This Mind Your Head blog post is a follow-up from one of the talks during the online short course on mental health that aired during the last EGU General Assembly. Imposter syndrome is about the feeling of being afraid to be found to be an imposter. Note that I do not claim to be an expert; in the following, I simply list a few tricks that help me, and people I have talked to, to find their way in stressful times, and perhaps, hopefully, they help you too.

What is it?

Imposter syndrome as a term was first coined in a scientific article by Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978. It can take various forms, where it can be about the feeling of ‘not being good enough’, or ‘not smart enough’, ‘not efficient enough’, or that ‘everyone around you is doing better than you’. Many people experience thoughts along these lines, and that ‘it is only a matter of time before being unmasked as an imposter’ – hence the name “impostor syndrome”. Even though this first study by Clance and Imes indicated that more women suffer from imposter syndrome than men, later research has shown that it occurs in both men and women alike. Gender does seem to control the driving force: women more frequently have some performance anxiety, whereas men are more driven by the fear of not being successful enough. In my own experience, in academia the impression of not being good enough seems to be fairly omnipresent in men and women alike – though perhaps women are more comfortable sharing their stories. The cause of imposter-like thoughts in academia may lie in being constantly surrounded by smart people, and the longer you stay in the academic environment (from BSc, to MSc, to PhD, etc), the smarter and more talented your peers become. Then there is also the glorification of long working hours – often originating in the passion of most people, but there can be a fine line between passion and obligation. Moreover, the academic career pyramid, with less and less jobs one step up the career ladder, means there is a lot of competition. Such a competitive environment creates an ideal breeding ground for thoughts of being insufficient, and encourages working harder and longer hours.

Credit: Adapted from astrobites.org.

In which situations?

Credit: Pixabay. Distributed via Pexels.

Note that anxieties like imposter syndrome are not a constant companion through time (fortunately!). This trait is shared by many mental health-related issues: their intensity waxes and wanes depending on the other events in your life. The more stressful life becomes, the easier it becomes to pinpoint what other people do better than you, and to lose eye for your own strengths. Stressful moments where you feel the pressure to perform, such as a job interview, the first time on a new job or during networking events, are natural triggers for the doubt to set in. Note that how long it takes to settle in a new job isn’t fixed: in some jobs it takes days before you’re comfortable, but in other environments or during more stressful times in your life, it can take weeks or months. Somewhat counterintuitively, achieving a milestone can be a trigger for imposter-type of feelings as well. Milestones, such as publishing a paper, obtaining a grant or landing a shiny new job, can actually acutely bring in those negative and “mean” thoughts like the idea that “they” gave it to the wrong person.

Fight-or-flight?

The stress that comes with imposter-type thoughts triggers our natural instincts of fight-or-flight. This doesn’t literally mean attacking your (new) colleagues, but it can result in working even harder, during longer hours, just to prove you are worth it. It seems so easy to forget that if you weren’t worth it, you wouldn’t have been in the position in the first place… The risk of always working more, harder and longer is that you deplete your own energy supply. This could potentially lead to more severe consequences, such as burnout or depression. The other option, the flight response, can appear in the form of trivializing your own success. “Ah, that prestigious grant? Luck, not skill….” Meaning that you actually do not get the credit you deserve, and you decrease the chances of moving up on the career ladder. It can also result in finding excuses, so you don’t even have to start, thereby completely avoiding the chance of failure. Perhaps you’ll find a way to always be busy with less important, but more urgent issues. Maybe you party hard the night before a big presentation: if the presentation then doesn’t go well, you have the excuse of a hangover. This neatly avoids any chance of it being related to your own skills… All in all, this type of behaviour lessens the chances reaching your full potential, and that would be a waste for you and the world!

Possible solutions

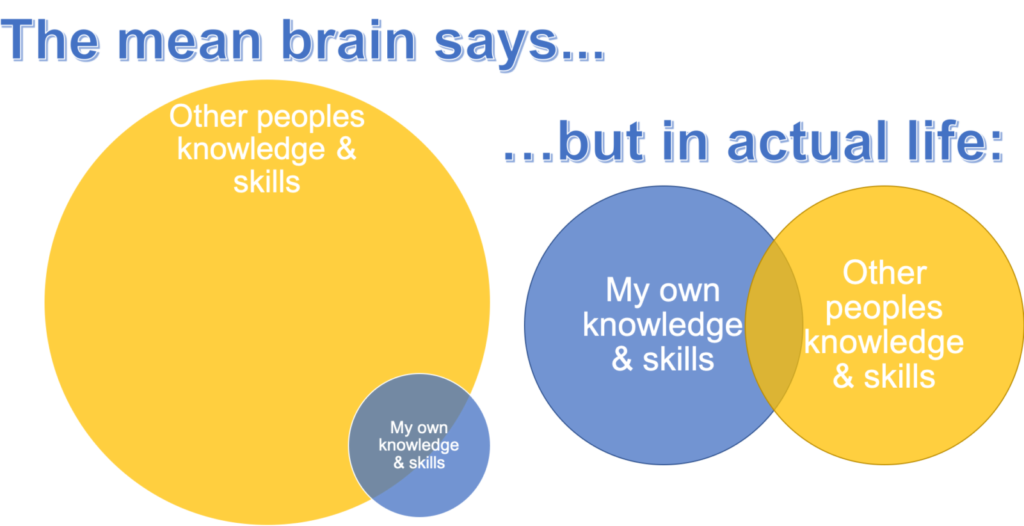

So, how to negate the devil voice in your head, this mean brain? Here, I would like to share some tricks concerning internal self-management, from self-observation, discussions with others, and from reading other blogs and such.

First of all, when you know your internal asshole, as I like to call it, it becomes easier to ignore. This can be as simple as knowing that voice in your head and that it always says the same. It can also be a more time-intensive, energy-consuming journey to your past, to figure out where your mean brain comes from: your parents, a nasty school teacher, jury of a competition you lost? I received once the hilarious advice to actually name that evil voice in your brain, though I haven’t made up my mind yet what would be a sufficiently evil name “The-voice-that-is-not-to-be-named” perhaps?

Second, you are not alone. Many, including numerous famous people (such as Sheryl Sandberg, David Bowie, Lady Gaga and Tom Hanks), have impostor syndrome. Talk to friends and colleagues you trust about the mean bits of your brain, and find out that you are your own worst judge. In a healthy working environment, others usually do not judge you as harshly as you judge yourself – it is too easy to focus on the one little detail that you did not do perfectly, instead of on the things you did really well!

Third, realize that your thoughts are not necessarily true. They are thoughts, not set in stone. I feel a certain way, because I think something. What am I thinking? Is this true? Are you trying to see in the future, thinking you know what other people are thinking about you, or are you simply focusing on one negative word in a sea of praise? You have a choice in what to do with your thoughts: do you believe them? I feel that especially scientists, with their inquisitive nature and fact-finding skills are well suited to judge their own thoughts.

Fourth, instead of looking around you what all the other people can do, think about what you can do: what is your unique skillset? You are a unique, wonderful person! We are all good at some things, and not so good at others. Even surrounded by amazingly skilled people, we all have a skill set that sets us apart. Take an objective look at yourself, and identify what makes you, you! This could be the “standard” scientific skill set of being a whizz in programming, a creative experimentalist, superquick in data-analysis or a brilliant and fast writer of articles and thesis chapters. But don’t forget the soft skills, which are equally important! Maybe you make amazing posters, are great at giving talks to a non-scientific audience, prepare the funniest lectures, or you are really good in planning and bringing the right people together.

And last, sometimes it is also OK to be passive, and not to fight your mean brain. Sometimes you are tired, and life just sucks today. It can simply be a rainy and gloomy day and nothing what you do or what people say cheers you up. But, don’t forget: all emotional states are temporary. So even if it sucks now, it will – most likely – be different tomorrow, or the day after, or next week. An awesome proverb I learnt off from the feel-good movie “the Marigold hotel”: all will be well in the end. If it is not well, it is not the end. Life continues!

Credit: Sydney Rea. Distributed via Unsplash.

Disclaimer: It is important to state here, that internal self-management, i.e. following tips and tricks as listed above, can help a lot. However, there where internal self-management is insufficient and a depression lurks around the corner, you need to be brave and find professional help near you. Remember: asking for help is one of the signs of strength, not of weakness!

Acknowledgment: this blog is inspired by an organizational workshop that I participated in, where the question was posed: which beliefs are present in the organization that stand in the way of change? Soon after that followed a workshop focusing on women in academia, with an invited speaker specifically targeting the impostor syndrome. These events and many discussions form the basis for this blog.