The 30th August 2016 marks 100 years since the successful rescue of all (human) member of Shackleton’s Endurance crew from their temporary camp on Elephant Island (see map). Nearly a year prior to their rescue they were forced to abandon their ship – The Endurance – after it became stuck in thick drifting sea ice, known as pack ice, trying to navigate the Weddell Sea. It was the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration and was well documented by Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer. Our post today brings you some of the stunning images he took over 100 years ago!

The Endurance

In August 1914 Ernest Shackleton set out with a crew of 27 men (chosen from over 5000 who applied!) on the ship Endurance, as part of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Their mission was to complete the first land crossing of Antarctica – from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea via the South Pole. Unfortunately disaster struck the Endurance in January 1915 when it became stuck fast in pack ice in the Weddell sea. True to the ships name the crew were forced to endure a very long journey home!

Our image this week shows the Endurance finally sinking through that pack ice into the depths on the ocean on the 21st November 1915, after being stuck in the pack ice for 10 months. Luckily, due to the fact it had been interned for such a long time, no members of the crew were on-board and much of the cargo had been removed, leaving the crew with food supplies and three small whaling boats to continue their journey.

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.

E. Shackleton’s advertisement for his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (source: Watkins, 2012, p.1)

The long journey home!

Frank Hurley (expedition photographer) and Ernest Shackleton at camp. First published in the United States in Ernest Shackleton’s book, South, in 1919., via Wikimedia Commons.

On the 27th October 1915, shortly before the Endurance sank, Shackleton had given the order to abandon ship. The crew started to march towards open ocean pulling two of the whaling boats filled with supplied behind them. After a few days it became apparent that it was too difficult to move and the crew established a camp on the ice floe, know as “Ocean Camp”. At their camp on the ice the ship’s crew slept in tents but the dogs were housed in “dog igloos”. From this position supplies (including three whaling boat) were retrieved from Endurance, before she finally sank in November 1915.

Over the next few months the crew attempted further relatively unsuccessful marches to the ocean before eventually establish “Patience Camp” in December 1915 on the ice – which would be their home for more than three months. By April 1916 the ice floe had broken up and all 28 men piled into their three boats to head for Elephant Island which they successfully reached 5 days later. However, their journey was not yet over!

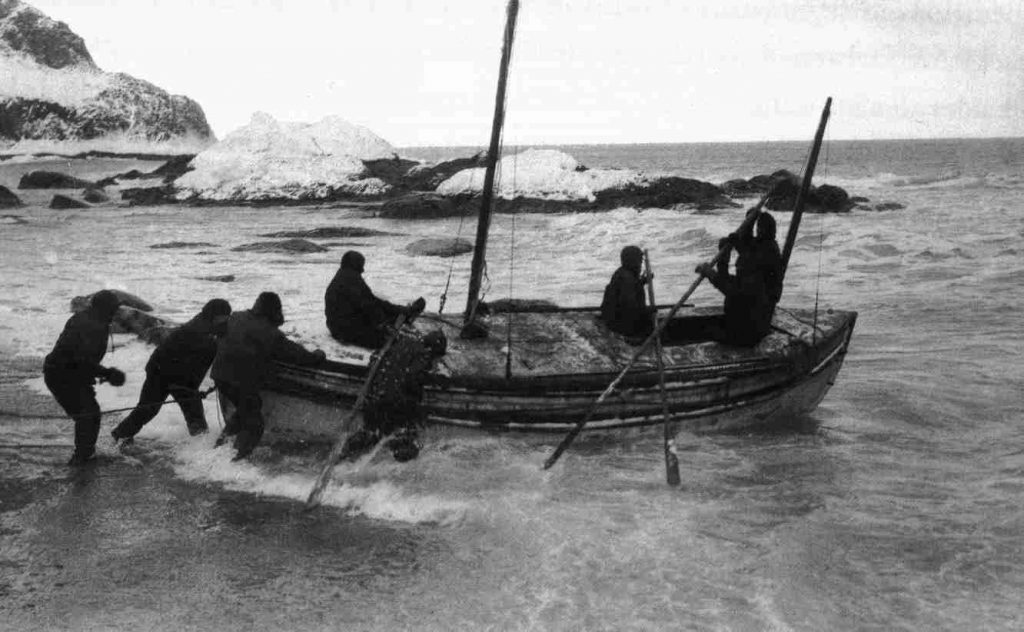

Elephant island was very remote and uninhabited with no real possibility of rescue, especially considering it was the middle of the first world war and many ships capable of making the journey from England were occupied in battle. Realising they needed to find their own assistance Shackleton and a skeleton crew of 5 men set sail in one of the small whaling boats, The James Caird, for a perilous 1,500 km journey to South Georgia where there were known to be inhabited whaling stations. They eventually landed safely on South Georgia a few weeks later, only to discovered they were on the opposite side of the island to the whaling station they had been counting on for help. Shackleton and 2 of his men set off on a 36-hour trek to reach Stromness whaling station, where they were eventually able to raise the alarm on the 20th May 1916. First they rescued the remainder of the 5 man crew from the other side of the South Georgia and then set out to rescue the remaining crew Elephant Island.

The launching of the James Caird from Elephant Island, in an attempt to reach the South Georgia. Photo Credit: Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer via Wikimedia Commons.

It wasn’t until the 30th August 1916 that the men on Elephant Island were rescued, having spent over 4 months stranded there during the harsh Antarctic winter. Shackleton had made four attempts to rescue them, starting on 22nd May 1916, just three days after he had arrived in Stromness, however, each attempt had been thwarted by sea ice surrounding the island. Finally Shackleton managed to reach his crew in Yelcho, a small steam tug loaned to him by the Chilean government. He found all the men in a bad condition but alive, sadly the same cannot be said of the 69 dogs. Some of which died from ill health and many of which were eaten by the crew to survive those first months stranded on the ice.

![A timeline and map showing the journey of the Endurance crew. Image credit: Luca Ferrario, DensityDesign Research Lab. CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/cr/files/2016/08/Imperial_Trans-Antarctic_Expedition_map_and_timeline.svg-1.jpg)

A timeline and map showing the journey of the Endurance crew. [Image credit: Luca Ferrario, DensityDesign Research Lab, via Wikimedia Commons.]

Where is The Endurance now?

Good question! There is a plan afoot to use Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) to dive down to the sea floor and try to locate and film the remains of the Endurance, no firm details of the current state of this expedition seem to have been released yet, but it may be worth keeping your eyes on their twitter feed @IceProjectShack.

It still happens today!

On Christmas Day 2013 the Russian vessel the M.V. Akademik Shokalskiy got stuck in pack ice while returning from East Antarctica with a crew of scientists, media, and students onboard. Everyone was eventually rescued safely by collegues from China and Australia – unlike Shackleton’s era there is now a lot more support when people get into difficulty in Antarctica. However, a photographer onboard, Andrew Peacock noted that:

We have learned from nature, as humankind always does, that it’s possible to be caught by an unexpected and not predicted situation.

It seems that while the likelihood of rescue has improved over the past century, that we mere mortals are still at the command of nature!

Further Reading

- The Scott Polar Research Institude Shackleton Archives: http://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/archives/shackleton/

- The Shakleton Foundation: http://shackletonfoundation.org/about/sir-ernest-shackleton/

- Wikipedia’s Page on the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Trans-Antarctic_Expedition

- In search of the Endurance website: http://ice-shackletonmovie.com/in-search-of-the-endurance-imax-documentary/

Edited by Sophie Berger

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Image of the Week — Looking back at 2016

Pingback: Cryospheric Sciences | Radiocarbon rocks! – How rocks can tell us about the history of an ice sheet…