Chilean Patagonia hosts many of the most inhospitable glaciers on the planet – in areas of extreme rainfall and strong winds. These glaciers are also home to some of the most spectacular glacier caves on Earth, with dazzlingly blue ice and huge vertical shafts (moulins). These caves give us access to the heart of the glaciers and provide an opportunity to study the microbiology and water drainage in these areas; in particular how this is changing in relation to climate variations. Our image of this week shows the entrance to one of these caves on Grey Glacier in the Torres del Paine National Park.

“Glacier karstification”

Glaciers in Patagonia are “temperate”, which means that the ice temperature is close to the melting point. As glacial melt-water runs over the surface of this “warm” ice it can easily carve features into ice, which are similar to those formed by limestone dissolution in karstic landscapes. Hence, this phenomenon is called Glacier karstification. It is this process that forms many of the caves and sinkholes that are typically found on temperate glaciers.

From the morphological (structural) point of view, glaciers actually behave like karstic areas, which is rather interesting for a speleologist (scientific cave explorer). Besides caves and sinkholes one often finds other shapes similar to karstic landscapes. For example, small depressions on the ice surface formed by water gathering in puddles, whose appearance resembles small kartisic basins (depressions). Of all the features formed by glacier karstification glacier caves are the most important from a glaciological perspective.

Glacier caves can be divided in two main categories:

- Contact caves – formed between the glacier and bed underneath; or at the contact between extremely cold and temperate ice by sublimation processes (Fig. 2a)

- Englacial caves – form inside the glacier – as shown in our image of the week today. Most of these caves are formed by runoff, where water enters the glacier through a moulin (vertical shaft) and are the most interesting for exploration and research (Fig. 2b)

![Figure 2: Two different types of caves explored on the Grey Glacier. A- Contact formed between the glacier bed and overlying ice [Credit: Tommaso Santagata]. B- Entrance to an englacial cave [Credit: Alessio Romeo/La Venta].](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2016/11/Grey_caves.jpg)

Figure 2: Two different types of caves explored on the Grey Glacier. A- Contact formed between the glacier bed and overlying ice [Credit: Tommaso Santagata]. B- Entrance to an englacial cave [Credit: Alessio Romeo/La Venta].

Exploring the moulins of a Patagonian glacier

Located in the Torres del Paine National Park area (see Fig. 3), the Grey glacier was first explored in 2004 by the association La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche. In April of this year, a team of speleologists went back to the glacier to survey the evolution of the glacier.

![Figure 3: Map of Grey Glacier with survey site of 2004 and 2016 indicated by red dot [Adapted from: Instituto Geografico Militar de Chile ]](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2016/11/Map-300x291.jpg)

Figure 3: Map of Grey Glacier with survey site of 2004 and 2016 indicated by red dot [Adapted from: Instituto Geografico Militar de Chile ]

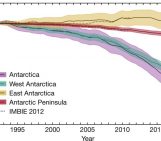

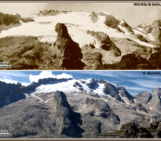

Grey glacier begins in the Andes and flows down to it’s terminus in Grey Lake, where it has three “tongues” which float out into the water (Fig, 3). As with many other glaciers, Grey Glacier is retreating, though mass loss is less catastrophic than some of Patagonia’s other glaciers (such as the Upsala – which is glaciologically very similar to the Grey Glacier). Grey Glacier has retreated by about 6 km over the last 20 years and has thinned by an average of 40 m since 1970.

In 2004 research was concentrated on the tongue at the east of this Grey Glacier (Fig. 3 – red dot), which is characterised by a surface drainage network with small-size surface channels that run into wide moulin shafts, burying into the glacier. In this latest expedition, the same area was re-examined to see how it had changed in the last 12 years.

Several moulins were explored during the 2016 expedition, including a shaft of more than 90 m deep and some horizontal contact caves (Fig 2). The glacier has clearly retreated and the surface has lowered a lot from the 2004 expedition. The extent of the thinning in recent years can be easily measured on the wall of the mountains around the glacier. Interestingly the entrance to the caves which were explored in 2004 and in 2016 was in the same position as 12 years ago, although the reasons for this are not yet clear.

The entrance of two of the main moulins which were explored were also mapped in 3D using photogrammetry techniques (see video below). The 3D models produced help us to better understand the shape and size of these caves and to study their evolution by repeating this mapping in the future. For more information about the outcome of this expedition, please follow the Inside the Glaciers Blog.

Further Reading:

- Alessio Romeo’s stunning photography of Grey Glacier.

- La Venta Patagonia Project Information.

- Information and results from a similar project on Gornergletscher, Switzerland.

Books on the subject:

- Caves of the Sky: A Journey in the Heart of Glaciers, 2004, Badino G., De Vivo A., Piccini L.

- Encyclopaedia of Caves and Karst Science, 2004, Editor: Gunn J.

Edited by Emma Smith and Sophie Berger

Tommaso Santagata is a survey technician and geology student at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. As speleologist and member of the Italian association La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche, he carries out research projects on glaciers using UAV’s, terrestrial laser scanning and 3D photogrammetry techniques to study the ice caves of Patagonia, the in-cave glacier of the Cenote Abyss (Dolomiti Mountains, Italy), the moulins of Gorner Glacier (Switzerland) and other underground environments as the lava tunnels of Mount Etna. He tweets as @tommysgeo

Tommaso Santagata is a survey technician and geology student at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. As speleologist and member of the Italian association La Venta Esplorazioni Geografiche, he carries out research projects on glaciers using UAV’s, terrestrial laser scanning and 3D photogrammetry techniques to study the ice caves of Patagonia, the in-cave glacier of the Cenote Abyss (Dolomiti Mountains, Italy), the moulins of Gorner Glacier (Switzerland) and other underground environments as the lava tunnels of Mount Etna. He tweets as @tommysgeo

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Seafloor secrets: traces of the past Patagonian ice sheet