Patagonia, the region in southernmost tip of South America, is as diverse as it is vast. Divided by the Andes, the arid steppes, grasslands and deserts of Argentina give way to the temperate rainforests, fjords and glaciers of Chile. Also on the Chilean side are rolling hills and valleys of marshy topography: Patagonia’s bogs. Today, Klaus-Holger Knorr, a researcher at the University of Münster’s Institute for Landscape Ecology, tells us about what makes these peatlands so unique.

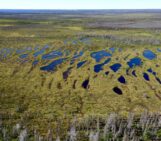

This picture shows an ombrotrophic, oceanic bog at the Seno Skyring Fjord, Patagonia, Chile. It is a view from the inner part of the peatland south toward the shore of the Fjord, in the background Isla Escapada and the Gran Campo ice field. Ombrotrophic bogs are peatlands (accumulations of more or less decomposed plant material which collect in a water-saturated environment) receiving their water and nutrients solely from the atmosphere, i.e. by rain, wet and dry deposition.

Similar to their Northern counterparts in Canada, Northern US, Fennoscandia or Siberia, these southern Patagonian peatlands formed after the last deglaciation and accumulated huge amounts of carbon as peat.

Peatlands cover only about 3 % of the global land surface but store about a third of the soil carbon pool. Peat is formed primarily as there is excess rainfall, peat soils are water logged, oxygen gets depleted, and decomposition is limited. Pristine, undisturbed peatlands can store as much as 10-50 g carbon per square meter and year.

What makes the peatlands in Patagonia particularly interesting is their pristine, undisturbed conditions and extremely low input of nutrients from the atmosphere, compared to the high input into sites in densely settled or industrial regions. This allows studies of peatland functioning under natural conditions and absence of anthropogenic impacts.

Moreover, peatlands in Patagonia harbor a specific kind of vegetation, including cushion forming plants such as Astelia pumila and Donatia fascicularis. These cushion forming plants have a very low above ground biomass but an extremely large rooting system, reaching down to a depth of >2 m in case of A. pumila. As these roots act as conduits for oxygen to sustain viability of the roots in the water logged peat, they have been shown to aerate large parts even of the saturated zone, thereby impeding high methane production and emission. Oxygen supply by these roots is even hypothesized to stimulate peat decomposition and thereby lead to particularly decomposed peat under cushion plant cover.

Another plant species only occurring in peatlands of Southern Patagonia, a small conifer named Lepidothamnus fonkii, has developed a particular strategy to overcome nutrient deficiency: it has formed a close association with bacteria being able fix atmospheric nitrogen to fulfill the demand of nitrogen for growth. While such nitrogen fixation is well known for legumes and some tree species, it has rarely been found for conifers.

A further important factor for peatlands in Patagonia, leading to the term “oceanic bogs”, is the fact that these peatlands in close vicinity to the seashore receive high inputs of sea salts from sea spray, modifying availability of associated elements such as Sodium, Calcium, Magnesium, Sulphur and others.

By Klaus-Holger Knorr, researcher at the University of Münster’s Institute for Landscape Ecology

Imaggeo is the EGU’s online open access geosciences image repository. All geoscientists (and others) can submit their photographs and videos to this repository and, since it is open access, these images can be used for free by scientists for their presentations or publications, by educators and the general public, and some images can even be used freely for commercial purposes. Photographers also retain full rights of use, as Imaggeo images are licensed and distributed by the EGU under a Creative Commons licence. Submit your photos at http://imaggeo.egu.eu/upload/.