The EGU’s #vEGU21 streamed a wide variety of virtual sessions from Short Courses to Union Symposia. While most #vEGU21 sessions had a specific scientific focus, a few highlighted topics that were of interest to geoscientists across multiple disciplines. The Union Symposia 3: “A Climate and Ecological Emergency: Can a pandemic help save us…?” was one of these sessions with a high level of participant engagement from experts across the geoscience spectrum. Moderated by Rolf Hut, Researcher at the Delft University of Technology, the session identified key lessons that the scientific community can learn from the pandemic and how they can be applied to the climate emergency.

The lessons discussed during this session were extremely complex and multifaceted, and consequently needed a diverse panel of speakers to address them! This blog post will highlight the key points that were outlined by the session’s diverse panel members, including:

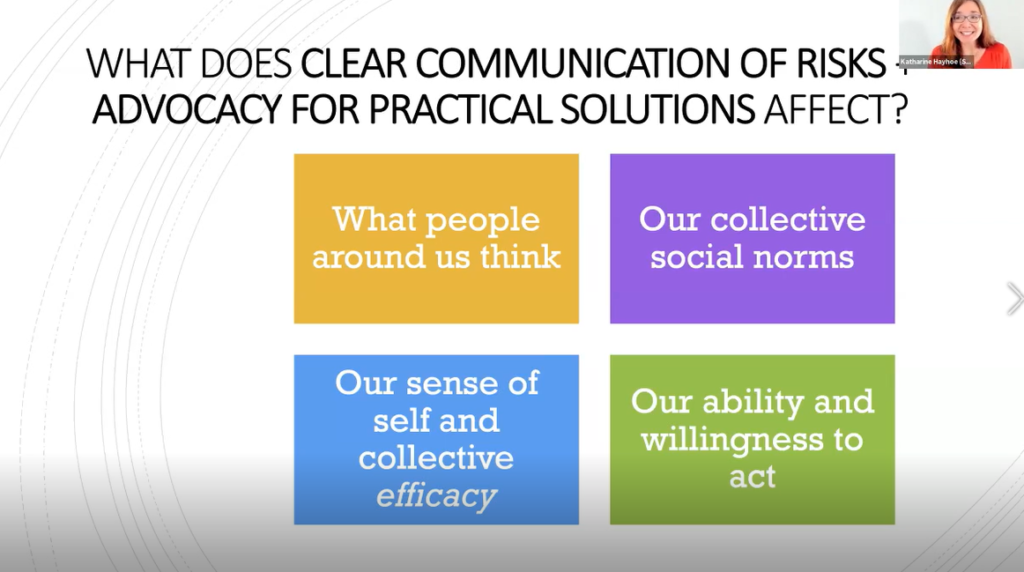

- Katharine Hayhoe: Professor of political science at Texas Tech University, Director of the Climate Science Center. CEO of the consulting firm ATMOS Research and Consulting.

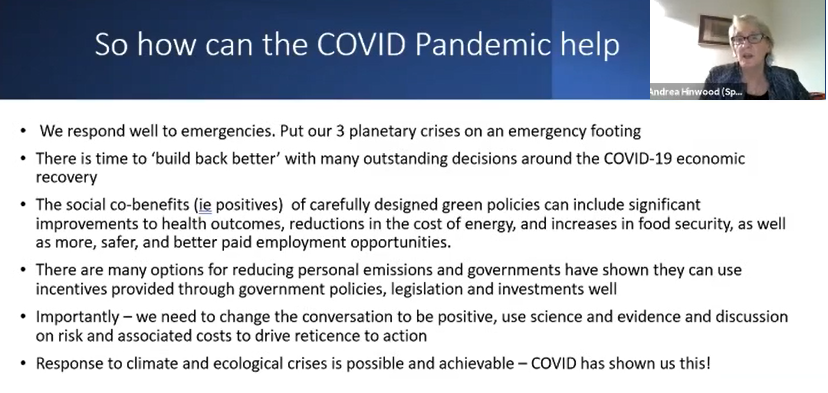

- Andrea Hinwood: Chief Scientist, UN Environment Programme.

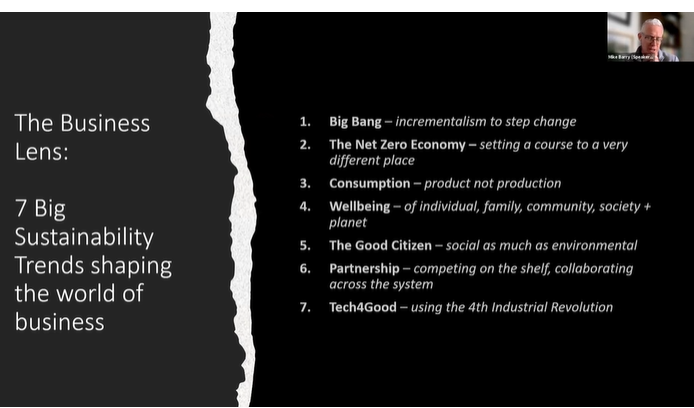

- Mike Barry: Director of Mikebarryeco, Strategic Advisor for Instinctif Partners and Clim8 Invest, and Board Trustee of A Blueprint for Better Business.

- David Mair: Head of Unit, Knowledge for Policy: Concepts and Methods, European Commission Joint Research Center.

COVID-19 and the Climate Emergency: finding common ground

Although similarities between COVID-19 and the climate emergency might not seem immediately obvious, Katharine Hayhoe kicked-off the discussion by outlining a number of similarities. Both COVID-19 and climate change are public health concerns that disproportionately impact those who are vulnerable. The scientific community has known about the risks of each before they became immediate issues to society and both have become politicised.

COVID-19: learning from an effective global response

During her presentation, Andrea Hinwood outlined some observations about the positive aspects of the COVID-19 response in many countries, highlighting that the “swift response to control the spread and to mitigate social and economic impacts” was possible because it was perceived as a global emergency. COVID-19 demonstrated we “can take local, national, and coordinated international action relatively quickly.” Hinwood continued, “We’ve also contributed enormous funds, demonstrated a willingness to protect public health […], shared information, […] and made lifestyle changes really quickly”. Once the climate crisis is perceived as an emergency, we might be able to elicit a similar response.

Mike Barry, presenting the issue from a business perspective, agreed that it’s no longer about “becoming 2% less bad every year in the way that could reduce carbon emissions in the past. [It] is about fundamentally changing every aspect of business”. He emphasised that the pandemic was the “last nail in the coffin of globalization 1.0; we need a new system”. Barry went on to outline the seven big trends that he sees businesses now using to accelerate action against climate change, including greater partnerships between competitors, the role of the good citizen, and the concept of wellbeing driving change.

Understanding your audience and framing your research

During her presentation, Hayhoe indicated that while scientists understand the need for climate action very well, they aren’t successfully communicating it to the public. “I think that we have been guilty of assuming that the reasons why we scientists are alarmed are sufficient to convince everyone else of the need for action.” She continued,

we can no longer assume that just overwhelming people with an avalanche of scientific information will result in constructive policies.

Hayhoe emphasised the importance of linking the impacts of climate change with things that people can connect with and care about because “we don’t talk about something if we don’t think it matters to us.” Making this connection isn’t as difficult as you might think because, as Hayhoe outlined, climate change is something that is already impacting almost every area of our lives. “Climate change is an everything issue. It affects the air we breathe, it affects the water we drink, the food we eat, it affects the economy, business, jobs, national security; it affects everything we care about. It’s about real people and real places and real issues that matter to every one of us today.”

Hinwood expanded on Hayhoe’s statement by highlighting the importance of having a two-way conversation,

We also need to listen. Sometimes we’re so intent on trying to convey a particular viewpoint [that we forget to].

David Mair outlined the importance of not only understanding the audience’s motivation but also their values. All people, regardless of their profession or IQ, are biased toward their own prior opinions and attitudes. Mair explained that these opinions and attitudes influence how we react to certain information and that “We have enormous difficulty in accepting facts that challenge our core convictions.” While these underlying values don’t necessarily dictate a particular policy course or action, they may impact what people want and how they react to a particular issue.

Mair therefore advises scientists to “Do the hard yards” to understand these values and frame their research depending “on who you’re talking to… Or which values you’re talking to”. In doing so, Mair stated that scientists will have “given people good reason and cause and argument. You’ve listened to their argument, you’ve addressed their concerns.” He also underscored that speaking to an audience’s values doesn’t mean misleading them and that scientists should “frame the scientific evidence in ways which remains truthful and noncontradictory and accurate”.

Switching the conversation

Scientists know that climate change is scary and can be a depressing discussion topic but Hinwood outlined the need for scientists to switch the conversation. “The way we communicate is becoming more important.” She continued, “if we say we’ll have death and mayhem, people switch off”. There are often opportunities for scientists to instead focus on what they can do “to use science and evidence to discuss risk and associated costs to drive action.”

Mike Barry agreed on the need to find opportunities to drive change by offering people “Great solutions. Great cars, foods, holidays, that also fund more sustainability.” He continued,

We need to excite people! We can’t just tell them this is about the end of the world. We need to give them exciting options.

Mair emphasised that it’s not only what scientists say that is important, but also how they say it. He explained that the scientific community is very unique in that it prizes “truth-telling and fact and accuracy” above all. This can sometimes result in scientists coming across as blunt or arrogant when communicating with non-experts. “Scientists don’t take many prisoners when they debate, they really don’t. That’s great for the scientific process but I think the public can infer different things about their perhaps slightly intemperate nature.” Mair subsequently highlighted humility as a skill that scientists can learn to more effectively communicate their research with non-experts.

The role of scientists in responding to crises

To end the session, the panellists gave further detail on how the scientific community can contribute to climate solutions. Hinwood urged the audience to get more engaged in climate issues, “Work out how you can get involved and where you can make a difference.” She also gave advice to scientists wanting to engage with policymaking, “Always partner with someone who is going to use your work because they give you that perspective too.” She also encouraged scientists to get their “science communication skills honed” so that they are ready to move into a different career and “deal with people from a range of different disciplines.”

Hayhoe expanded on this by highlighting the broad range of scientific outreach activities that scientists can engage with. “There’s a whole spectrum over which scientists can contribute. And there’s no one right place for any one person to be on that spectrum. We need people doing the sound science, publishing it in peer-review journals. We need people writing essays. We need people to engage with local businesses and elected officials.” She specified that “Outreach can take up as much time as we allow it.” How we choose to use that time, is up to us!

Barry reminded the audience that it isn’t only policymakers and the public that need science, but also business leaders. He also urged scientists to see businesses as part of the solution. “We’ve got an opportunity for the next five or ten years to radically reimagine society and the economy that supports it. And those radical changes have to be informed by science. [Scientists need to] explain the need for change, the possibility of change, and actually how it can be fundamentally better for us all. I’m very excited about how we can do that!”

In closing, Mair re-emphasised the need for “science in massive quantities and at the very highest quality” while also making it clear that, although science should inform policymakers, it cannot make the decisions on their behalf. He also encouraged scientists to “read a little bit of the science of science for policy” and gain a better understanding of behavioural biases. He argued that this will improve their knowledge about how information can be effectively communicated to different groups depending on their values and motivations.

We hope that you found this session and blog post compelling! Thanks once again to all of the speakers and the conveners involved in this session – and thank you to the audience for asking such interesting questions! If you want to watch the whole discussion you can view it for free on YouTube!