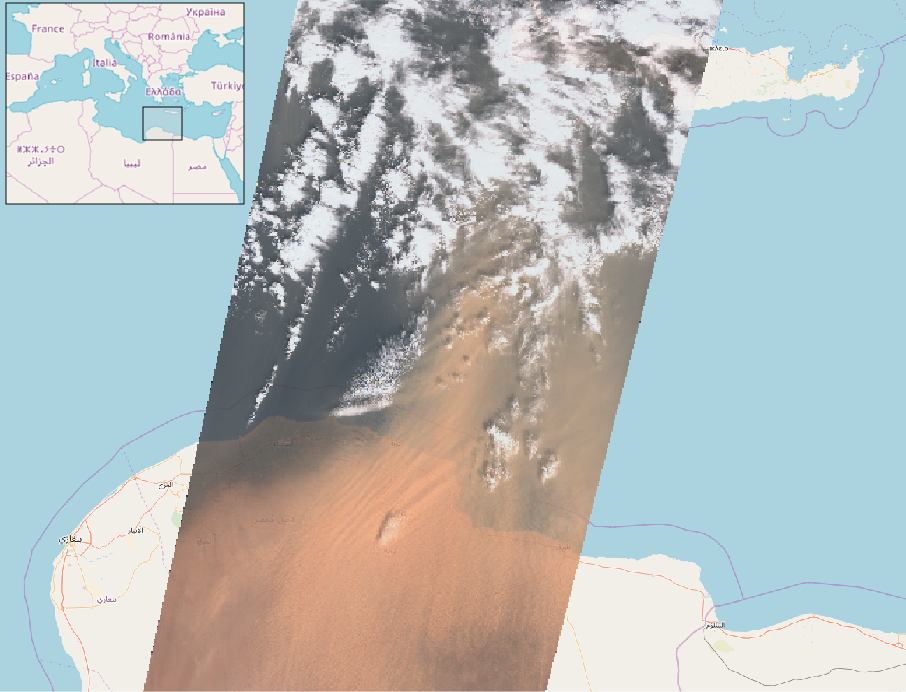

Figure 1. True color composite of a Sentinel-2 image showing the dust plume off the coast of Libya on 22-Mar-2018 (see also on the ESA website) [Credit: processed by S. Gascoin]

On 22 March 2018, large amounts of Saharan dust were blown off the Libyan coast to be further deposited in the Mediterranean, turning the usually white snow-capped Mountains of Turkey, Romania and even Caucasus into Martian landscapes. As many people were struck by this peculiar color of the snow, they started documenting this event on social media using the “#orangesnow hashtag”. Instagram and twitter are fun, but satellite remote sensing is more convenient to use to track the orange snow across mountain ranges. In this new image of the week, we explore dusty snow with the Sentinel-2 satellites…

https://www.instagram.com/p/BgslmE2gPo_/

Sentinel-2: a great tool for observing dust deposition

Sentinel-2 is a satellite mission of the Copernicus programme and consists of two twin satellites (Sentinel-2A and 2B). Although the main application of Sentinel-2 is crop monitoring, it is also particularly well suited for characterizing the effect of dust deposition on the snowy mountains because:

- Sentinel-2A and 2B satellites provide high-resolution images with a pixel size of 10 m to 20 m (depending on the spectral band), which enables to detect dust on snow at the scale of hillslopes.

- Sentinel-2 has a high revisit capacity of 5 days which increases the probability to capture cloud-free images shortly after the dust deposition.

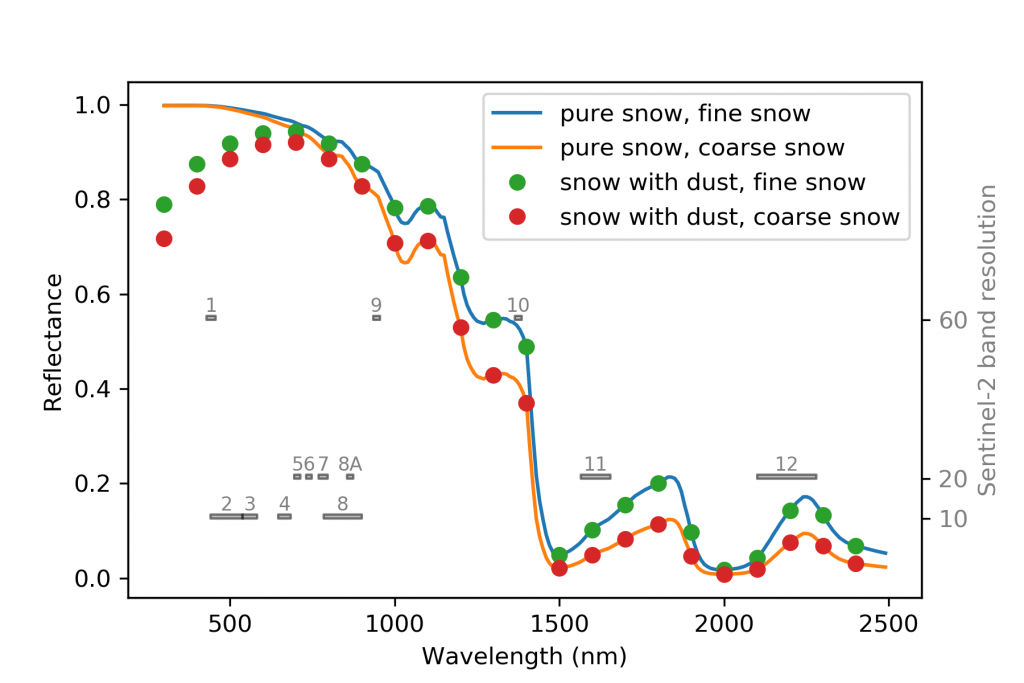

- Sentinel-2 has many spectral bands in the visible and near infrared region of the light spectrum, making easy to separate the effect of dust on snow reflectance — i.e. the proportion of light reflected by snow — from other effects due to snow evolution. The dust particles mostly reduce snow reflectance in the visible, while coarsening of the snow by metamorphism (i.e. the change of microstructure due to transport of vapor at the micrometer scale) tends to reduce snow reflectance in the near infrared (Fig. 2).

- Sentinel-2 radiometric observations have high dynamic range and are accurate and well calibrated (in contrast to some trendy miniature satellites), hence they can be used to retrieve accurate surface dust concentration, provided that the influence of the atmosphere and the topography on surface reflectance are removed.

Figure 2: Diffuse reflectance for different types of snowpack. These spectra were computed with 10 nm resolution using the TARTES model (Libois et al, 2013) using the following parameters: snowpack density: 300 kg/m3, thickness: 2 m, fine snow specific surface area (SSA): 40 m2/kg, coarse snow SSA: 20 m2/kg, dust content: 100 μg/g. The optical properties of the dust are those of a sample of fine dust particles from Libya with a diameter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5) (Caponi et al, 2017). The Sentinel-2 spectral bands are indicated in grey. [Credit: S. Gascoin]

Dust on snow from Turkey to Spain

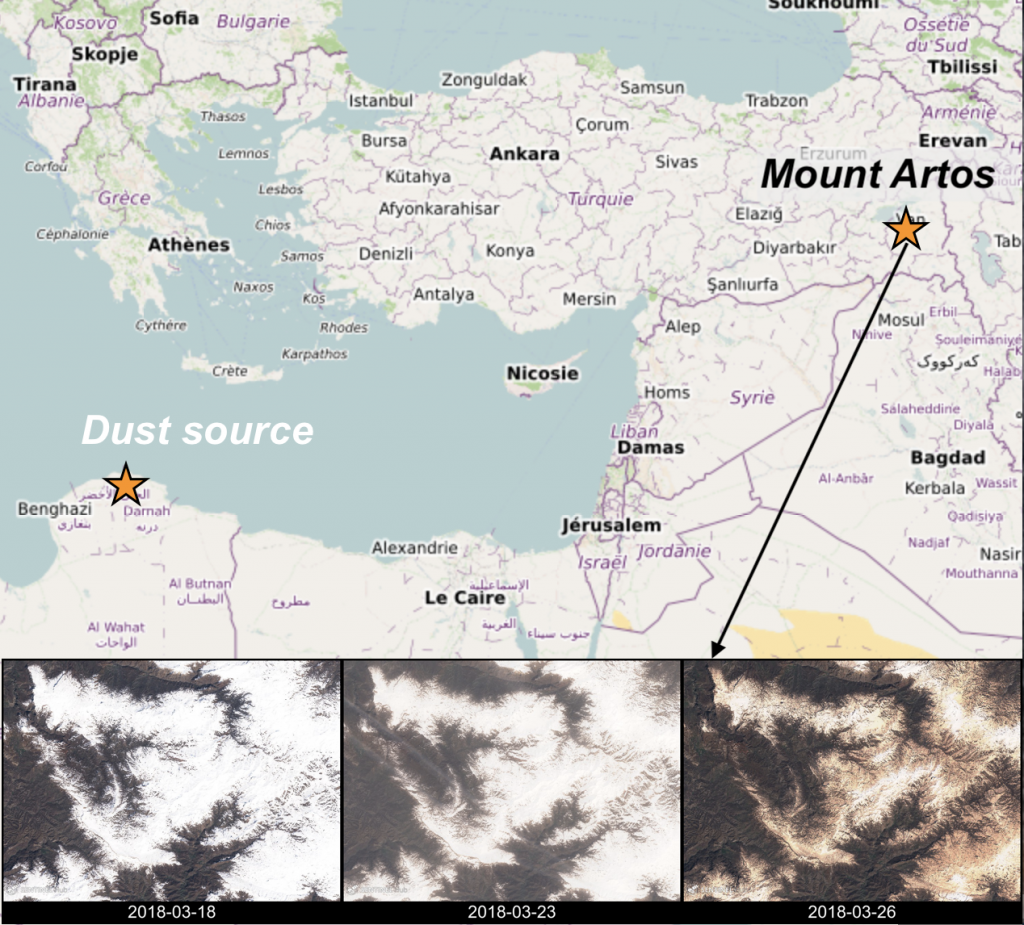

The region of Mount Artos in the Armenian Highlands (Turkey) was one of the first mountains to be imaged by Sentinel-2 after the dust event. Actually Sentinel-2 even captured the dust aloft on March 23, before its deposition (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: Time series of three Sentinel-2 images near Mount Artos in Turkey (true color composites of level 1C images, i.e. orthorectified products, without atmospheric correction). [Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data, processed by S. Gascoin]

Later in April another storm from the Sahara brought large amounts of dust in southwestern Europe.

Figure 4: Sentinel-2 images of the Sierra Nevada in Spain (true color composites of level 1C images). [Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data, processed by S. Gascoin]

This example in the spanish Sierra Nevada nicely illustrates the value of the Sentinel-2 mission since both images were captured only 5 days apart. The high resolution of Sentinel-2 is also important given the topographic variability of this mountain range. This is how it looks in MODIS images, having a 250 m resolution.

Figure 5: MODIS Terra (19) and Aqua (24) images of the Sierra Nevada in Spain. True Color composites of MODIS corrected reflectance. [Credit: NASA, processed by S. Gascoin]

Sentinel-2 satellites enable to track the small-scale variability of the dust concentration in surface snow, even at the scale of the ski runs as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Comparison of a true color Sentinel-2 image and a photograph of the Pradollano ski resort, Sierra Nevada. [Credit: photograph taken by J. Herrero / Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data, processed by S. Gascoin]

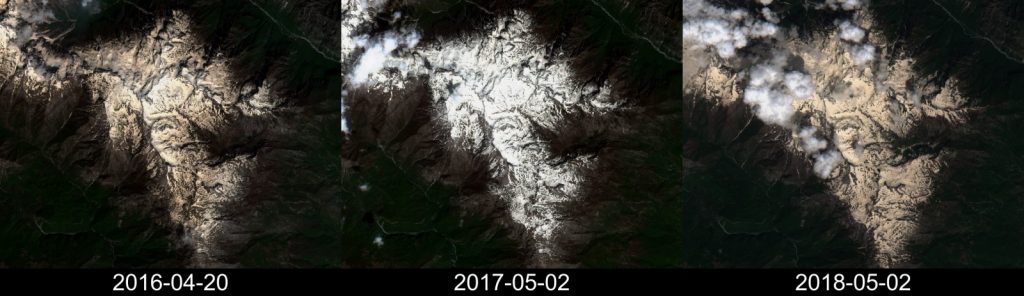

A current limitation of Sentinel-2, however, is the relative shortness of the observation time series. Sentinel-2A was only launched in 2015 and Sentinel-2B in 2017. With three entire snow seasons, we can just start looking at interannual variability. An example in the Prokletije mountains in Albania is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. Sentinel-2 images of the Prokletije mountains in Albania (true color composites of level 1C images) [Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data, processed by S. Gascoin]

These images suggest that the dust event of March 2018 was not exceptional in this region, as 2016 also highlights a similar event. The Sentinel-2 archive will keep growing for many years since the EU Commission seems determined to support the continuity and development of Copernicus programme in the next decades. In the meantime to study the interannual variability the best option is to exploit the long-term records from other satellites like MODIS or Landsat.

Beyond the color of snow, the water resource

Dust on snow is important for water resource management since dust increases the amount of solar energy absorbed by the snowpack, thereby accelerating the melt. A recent study showed that dust controls springtime river flow in the Western USA (Painter et al, 2018).

“It almost doesn’t matter how warm the spring is, it really just matters how dark the snow is.”

said snow hydrologist Jeff Deems in an interview about this study in Science Magazine. Little is known about how this applies to Europe…

Further reading

- Dust on snow in the Armenian Highlands: http://www.cesbio.ups-tlse.fr/multitemp/?p=12998

- Venµs captured the orange snow in the Pyrenees: http://www.cesbio.ups-tlse.fr/multitemp/?p=13172

Edited by Sophie Berger

Simon Gascoin is a CNRS researcher at Centre d’Etudes Spatiales de la Biosphère (CESBIO), in Toulouse. He obtained a PhD in hydrology from Sorbonne University in Paris and did a postdoc on snow and glacier hydrology at the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas (CEAZA) in Chile. His research is now focusing on the application of satellite remote sensing to snow hydrology. He tweets here and blog here.

Simon Gascoin is a CNRS researcher at Centre d’Etudes Spatiales de la Biosphère (CESBIO), in Toulouse. He obtained a PhD in hydrology from Sorbonne University in Paris and did a postdoc on snow and glacier hydrology at the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas (CEAZA) in Chile. His research is now focusing on the application of satellite remote sensing to snow hydrology. He tweets here and blog here.

Marie Dumont is a researcher, leading the snow processes, observations and modelling research team at the snow study centre (CNRM/CEN, Grenoble, France). Her research focuses on snow evolution mostly in alpine region using numerical modelling and optical remote sensing.

Marie Dumont is a researcher, leading the snow processes, observations and modelling research team at the snow study centre (CNRM/CEN, Grenoble, France). Her research focuses on snow evolution mostly in alpine region using numerical modelling and optical remote sensing.

Ghislain Picard is a lecturer working at the Institute of Geosciences and Environment at the University Grenoble Alpes, in the climate and ice-sheets research group. His research focuses on snow evolution in polar regions in the context of climate change. Optical and microwave remote sensing is one of its main tools.

Ghislain Picard is a lecturer working at the Institute of Geosciences and Environment at the University Grenoble Alpes, in the climate and ice-sheets research group. His research focuses on snow evolution in polar regions in the context of climate change. Optical and microwave remote sensing is one of its main tools.