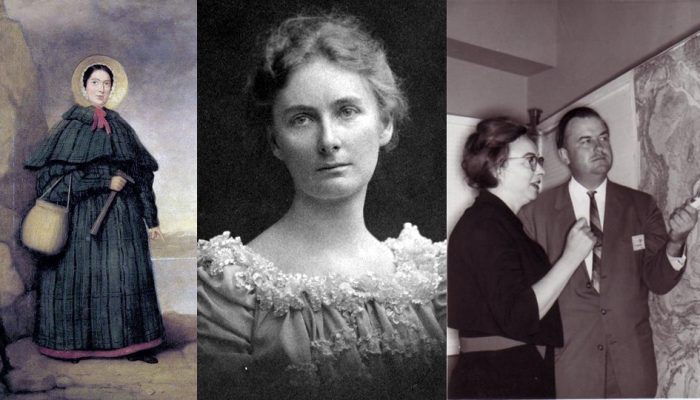

Mary Anning. Credited to ‘Mr. Grey’ in Crispin Tickell’s book ‘Mary Anning of Lyme Regis’ (1996).

Hailing from the coastal town of Lyme Regis in the UK, Mary was born to Richard Anning, a carpenter with an interest in fossil collecting. On the family’s doorstep were the fossil-rich cliffs of the Jurassic coast. The chalky rocks provided a life-line to Mary, her brother and mother, when her father died eleven years after Mary was born. Upon his death, Richard left the family with significant debt, so Mary and her brother turned to fossil-collecting and selling to make a living.

Mary had a keen eye for anatomy and was an expert fossil collector. She and her brother are responsible for the discovery of the first Ichthyosaurs specimen, as well as the first plesiosaur.

When Mary started making her fossil discoveries in the early 1800s, geology was a burgeoning science. Her discoveries contributed to a better understanding of the evolution of life and palaeontology.

Mary’s influence is even more noteworthy given that she was living at a time when science was very much a man’s profession. Although the fossils Mary discovered where exhibited and discussed at the Geological Society of London, she wasn’t allowed to become a member of the recently formed union and she wasn’t always given full credit for her scientific discoveries.

Charlotte Murchinson (1788–1869)

Roderick and Charlotte Murchinson made a formidable team. A true champion of science, and geology in particular, Charlotte, ignited and fuelled her husband’s pursuit of a career in science after resigning his post as an Army officer.

Roderick Murchinson’s seminal work on establishing the first geologic sequence of Early Paleozoic strata would have not arisen had it not been for his wife’s encouragement. With Roderick, Charlotte travelled the length and breadth of Britain and Europe (along with notable friend Sir Charles Lylle), collecting fossils (one of the couple’s trips took them to Lyme Regis where they met and worked with Mary Anning, who later became a trusted friend) and studying the geology of the old continent. Roderick’s first paper, presented at the Geological Society in 1825 is thought to have been co-written by Charlotte.

Not only was Charlotte a champion for the sciences, but she was a believer in gender equality. When Charles Lylle refused women to take part in his lectures at Kings Collage London, at her insistence he changed his views.

Florence Bascom (1862–1945)

By Camera Craft Studios, Minneapolis – Creator/Photographer: Camera Craft Studios, Minneapolis. Persistent Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives Collection: Science Service Records, 1902-1965 (Record Unit 7091)

Talk about a life of firsts: Florence Bascom, an expert in crystallography, mineralogy, and petrography, was the first woman hired by the U.S Geological Survey (back in 1896); she was the first woman to be elected to the Geological Society of America (GSA) Council (in 1924) and was the GSA’s first woman officer (she served as vice-president in 1930).

Florence’s PhD thesis (she undertook her studies at Johns Hopkins University, where she had to sit behind a screen during lectures so the male student’s wouldn’t know she was there!), was ground-breaking because she identified, for the first time, that rocks previously thought to be sediments were, in fact, metamorphosed lavas. She made important contributions to the understanding of the geology of the Appalachian Mountains and mapped swathes of the U.S.

Perhaps influenced by her experience as a woman in a male dominated world, she lectured actively and went to set-up the geology department at Bryn Mawr College, the first college where women could pursue PhDs, and which became an important 20th century training centre for female geologist.

Inge Lehmann (1888-1993)

There are few things that scream notoriety as when a coveted Google Doodle is made in your honour. It’s hardly surprising that Google made such a tribute to Inge Lehmann, on the 127th Anniversary of her birth, on 13th May 2015.

A Danish seismologist born in 1888, Inge experienced her first earthquake as a teenager. She studied maths, physics and chemistry at Oslo and Cambridge Universities and went on to become an assistant to geodesist Niels Erik Nørlund. While installing seismological observatories across Denmark and Greenland, Inge became increasingly interested in seismology, which she largely taught herself. The data she collected allowed her to study how seismic waves travel through the Earth. Inge postulated that the Earth’s core wasn’t a single molten layer, as previously thought, but that an inner core, with properties different to the outer core, exists.

But as a talented scientist, Inge’s contribution to the geosciences doesn’t end there. Her second major discovery came in the late 1950s and is named after her: the Lehmann Discontinuity is a region in the Earth’s mantle at ca. 220 km where seismic waves travelling through the planet speed up abruptly.

Marie Tharp (1920-2006)

That the sea-floor of the Atlantic Ocean is traversed, from north to south by a spreading ridge is a well-established notion. That tectonic plates pull apart and come together along boundaries across the globe, as first suggested by Alfred Wegener, underpins our current understanding of the Earth. But prior to the 1960s and 1970s Wegener’s theory of continental drift was hotly debated and viewed with scepticism.

Bruce Heezen and Marie Tharp with the 1977 World Ocean’s Map. Credit: Marie Tharp maps, distributed via Flickr.

In the wake of the Second World War, in 1952, in the then under resourced department of Columbia University, Marie Tharp, a young scientist originally from Ypsilanti (Michigan), poured over soundings of the Atlantic Ocean. Her task was to map the depth of the ocean.

By 1977, Marie and her boss, geophysicist Bruce Heezen, had carefully mapped the topography of the ocean floor, revealing features, such as the until then unknown, Mid-Atlantic ridge, which would confirm, without a doubt, that the planet is covered by a thin (on a global scale) skin of crust which floats atop the Earth’s molten mantle.

Their map would go on to pave the way for future scientists who now knew the ocean floors weren’t vast pools of mud. Despite beginning her career at Columbia as a secretary to Bruce, Marie’s role in producing the beautiful world ocean’s map propelled her into the oceanography history books.

Over to you! Who do you think the title of the Mother of Geology should go to? We ran a twitter poll last week, asking this very question, and the title, undisputedly, went to Mary Anning. Do you agree?

[polldaddy poll=9489734]

By Laura Roberts, EGU Communications Officer

All references to produce this post are linked to directly from the text.

EGU, the European Geosciences Union, is Europe’s premier geosciences union, dedicated to the pursuit of excellence in the Earth, planetary, and space sciences for the benefit of humanity, worldwide. It is a non-profit international union of scientists with over 12,500 members from all over the world. Its annual General Assembly is the largest and most prominent European geosciences event, attracting over 11,000 scientists from all over the world.

This text was edited on 1 Septmember 2016 to correct the spelling of Weger. With thanks to Torbjörn Larsson for spotting the typo.

Anthony

Mary Anning, actually, because without her, the others most likely would of went into other jobs. Mary Anning inspired them.

Pingback: Πωλήθηκε πανάκριβα γράμμα βικτωριανής γυναίκας που περιείχε κόπρανα! | SELENE

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #09 | Whewell's Ghost

Torbjörn Larsson

Three times “Wegner”. Surely it is spelled Wegener? [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Wegener ; http://www.zechlinerhuette.com/de/tourismusinfo/wegener_gedenkstaette.php ; /pedantic with names]

Tom Dill

I vote for Mary Anning. All the candidates had a big influence on geology, and deserve recognition. But Mary Anning dates from the earliest years of paleontology, befitting the title “mother of geology”. By finding new species and providing countless specimens, she had a huge impact on this then-new science, even while she was kept outside the scientific societies and academe.

Robbie Gries

Florence Bascom was not just a first within the science…she educated and sent into the world an army of smart and capable female geologists who continued to flourish and multiply and excite generations of women for our science. She is not one woman, she is a hundred women. Well, maybe a thousand by now.

surajit kar.

Marie Tharp , because not only her general contribution in the field of geology but she also produced the Oceania map & identified the existence of mid Atlantic ridge.

Ronney Tapwa

I think the tittle should go to Florence Bascom,because she is first woman to contribute her knowledge in geology.