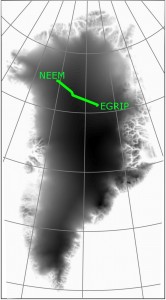

Moving 150 tonnes of equipment more than 450km across the Greenland Ice Sheet sounds like a crazy idea. In that context, moving a 14-metre high, dome-shaped, wooden structure seems like a minor point, but it really is not. I do not think I realised what an awesome and awe-inspiring project I was part of, until I was out there, in the middle of the blindingly white ice sheet, and I saw the enormous, black structure moving slowly towards our first stop for the night.

Why are we doing this?

Our field camp NEEM has been inactive since 2012, when the last samples were retrieved from the 2.5km deep borehole. In the following 3 years, scientists and traverse teams have visited the deserted camp occasionally. Now it was time to move everything and start all over on a new drilling project, EGRIP (East Greenland Ice core Project) in Northeast Greenland.

How do you move an entire camp?

In 2012, most of the equipment was packed down on big sledges ready to move, and the dome was fitted with four big skis. The first task this year was to check that everything was in order for the traverse. Let me start by saying that one cannot overestimate exactly how much snow can pile up during three years. The key piece of equipment is therefore a shovel. To be precise, you need a whole bunch of shovels. The two garage tents also had to be taken down. It turned out that they were encased in ice, so add some spades and a couple of sledgehammers to the required equipment.

Freeing the dome

Finally, the skis under the dome had to be freed. The shape of the dome means that the snow drifts around it instead piling up, but the skies under the dome were covered in a mixture of ice and snow. When I look at the photos now, it seems almost unbelievable that we manually cut free and moved away that amount of ice. The piles of ice blocks grew and grew during the two days, where people were working away with chainsaws, shovels and hands to clear the skis. In the meantime, Sverrir, our Icelandic mechanic, displaced tonnes of snow in front of the dome, in order to build a ramp for dragging up the dome.

Freeing the dome using shovels, chainsaws and a pisten-bully. The skies are beginning to emerge from under the dome. The skis support the “bike wheel” (blue) that the dome is mounted on. Credit: N. B. Karlsson.

“It’s going to topple”

I do not think I will ever forget the nerve-wracking moment when the dome was first jolted free. As it moved slightly forward one of the skis lifted completely off the ground, and for a brief, alarming second I thought, “It is going to topple”. Then with a thud, the ski reconnected with the ground and the dome moved slowly up the ramp towards its first stop on the way to EGRIP.

Traversing

Once the traverse started, the days passed in a blur. You get up early, and some days you wait for hours before setting out because there is a problem with one of the vehicles. Other days, everything works perfectly and you scramble to get everything you need out of the dome, before the ladder is hoisted up and the traverse is on its way. Our convoy was a very mixed lot of vehicles; the big Case tractor driven by Pat pulled the dome. Two Pisten-Bullies pulled sledges containing everything from fuel and extra living quarters to our old forklift. Then we had two Flexmobiles, the elderly gentlemen of the convoy, going at a nice, sedate speed, and finally three skidoos, the science teams.

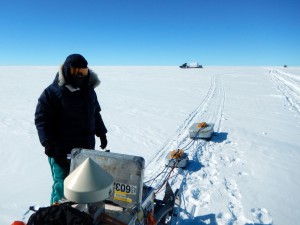

Anna is checking the radar equipment while one of the pisten-bullies is approaching. Credit: N. B. Karlsson.

The freedom of skidooing

Driving a skidoo, we had a lot more freedom than the heavy vehicles. It is easier to make a quick stop on a skidoo and it is often necessary, if there are problems with the equipment. The downside is that it is significantly colder to spend all day on a skidoo than inside a nice, warm cabin. Temperatures were often below -20 degrees Celsius, and although we were fortunate and did not have high winds, it still gets chilly at the end of the day. The solution is to dress warm, in a ridiculous number of layers, and to eat a lot. After a few days we were experts in identifying food that do not freeze easily (salami, fat cheese, brownies), or food that does freeze but is still tasty frozen (smoked halibut, ham).

The Science

At the end of the traverse, Helle, Paul and Sepp had collected numerous samples of the surface snow, dug several metre-deep snow pits and drilled three shallow cores, one of them 15m deep. Simultaneously, Anna and I collected radar data along (almost) the entire traverse route. The data have not been analysed yet but we are looking forward to see the exciting results of our combined efforts.

Helle and Paul are drilling a shallow core while Anna is waiting for the traverse train to pass. Credit: N. B. Karlsson.

Although our traverse is over, the EGRIP project is just beginning. The aim of the project is to investigate the dynamics of fast-flowing ice streams by drilling an ice core through the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream. The EGRIP camp will run until 2020 and next year the camp infrastructure will be set up and drilling will start. Exciting times ahead!

On the traverse we were Dorthe, Helle, Joel, Jørgen Peder, Paul, and myself from CIC (Centre for Ice and Climate, University of Copenhagen, Denmark), Anna and Sepp from AWI (Alfred Wegener Institute, Bremerhaven, Germany), Sverrir, our Icelandic mechanic, Matthias the medic, and Pat Smith from the Greenland Inland Traverse, GrIT, a logistics operations funded by the US National Science Foundation. We were 11 participants, 7 men and 4 women, representing 5 different nationalities, and we had an amazing time!

The project would not be possible without support from the A.P. Møller Foundation, University of Copenhagen, the Alfred Wegener Institute (Germany), Bjerkness Centre (Norway) and the National Science Foundation (USA), who provided staff and a tracked vehicle.

More information:

Read the press release here announcing our arrival at the EGRIP camp.

All our field diaries are available here.

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of The Week – Ballooning on the Ice