A six month long eruption accompanied by caldera subsidence and huge amounts of emitted gasses and extruded lavas; there is no doubt that the eruption of the Icelandic volcano in late 2014 and early 2015 was truly remarkable. In a press conference, (you can live stream it here), which took place during the recent EGU General Assembly, scientists reported on the latest from the volcano.

Seismic activity in this region of Iceland had been ongoing since 2007, but in late August 2014 a swarm of earthquakes indicated that the activity at Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun was ramping up a notch. By August 18th, over 2600 earthquakes had been registered by the seismometer network, ranging in magnitude between M1.5 and M4.5. Scientist now know that one of the main drivers of the activity was the collapse of the ice-filled Bárðarbunga caldera.

Caldera collapses -where the roof of a magma chamber collapses as a result of the chamber emptying during a volcanic eruption – are rare; there have only been seven recorded events this century. The Bárðarbunga eruption is the first caldera collapse to have occurred in Iceland since 1875. They can be very serious events which result in catastrophic eruptions (e.g. the Toba eruption of 74,000 BP). In other cases the formation of the large cauldron happens over time, with the surface of the volcano slowly subsiding as vast amounts of magma are drained away via surface lava flows and the formation of dykes. Bárðarbunga caldera subsided slowly and progressively, much more so than is common for this type of eruption, to form a depression approximately 8km wide and 60m deep.

“The associated volcanic eruption, which took place 40km away from the caldera, was the largest, by volume and mass of erupted materials, recorded in Iceland in the past 230 years”, described Magnus T. Gudmundsson, Professor at the Institute of Earth Sciences at the University of Iceland, during the press conference.

If the facts and figures above aren’t sufficiently impressive, the eruption at Holuhraun also produced the largest amount of lava on the island since 1783, with a total volume of over 1.6 km3 and stretching over more than 85 km4. In places, the lava flows where 30 m thick!

The impressive figures shouldn’t detract from the significance of the events that took place during those six months: scientists were able to observe the processes by which new land is made on Earth! Major rifting episodes like this “only happen once every 50 years or so”, explained Gudmundsson.

So what exactly have scientists learnt? Most divergent boundaries – where two plates pull apart from one another – are found at Mid-Ocean Ridges, meaning there is little opportunity to study rifting episodes at the Earth’s surface. The eruption at Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun offered researchers the unique opportunity to take a closer look at how rifting takes place; something which so far has only been possible at the Afar rift in Ethiopia.

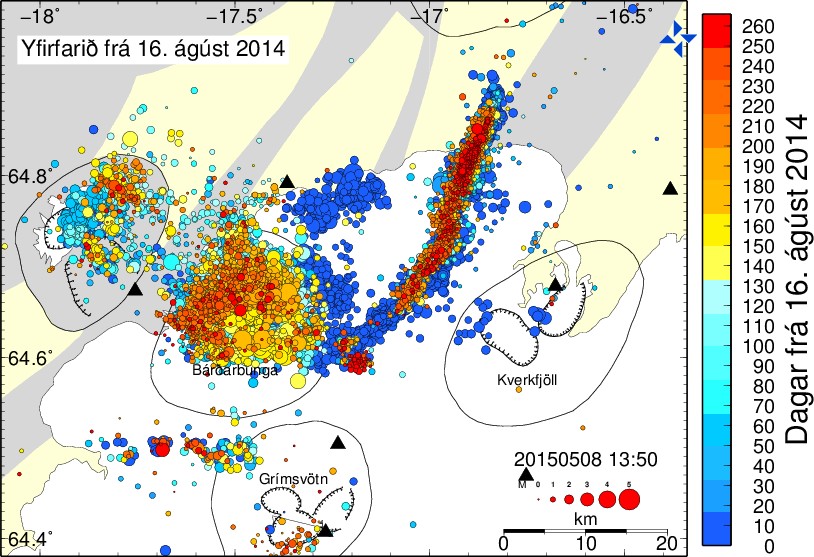

New crust is generated at divergent plate margins, commonly fed by vertical sheet dykes – narrow, uniformly thick sheets of igneous material originating from underlying magma chambers. Dykes at divergent plate boundaries are common because the crust is being stretched and weakened. One of the clusters of seismic activity at Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun was consistent with the formation of a dyke. The seismic signal showed that the magma from the Bárðarbunga caldera, rather than being transported vertically upwards to the surface, was in fact being transported laterally, forming a magma filled fissure which stretched 45 km away from Bárðarbunga. This video, from the Icelandic Met Office, helps to visualise the growth of the dyke over time.

The figure shows all the earthquakes which took place in the region in and around Bárðarbunga, from 16 August 2016 until 3 May 2015. The bar on the right counts days since the onset of events, and it gives a colour code indicative of the time passed. The dark blue colour implies the oldest earthquakes whereas the red colour implies the youngest earthquakes. The earthquakes clearly show the growth of a lateral dyke, headed northeast, away from the Bárðarbunga caldera. Click here to enlarge the map. (Credit: Icelandic Meteorological Office)

Further study of the dyke using understanding gained the from propagating seismicity, ground deformation mapped by Global Positioning System (GPS), and interferometric analysis of satellite radar images (InSAR), allowed scientists to observe how the ground around the dyke changed in height and shape. The measurements showed the dyke was not a continuous feature, but rather it appeared broken into segments which had variable orientations. Modelling of the dyke revealed that it was the interaction of the laterally moving magma with the local topography, as well as stresses in the ground cause by the divergent plates, that lead to the unusual shape of the dyke.

On average, magma flowed in the dyke at a rate of 260 m3/s, but the speed of its propagation was extremely variable. When the magma reached natural barriers, it would slow down, only picking up momentum again once pressure built up sufficiently to overcome the barriers. Shallow depressions observed in the ice of Vatnajokull glacier (the white area in the map above) – known as Ice cauldrons – were caused by minor eruptions underneath the ice at the tips of some of the dyke segments. The dyke propagation slowed down once the fissure eruption at Holuhraun started in September 2014.

What has the Bárðarbunga-Holuhraun taught scientists about rifting processes? It seems that at divergent plate boundaries, in order to create new crust over long distances, magma generated at central volcanoes (in this case Bárðarbunga), is distributed via segmented lateral dykes, as opposed to being erupted directly above the magma chamber.

By Laura Roberts Artal, EGU Communications Officer

Further reading and references

You can stream the full press conference here: http://client.cntv.at/egu2015/PC7

Details of the speakers at the press conference are available at: http://media.egu.eu/press-conferences-2015/#volcano

The speakers at the press conference also reported on the gas emissions as a result of the Holuhraun fissure eruption and the implications for human health. You can read more on this here: Bardarbunga eruption gases estimated.

Sigmundsson, F., A. Hooper, Hreinsdóttir, et al.: Segmented lateral dyke growth in a rifting event at Bárðarbunga volcanic system, Iceland, Nature, 517, 191-195, doi:10.1038/nature1411, 2015.

Sigmundsson, F., A. Hooper, Hreinsdóttir, et al.: Segmented lateral dyke growth in a rifting event at Bárðarbunga volcanic system, Iceland, Geophys. Res. Abstr.,17, EGU2015-10322-1, 2015 (conference abstract).

Hannah I. Reynolds, H. T., M. T. Gudmundsson, and T. Högnadóttir: Subglacial melting associated with activity at Bárdarbunga volcano, Iceland, explored using numerical reservoir simulation, Geophys. Res. Abstr.,17, EGU2015-10753-2, 2015 (conference abstract).

Pingback: What’s Up With the Quakes Before a Volcano Erupts? | News

Pingback: What’s Up With the Quakes Before a Volcano Erupts? | Breaking News Pakistan

Pingback: What’s Up With the Quakes Before a Volcano Erupts? | TechLives

Pingback: What’s Up With the Quakes Before a Volcano Erupts? | SciMerge

anthony

You state that “the lava flows where 30 km thick!” surely that is incorrect and you meant 30 m ?

Laura Roberts-Artal

Thank you for pointing this out. It is indeed a typo which is now fixed.

Pingback: Hvernig Bárðarbunga seig saman | Jarðfræði á Íslandi

Pingback: How Bárðarbunga volcano collapsed | Iceland geology