I am a petrographer at the University of Padova, Italy, studying the metamorphic rocks that form the deep Earth’s crust beneath our feet, and what happens when they get so hot to start to melt.

I’ve spent (enjoyed I should say) more than 30 years looking at rocks with an optical microscope. This simple, cheap tool, and more importantly, its skilled use, remain key ingredients for good research in petrology!

I’ve been taught by scientists, like Ron Vernon of Macquarie University in Australia, that a good micrograph is essential to document my research and strengthen my conclusions, and so I’ve always paid particular attention to the quality of photos. In the meanwhile, I have also developed a particular interest in photomicroscopy with an aesthetic purpose, realizing that the cocktail of rocks and polarized light has an extraordinary potential in the ‘sciart’ (Science-and-Art) field.

The digital revolution has marked a turning point in this activity, and 10 years ago I have started my micROCKScopica project to showcase to the public the beauty hidden in the small slices of rock that are thin sections.

When I find a photogenic rock I play with polarizers to get the desired combinations of color, and then I take a photograph. And people can enjoy the images, their colors and shapes, even without knowing the geological history behind them.

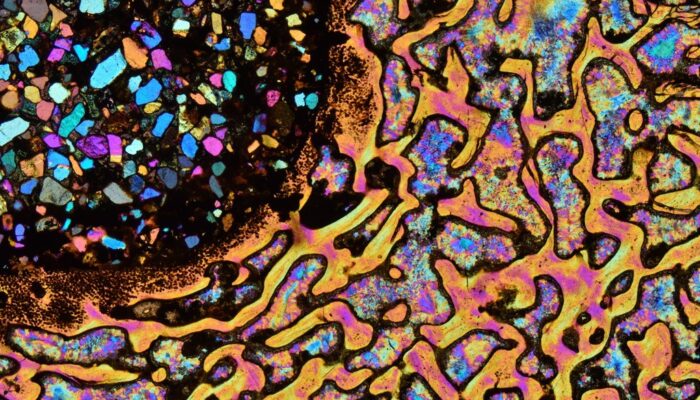

This is particularly true for this photograph: it is a thin section of a piece of dinosaur bone but I don’t know much about it (what bone, which dinosaur), only that it had been collected in Utah, in the United States. I received a small sample of the bone by Denise M. Harrison, a friend with whom I collaborated for a book on Lake Superior Agates. She is an award-winning lapidary (someone who cuts, polishes and engraves stones), and makes lovely cabochons with all sort of semiprecious, hard stones. I asked her for some leftovers to make some thin sections, because I wanted to see something new, possibly silicified (impregnated with silica during fossilization) because chalcedony – the very fine-grained variety of common quartz – may be extremely photogenic.

I had no idea of how a bone could look like under the microscope, and the first sight left me speechless! The porous structure, and the patterns of the radiating textures in the chalcedony fillings are extraordinary, and provide a wealth of possibilities for nice images.

In this shot, that I replicated in red and blue, a larger hole had been filled with a fine-grained quartz sand – the dark moon shape on top left – somehow interrupting the regular pattern of the bone tissue, that to someone may recall Australian Aboriginal artwork.

Curiously, this anatomically-related image made me quite popular among pathologists and other medical doctors, who find many analogies with their subjects of research. The ages of the specimens are some hundred million years apart, though…

By Bernardo Cesare, University of Padova, Italy

www.microckscopica.org

Editor’s note: The fossil sample featured in this photo was collected and distributed legally from Utah.

If you pre-register for the 2019 General Assembly (Vienna, 07–12 April), you can take part in our annual photo competition! From 15 January until 15 February, every participant pre-registered for the General Assembly can submit up three original photos and one moving image related to the Earth, planetary, and space sciences in competition for free registration to next year’s General Assembly! These can include fantastic field photos, a stunning shot of your favourite thin section, what you’ve captured out on holiday or under the electron microscope – if it’s geoscientific, it fits the bill. Find out more about how to take part at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/photo-contest/information/.

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.