In this month’s GeoEd column, Sam Illingworth tells us about the growing use of Citizen Science within research as a means of acquiring data. Whilst the practice is novel and offers exciting opportunities as to volumes of data collected Sam highlights the importance of appropriately crediting the work of the willing volunteers.

Citizen Science is a phrase that is currently de rigour in scientific communication circles. In essence it can be thought of as a form of collaborative research that involves members of the general public (or citizens), which actively involves them collecting or generating data.

There are many examples of citizen science projects in the geosciences, including Old Weather a ‘data mining’ citizen science project that aims to help scientists recover Arctic and worldwide weather observations made by US ships since the mid-19th century, by enlisting citizens to interpret old transcriptions (e.g. track ship movements) in order to generate new data. Such ultimately improves our knowledge of past environmental conditions, with a better understanding and capability to model these past occurrences ultimately leading to an improvement in modelling future events.

Just some of the cropland that still needs to be captured! (Photo Credit: Tony Atkin)

Another example of a citizen science project in the geosciences, and again one which involves data analysis rather than data creation, is Cropland Capture, which focused on improving current cropland extent by classifying all very high resolution images found on Google Earth to create a wall-to-wall map of cropland. Accurate and reliable global cropland extent maps are essential for estimating and forecasting crop yield, in particular losses due to drought and production anomalies. Realising the tremendous scale of this task, developers created a multi-platform game in which players were provided with a satellite image or in-situ photo, and had to determine if the image contained cropland or not. This element of ‘gamification’ is a popular way of engaging members of the general public, with prizes awarded to the top 3 capturers in an award ceremony in May of this year. The success of this approach is evident by the fact that over 4.5 mil sq km of land was validated during the 6 months of this project!

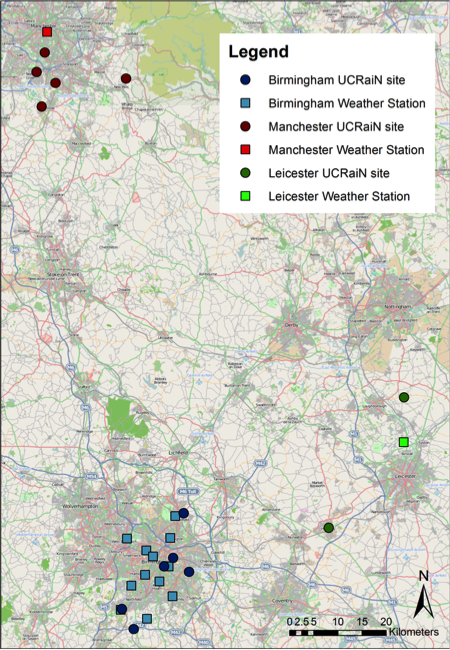

There are also a number of citizen science programmes that actively source data directly from members of the public. For example, the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) is a non-profit, community-based network of volunteers who measure and map precipitation using low-cost measurement tools with an interactive website. The project started in Colorado in 1998 and now has networks across the US and Canada, involving thousands of volunteers, making it the largest provider of daily precipitation observation in the US. CoCoRaHS inspired a similar project that was trialled in the UK, the ‘UK Community Rain Network’ (UCRaiN), which showed the potential for setting up a UK-based network. As well as improving the coverage of the current network of raingauges, and therefore the potential application to forecasting, nowcasting, satellite and radar validation, flood warning systems and decision making, a community rainfall collection scheme has the the additional benefit of encouraging citizens to become involved in meteorological science, thereby heightening their awareness about weather.

Map showing the locations of the participating UCRaiN sites (schools and individuals). The meteorological sites used for comparison are shown by the square symbols (Photo Credit: Illingworth, et al.)

The main objection to these types of citizen science projects are that they are potentially tantamount to free labour; with scientists using the general public to collect and/or analyse vast swaths of data, whilst they steal all of the ‘glory’, perhaps in a matter analogous to a particularly unsympathetic professor and their postgraduate students. After all, whilst there are many incentives for mining and analysing the data, it is not the citizens whose name will be appearing on the research papers and grant applications that so often come about from these projects. By appealing to the noble intentions of the citizens, and placing an emphasis on the progression of science for the greater good, is there not the risk that some of the researchers sitting atop of these projects come across as hypocritical?

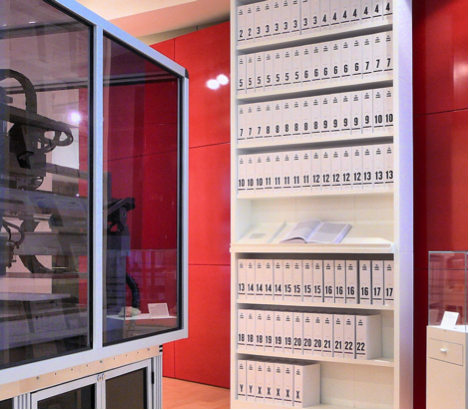

Perhaps the most famous example of a truly collaborative citizen science project is the Human Genome Project, an international scientific research project with the goal of mapping all of the genes of the human genome from both a physical and functional standpoint. It remains the world’s largest collaborative biological project, and serves as a great example of science genuinely being conducted for and on behalf of the greater good. Whilst publically acknowledged projects such as this are obviously an extreme example (the Human Genome Project was conducted using $3 billion of public funding), there is still plenty of opportunity for researchers to ensure that the citizens that they employ are properly recognised. For example, in the UCRaiN project, all of the participating schools were given credit in the acknowledgments section of the research article that was produces as a result of the study.

The first printout of the human genome to be presented as a series of books (Photo Credit: CC-BY-SA-3.0; Released under the GNU Free Documentation License)

Overall, citizen science projects are becoming an increasingly popular means to engage the public, whilst also benefiting scientific research, especially given the growing ubiquity of social media and other communications platforms. However, there is a need to actively involve the participants in these projects, and to ensure that they receive the appropriate acknowledgments, otherwise we, as scientists, run the risk of treating our new colleagues as nothing more than second-class citizens.

By Sam Illingworth, Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University

Pingback: GeoLog | Mars Rocks – introducing a citizen science project

Pingback: GeoLog | A brief history of science communication