What are the most interesting, cutting-edge and compelling research topics within the scientific areas represented in the EGU divisions? Ground-breaking and innovative research features yearly at our annual General Assembly, but what are the overarching ideas and big research questions that still remain unanswered? We spoke to some of our division presidents and canvased their thoughts on what the current Earth, ocean and planetary hot topics will be.

Because there are too many to fit in a single post we’ve brought some of them together in a series of posts which will tackle three main areas. The first post focused on the Earth’s past and its origin, while the second post focused on the Earth as it is now and what its future looks like. Today’s is the final post of the series and will explore where our understanding of the Earth and its structure is still lacking. We’d love to know what the opinions of the readers of GeoLog are on this topic too, so we welcome and encourage lively discussion in the comment section!

A new, modern, era for research

That we have great understanding of the Earth, its structure and the processes which govern how the environment works, is a given. At the same time, so much is still unknown, unclear and uncertain, that there are plenty of research avenues which can help build upon, and further, our current understanding of the Earth system.

![By Camelia.boban (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.egu.eu/network/geosphere/files/2015/12/BigData_hot-topics-300x152.jpg)

Big Data’s definition illustrated with text. Credit: Camelia.boban (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The structure of the Earth

Despite a long history of study, including geological maps, studies of the structure of the Alps, and the advent of analogue models some 200 years ago, there is much left to learn about how geological processes interact and shape our Earth.

Some important unanswered questions in the realm of Tectonics and Structural Geology (TS) include:

“Why do some passive margins have high surface topography (take Norway, or Southeastern Brazil as an example) even millions of years after continental break-up? How does subduction, the process by which a tectonic plate slides under another, begin? And how does the community adapt to new research methods and ever growing datasets?” highlights Susanne Buiter, TS Division.

One important problem is that of inheritance and what role it plays in how plate tectonics work. Scientists have known, since the theory was first proposed in the 1950s (although it only became broadly accepted in the 1970s), that our planet is active: its outer shell is divided into tectonic plates which slide, collide, pull away and sink past one another. During their life-time the tectonic plates interact with surface process and eventually flow into the mantle below. This implies that any new tectonic processes will take place in material that carries a history.

“It is increasingly recognised that tectonic events do not act on homogenous, pristine materials, but more likely on crust that is cross-cut by old shear zones, incorporates different lithologies and which may have inherited heat from previous deformation events (such as folding),” explains Susanne.

So the key is: what is the impact of historical inheritance on tectonic events? Can old structures be reactivated and if so, when are they reactivated and when not? Do the tectonic processes control the resulting structures or is it the other way around?

Seismology too can shed more light on how we understand Earth processes and the structure of the planet.

“An emerging field of research is seismic super-resolution: a promising technique which allows imaging of the fine-scale subsurface Earth structure in more detail than has been possible ever before,” explains Paul Martin Mai, President of the Seismology (SM) Division.

The methodology has applications not only for our understanding of the structure and process which take place on Earth, but also for the characterisation of fuel reservoirs and identification of potential underground storage facilities. That being said, the technique is still in its infancy and more research, particularly applied to ‘real’ geological settings is needed.

Understanding natural hazards

The reasons to pursue further understanding in this area are diverse and wide-ranging: amongst the most relevant to society is being able to better comprehend and predict the processes which lead to natural disasters.

Earthquake 1920 (?). Credit: Konstantinos Kourtidis (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

It goes without saying that, due to their destructive nature, earthquakes are a topic of continued cross-disciplinary scientific research. Generating more detailed images of the Earth’s structure, using seismic super-resolution for instance, can also improve our understanding of how and why earthquakes occur, as well as helping to determine large-scale fault behaviour.

And what if we could crowd source data to help us understand earthquakes better too? LastQuake is an online tool, operated via Twitter and an app for smartphones which allows users to record real-time data regarding earthquakes. The results are uploaded to the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) website where they offer up-to-data information about ongoing shake events. It was used by over 8000 people during the April 2015 Nepal earthquakes to collect eyewitness observation, including geo-located pictures, testimonies and comments, in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake.

In this setting, citizens become scientists too. They contribute data, by acquiring it themselves, which can be used to answer research questions. In the case of LastQuake, the use of the data is immediate and can contribute towards easing rescue operations and alerting citizens of dangerous areas (for instance where buildings are at risk of collapse) providing a two-way communication tool.

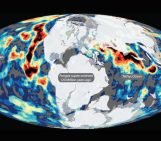

Global temperatures and climate change

It is not only earthquakes that threaten communities. Just as destructive can be extreme weather events, such as typhoons, cyclones, hurricanes, storm surges, severe rainfalls leading to flooding or droughts. With the increased frequency and destructiveness of these events being linked to climate change understanding global temperature fluctuations becomes more important than ever.

Flooded Mekong. Credit: Anna Lourantou (distributed via imaggeo.egu.eu)

Over periods of months, years and decades global temperatures fluctuate.

“Up to decades, the natural tendency to return to a basic state is an expression of the atmosphere’s memory that is so strong that we are still feeling the effects of century-old fluctuations,” says Shaun Lovejoy, President of the Nonlinear Processes Division (NP).

Harnessing the record of past-temperature fluctuations, as recorded by the atmosphere, can provide a more accurate way to produce seasonal forecasts and long-term climate predictions than traditional climate models and should be explored further.

Geoscience hot topics

Be it studying the Earth’s history, how to sustainably develop our communities, or simply understanding the basic principles which govern how our planet – and others – operates, the scope for avenues of research in the geosciences is vast. Moreover, the advent of new technologies, data acquisition and processing techniques allow geoscientists to explore more complex problems in greater detail than was ever possible before. It’s an exciting time for geoscientific research.

By Laura Roberts Artal in collaboration with EGU Division Presidents