These blogposts present interviews with outstanding scientists that bloomed and shape the theory that revolutionised Earth Sciences — Plate Tectonics. Get to know them, learn from their experience, discover the pieces of advice they share and find out where the newest challenges lie!

Meeting Jean-Philippe Avouac

Prof. Jean-Philippe Avouac initially studied mathematics and physics during his undergraduate and graduate degrees. Later he got more inclined towards geophysics and then he discovered Earth Sciences. During his Ph.D. at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, advised by Paul Tapponnier, he immersed himself in geology and tectonic geomorphology. Currently, Jean-Philippe Avouac is a Professor of Geology at the California Institute of Technology.

Like living organisms, earthquakes have a life cycle: they nucleate, grow and arrest. There can be some lineage but each earthquake is a different being.

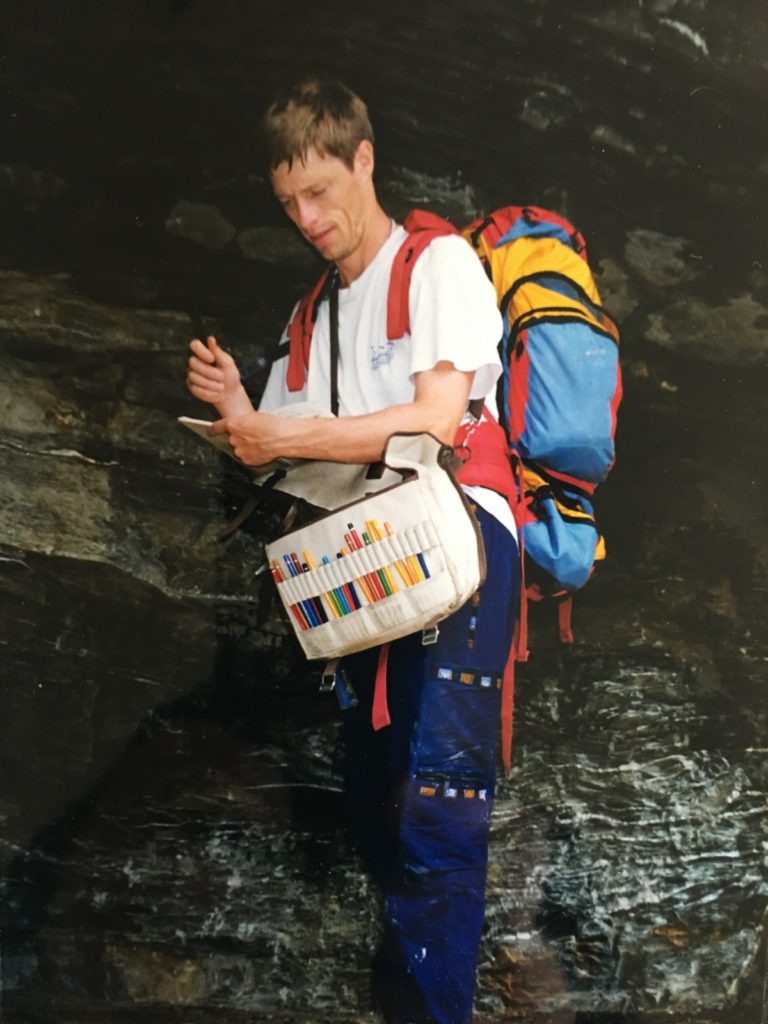

Fieldwork along the Kali Gandaki (Nepal) in 1999. Credit: Barbara Avouac

Where lies your main research interest?

I study crustal dynamics: How the crust is deforming as a result of earthquakes, but also as a result of viscous processes. I study the process of stress accumulation on faults, the release of this stress by earthquakes, as well as how earthquakes and other mechanisms of deformation are contributing to building the topography and geological structures in the long run.

How would you describe your approach and methodology?

In my group, we develop techniques to measure crustal deformation using in particular remote sensing and seismology. We were using radar images initially, and we have moved toward using more optical images with time and also GPS data… We try to reproduce the observations (geodetic deformation, kinematic models of seismic ruptures, gravity field…) using dynamic models to determine what are the forces and rheologies needed.

What would you say is the favorite aspect of your research?

What I like most about my research is mentoring Ph.D. students and postdocs. I love matching their skills with good problems, problems that will be attractive to them and that will resonate with the currently hot questions in Earth Sciences. I really love doing that.

The other thing I love is to use what I learned as I student (maths and physics) to answer science questions arising from natural observations. I love that part when you look at nature, you observe something and try to measure it quantitatively and then you try to explain the observation with dynamic models. I really enjoy going back and forth between observations and modelling. And the field! I really like being in the field… This is an aspect of the job that really attracted me initially.

We built from what other researchers had done before, but we reached quite different conclusions […] that’s exciting!

Jean-Phillipe Avouac leading a field excursion in the Dzungar basin, 2006. Credit: Aurelia Hubert-Ferrari

Why is your research relevant? What are the possible real-world applications?

A significant fraction of my research is relevant to seismic hazards. After my Ph.D., I worked for the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique (CEA) for 10 years. I was conducting seismic hazard assessment studies for nuclear facilities. So, I have been exposed to the applied side of earthquake science and I like that some of the research we do in my group can help to improve the way we do seismic hazard assessments.

But what I really want to say is that I do not think relevance should drive academic research. In that regard, I should say that I don’t like much the way the funding system works today. I think there is too much emphasis on relevance to society. The idea that you start from stating problems of societal relevance, and only then see what kind of research we can do to solve this problem is not a good approach, in my opinion. I don’t think this is the way important scientific discoveries are made. You make discoveries by being curious, by observing nature with an open mind, by exploring new ideas and coming up with new concepts, or by observing something that is not explained in the current theoretical framework that we have and then you make use of the knowledge that you build after looking at these problems. There is no way you can clearly anticipate where the joyful exploration of an intriguing idea or observation can lead but we know from experience that the society benefits from curious scientific exploration. So, although I think there is relevance in what I am doing, I do not think that, in general, relevance to society should be driving academic research.

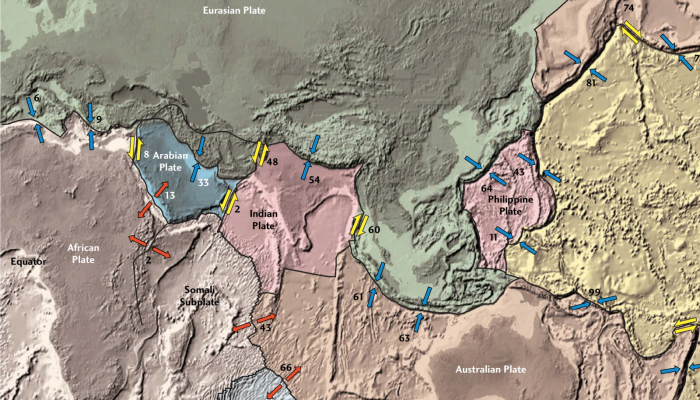

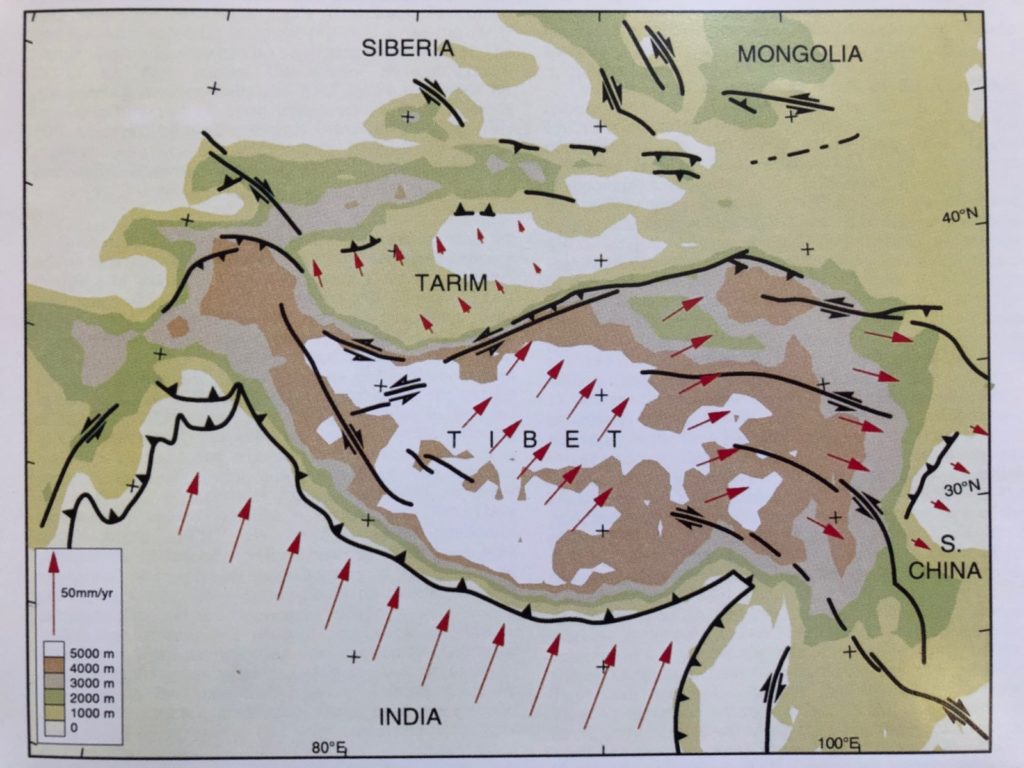

An outcome of Jean-Phillipe Ph.D Thesis, later published in Kinematic model of active deformation in Central Asia (Avouac and Tapponnier, GRL – 1993; doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/93GL00128).

I do not think relevance to society should drive academic research

What would you say is the main problem that you solved during your most recent project?

People in my group work on many different projects that are all very exciting to me. I’m going to mention just one project though because I can not possibly list them all.

We have done a lot of work in the past to develop techniques to invert geodetic measurements for fault slip at depth. A postdoc and a graduate students in my group have moved on to improve the technique and use it to document slow slip events in Cascadia over the last 15 years. That was a daunting work but their hard work and perseverance have really paid back. The end result is amazing! We see how the slow slip event initiate, propagate, arrest, trigger one another… We built from what other researchers had done before us, but we reached quite different conclusions given that we now have a more complete view of the behaviour of the system –that’s exciting! I anticipate that we are going to learn a lot about the dynamics of slow-slip events, and maybe it will have important implications for regular earthquakes!

What do you consider to be your biggest academic achievement?

The research for which my group is probably best known is that we have done in the Himalaya. In particular, we have built a model of the seismic cycle that explains the observations that we have from seismology, geodesy, geomorphology and geology. We worked a lot on the Himalaya, in part because I love mountains, but also because it is a very unique setting to study orogenic processes which are still active today. There is really no better place where you can get geological constraints on the thermal and structural evolution of the range. There is a lot of erosion and it has been going on for a long time, so the rocks that have been brought to the surface have recorded the thermal and deformation history over tens of million years. Our research has helped understand how the Himalaya has formed as a result of seismic and aseismic deformation, and I think it has yielded important insight on orogenic processes and the seismic cycle in general.

By the way, I don’t mean that earthquakes are periodic. Like living organisms, earthquakes have a life cycle: they nucleate, grow and arrest. There can be some lineage but each earthquake is a different being.

Animation showing the process of stress build up and release associated to earthquakes along the Main Himalayan Thrust fault, along which India is thrust beneath the Himalaya and Tibet. Credit: Jean-Philippe Avouac, Tim Pyle and Kristel Chanard.

We tend to build walls between disciplines […] We would not have been able to discover plate tectonics without a deep cross-disciplinary dialogue

What do you think are the biggest challenges right now in your field?

As I mentioned before, the funding system is an issue. Funding agencies are clearly making a big mistake in prioritizing social relevance as a criterion to evaluate proposals. Aside from that, the challenge that we have in the Earth Sciences is that we tend to build walls between disciplines. Specialization is a natural drift, and you can make a very successful career in a particular field pushing further a particular analytical or modelling technique. Also, it is easier to get funding for what you are known to be good at. As a result, walls between disciplines are building with time. The vocabulary is evolving in each individual discipline and it is increasingly difficult to make major advancements that can bridge different disciplines. In my research, I try to navigate from one discipline to the other… but it is a challenge –while it can be key to make significant discoveries, it takes time and effort. There are fewer and fewer people making a carrier this way. It can be dangerous because of a dilution effect, but at some point, it is needed. Look at plate tectonics for example: it happened because of advances in different disciplines but most importantly because some scientists were aware of these advances and were able to connect them and derive a coherent global framework. We would not have been able to discover plate tectonics without a deep cross-disciplinary dialogue.

Another challenge is that nowadays we have a lot more data than we used to have. This is both an opportunity and a threat. There is a trend to produce more and more publications, that look very solid because they use a lot of data, but that are in fact very incremental. More of the same is not necessarily advancing knowledge at a fundamental level. We have to be imaginative with regard to how to process the increasing flux of data, but it should not come at the cost of being imaginative with regard to what they mean.

I do not like the way the funding system works today

When you were in the early stages of our career, what were your expectations? Did you always see yourself staying in academia?

After my Ph.D. I did not stay in academia. But even when outside academia, I kept doing research, because I had an appetite for it and was working in an environment where scientific curiosity was valued, even if science was not the main objective. Although I was not unhappy at all outside academia, I decided to go back to it since I found it more exciting for myself: I like to solve scientific questions but there is not so much I could solve without the help of students and postdocs. I didn’t consider staying in academia after my PhD because there were sides of the academic life I did not feel comfortable with… I was finding people in academia to be a bit… difficult sometimes, with big egos and not so open minded. Also, we are a very conservative community. There’s a reason for that, for we as scientists have to be sceptical and to push back new ideas and new observations. I guess I have now become now one of those crazy and conservative academic guys (laughs)!

Mapping and sampling Holocene terraces abandoned by rapid climate-driven incision in the Tianshan. Credit: Luca Malatesta

If you have a new idea… you will probably have a hard time

What advice would you like to share with Early Career Students?

My first advice is to be aware of the important questions that we should try to solve. Not because they are relevant but because they are interesting and because they are timely, given the tools and data that we have access to. Being aware of the really big questions is important because we tend to forget them sometimes as we become more specialized. And be also aware of the new techniques available, especially those that you could draw from other fields; computer science or medical imagery for example… It is important to be curious and see what is happening in other fields so that you can transfer new ideas and new techniques to your own field and give a try at answering big science questions.

Be curious, be adventurous. Take risks. Try things that might not work. You might be losing your time but it is also an opportunity to make real fundamental advancements. You can make a career by increments, but I think it is not as rewarding as taking risks and really solving a difficult problem.

Follow your own dreams and don’t be intimidated by peer pressure. If you put a new idea on the table, a really new one, first, you will probably have a hard time expressing it clearly… And second, peers will most probably push back, as they should. So do not be intimidated, believe in your ideas, and keep adjusting and pushing them forward. I see too many times students or postdocs who meltdown and get discouraged if they receive a negative comment after a presentation… – I would say, that could, in fact, be a good sign! You may be doing something different and maybe people are not understanding because there is something disturbing and really new!

Jean-Phillipe Avouac. Credit: Trish Reda.

Interview conducted by David Fernández-Blanco