In the frozen expanse of Antarctica, where the remote environment tests the limits of scientists, a unique relationship between science and art can emerge. As the isolation, weather and beauty of the ice-covered continent introduce themselves, some Antarctic individuals find solace in the realm of art. In this blog post, we delve into the interplay between the world of scientific exploration and the creativity. We uncover the significance of antARcTica, where the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the creativity coalesce.

Art for hope: Professor Marianne Karplus, Geophysicist

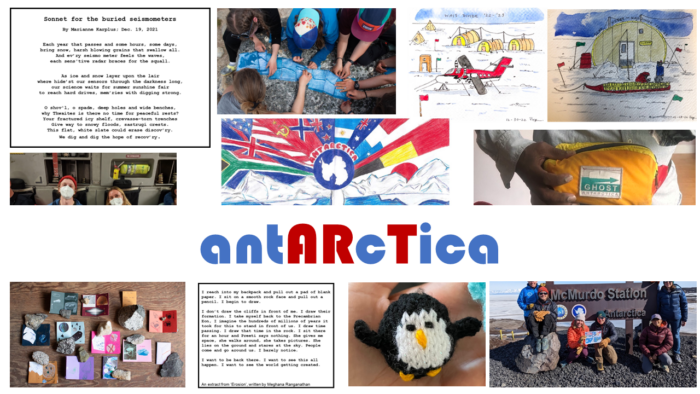

Marianne Karplus is a well-seasoned Antarctician, having been to Antarctica for multi-month field seasons 3 of the last 5 years! As a co-PI of the ITGC Thwaites Interdisciplinary Margin Evolution (TIME) project, evaluating the role of shear margin dynamics in the future evolution of Thwaites drainage basin, Marianne is well practiced in the art of patience and adaptability. Last season, the TIME project working out of McMurdo research station in Antarctica was disrupted by a series of Covid outbreaks, unseasonably bad weather (even for Antarctica!) and other logistical challenges. As such, Marianne reached out to art for a sense of hope:

I enjoy creative writing such as poetry as a way to capture and communicate experiences in a different way. I think in Antarctica, when things are quite busy and stressful, the structure of the sonnet is appealing as a framework. Sonnets also have a lyrical and musical form, sometimes with a sense of longing, which feels appropriate for Antarctic experiences.

Figure 1: Members of the Thwaites Interdisciplinary Margin Evolution (TIME) team excavate a seismometer after a two-year deployment on Thwaites Glacier. [Photo & Art Credit: Marianne Karplus]

Art as a community: Professor Sridhar Anandakrishnan, Geophysicist

Sridhar Anandakrishnan first visited Antarctica in 1985 and has just completed his 23rd (!!!) visit as part of the ITGC GHOST project. As a seasoned visitor and individual from a minority background, Sridhar understands the importance of community in the continent. Over the years, he has witnessed the continents community change but not necessarily for the better.

Over the years in Antarctica, things have changed quite a bit! On the positive side, the facilities are better; the environmental practices are much better (recycling, removing waste). Communication to the outside world is better. But one thing that hasn’t is the racial and ethnic diversity there. There is clear improvement in gender diversity, with women and LGBTQ+ folks much more present, open, and comfortable (though there are clearly still deep-seated issues of harassment and threats that continue to plague all the Antarctic programs). But people of color remain underrepresented. All of this is to say that systemic change can and must come to Polar research, but change is slow.

Sridhar therefore spends time highlighting the racial diversity crisis in Antarctic field work and building a sense of community on station, which he does through Art.

Before the disastrous Covid delays of 2022/23, I sewed a few things – but during that time, sewing was a real gift – both as a way to keep occupied, but more importantly as a way to interact with station folks in a casual and non-work setting – something that is unfortunately rare. The bag I made was ridiculously amateur-ish but I was quite proud of it! Since then, I have really gotten into sewing and have gotten better at it (so one good thing came out of the covid nonsense in McMurdo).

I love sewing – I find it to be soothing, focuses the mind, and is practical – and makes for great gifts. Plus, for field scientists, sewing is an underappreciated essential skill! So much of our kit would benefit from personalization – and if you can sew you can fix things that rip or tear.

Figure 2: A cleverly crafted bag made from the scraps of old tent material used in Antarctica. [Photo credit: Sridhar Anandakrishnan]

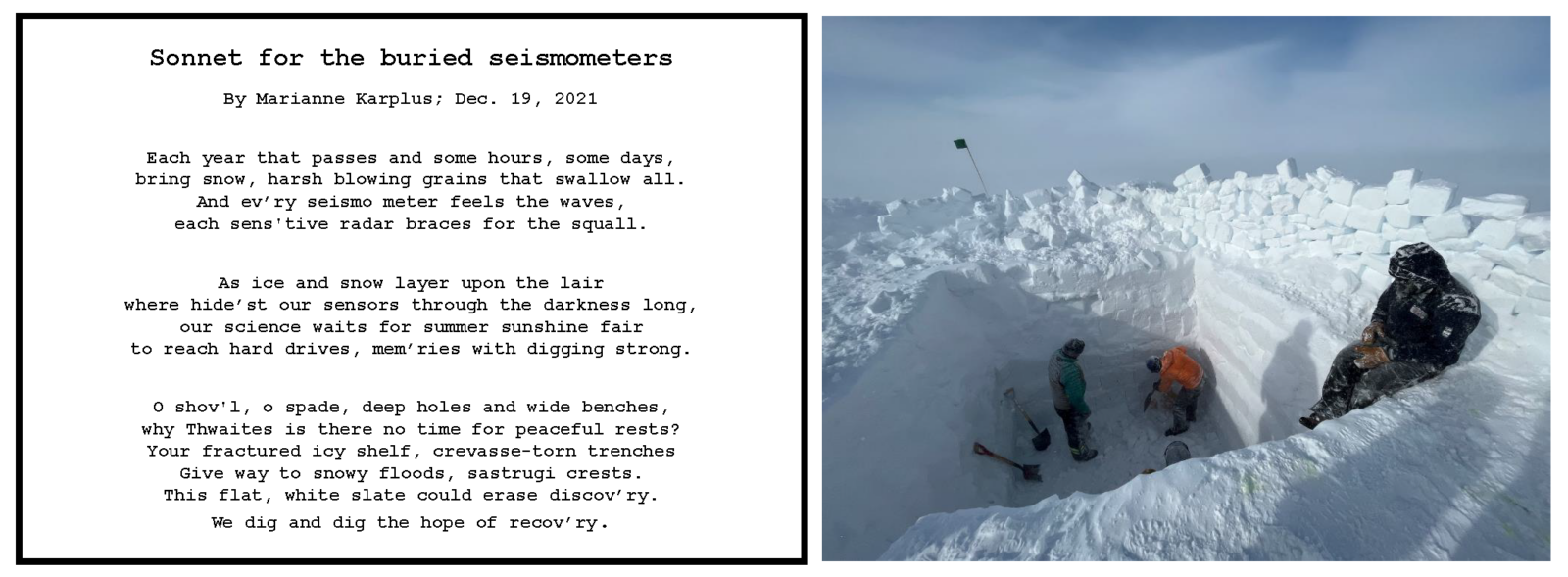

Art as a memory: Pepper Cook, Winter Lead of Search and Rescue

Pepper Cook is a jack of all trades. An individual who signed up to go to the continent for the summer season after spending several years eyeing up job descriptions, waiting for one with adventure in the deep field. After six months as part of the ‘groom team’, a team of individual’s who fly to remote places in Antarctica and ensure the area is ready to have large airplanes and cargo be delivered, she decided that her time on the continent wasn’t ready to come to an end. Pepper ended up staying 6 more months as part of the small wintering team at McMurdo in Antarctica who say goodbye to daylight and hello to the very cold conditions of winter on the continent. She took on the role of lead of Search and Rescue and made sure to capture the memories she made in watercolour form.

Figure 3: Watercolour paintings from Pepper Cook’s time at WAIS divide over the winter season. [Photo & Art Credit: Pepper Cook]

Watercolor painting is a great field hobby for me for so many reasons! It’s lightweight, cheap, and I find it to be super meditative and a great use of downtime when you’re somewhere with not many books and no ability to use phones. To capture something in watercolor you have to observe the scene for a long time, and I find it makes little details cement in my memory better. It’s also trained my eyes to see color better- a sunset used to just look pink to me, but now I’m more able to pick out the yellows, reds, purples, and oranges (not that we had any sunsets in Antarctica last season!). It’s also a fun quick gift to leave behind when you make special new friends, and is easy to give quick tutorials to help friends try something new.

Pro tip: in the field when it’s very cold, you can mix a couple of drops of clear alcohol like gin or vodka in with your water to keep it from freezing…but don’t forget to taste test it first 😉.

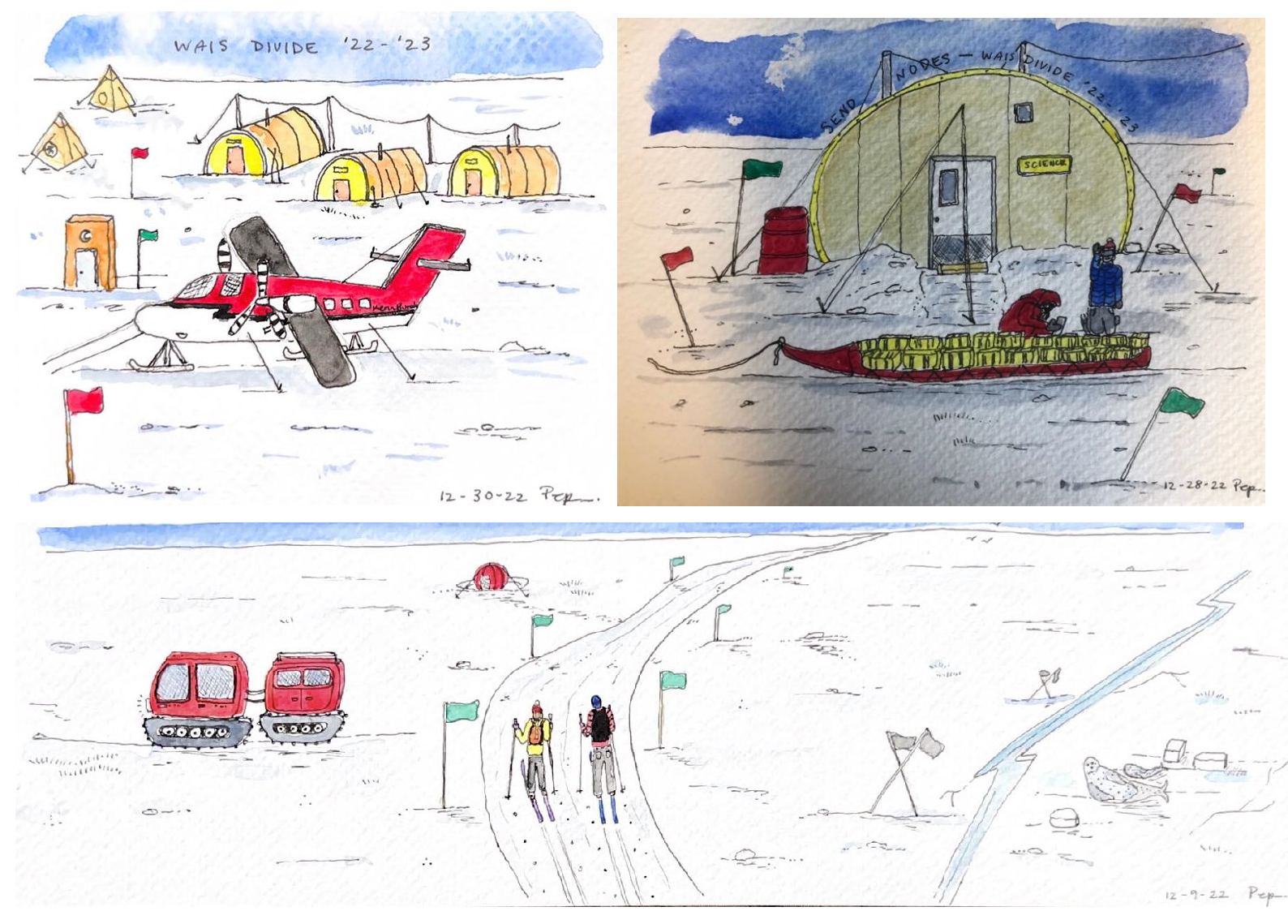

Art as mindfulness: Madeline Hunt, Polar Engineer

Madeline Hunt is any scientists dream companion in Antarctica. As a polar engineer she had the ability to fix and find anything you might need for your scientific equipment that had inevitably broken enroute to Antarctica. Most importantly, she had a secret stash of Duct tape and Sharpies, deceptively valuable assets down South! She was always busy, whether it be taking a helicopter to Mt Erebus, an active volcano in Antarctica with seismic stations on it that needed maintaining, or going to the ‘deep field’ with science teams and ensuring all equipment worked smoothly during their deployment. Madeline would never be caught not smiling and happy, and she explains how art helped with this:

Making time to draw in my sketchbook is important for me as a set time for me to take some space to get out of my head and focus on how I am feeling. This is especially useful in in high stress situations when I’m expected to be constantly “on” and focused, and emotional times (like when the Antarctic flight schedule is constantly changing).

Figure 4: Crocs of a field scientist resting after a long day in the field [Photo & Art credit: Madeline Hunt]

Art as a connection: Emma Pearce, Geophysicist

Emma Pearce is a researcher in glacier geophysics, but finds creativity, crafting, and art in any form her passion. A trip to Antarctica for Emma is a chance to finish all those projects that have fallen to the bottom of the pile after a much more fun, new, shiny craft project has made itself known. For Emma, in previous seasons, this has included finally finishing knitting the eight legs of a giant squid, embroidering a map of Antarctica, and crocheting together the many squares of a patchwork blanket. This season, she took the time to make some things a little bit smaller:

When on fieldwork, you are often far away from loved ones for months at a time with little to no communication. This normally means calling them when you can on crackled satellite phone or sending 160-character texts via sat phones. For some, myself included, this means we find alternative ways to feel connected to those we love, which for me is usually through a form of art or creativity. Last season, I spent my time in the field knitting tiny penguins for family members, embroidering symbols of our Antarctic season, and knitting hats. Not only was this a way to feel connected to those you miss, it was a great way to bond with fellow scientists by teaching them new skills.

Figure 5: Left: Avid knitters Ronan Agnew and Emma Pearce bonding on the C17 flight south to Antarctica. Right: creating tiny penguins to send to loved ones. [Photo & Art Credit: Emma Pearce]

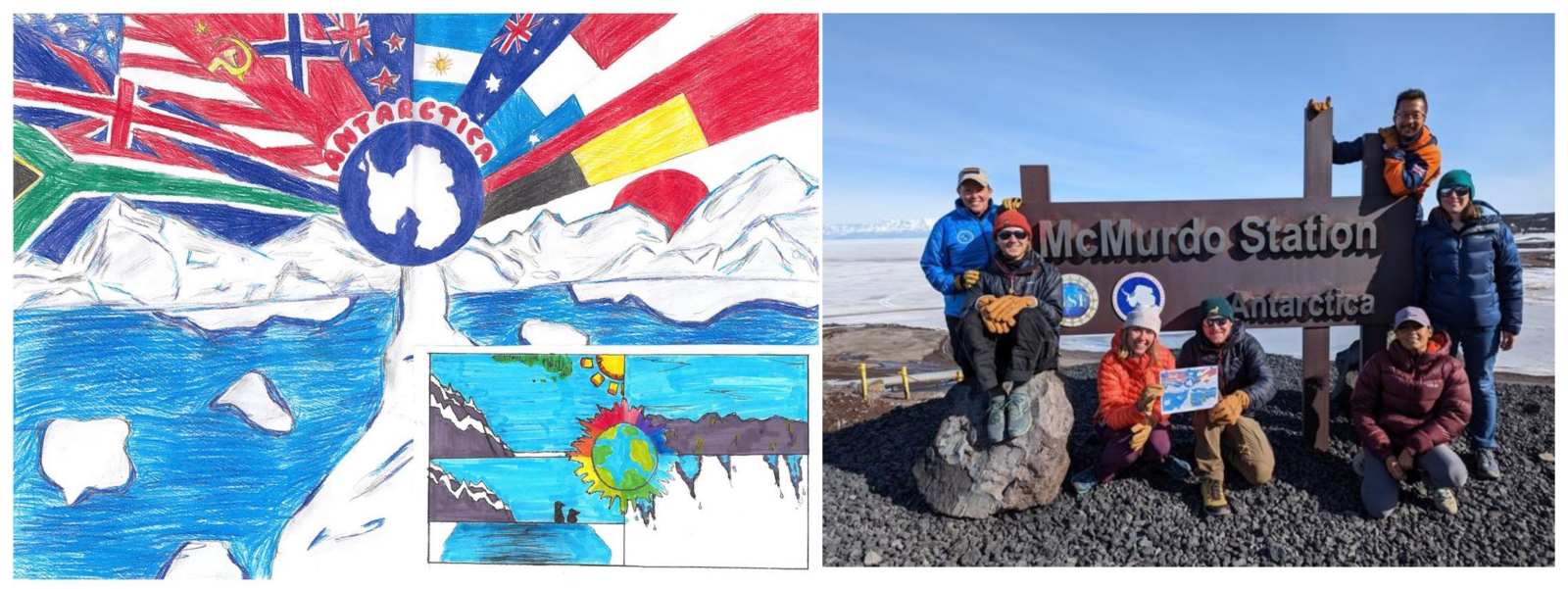

Art for outreach: Antarctic Flags scheme, Fiona Old

Fiona Old is the Co-head of Education and Outreach & Antarctic Flags Coordinator, whilst also being the Head of Geography at a college in the UK. An enthusiastic individual who understands the importance of outreach within the scientific community, Fiona talks about one of the projects she leads, the Antarctic Flag project with the UK Polar Network:

The Antarctic Flags project run by the UK Polar Network is a brilliant outreach activity for schools across the world. Students design their own flag for Antarctica and these are taken south by a team of volunteers from a variety of Polar Institutes and programmes including BAS, USAP and INACH. In 2022, over 300 flags were sent to Antarctica and photographed by our volunteers, and schools across the world including schools in the UK, Turkey, USA, UAE, Poland and Spain were able to share photos of their artwork in Antarctica. This is an incredibly success project. It is open to students of all ages, and it is a brilliant way for students to learn more about Antarctica. I have led the team now for three years and it has been wonderful to see the beautiful designs each year and I love receiving the photos to send back to schools, sharing the journeys of their flags.

Figure 6: Scientists at the US research station McMurdo, posing with the Antarctic flag. [Photo credit: Emma Pearce]

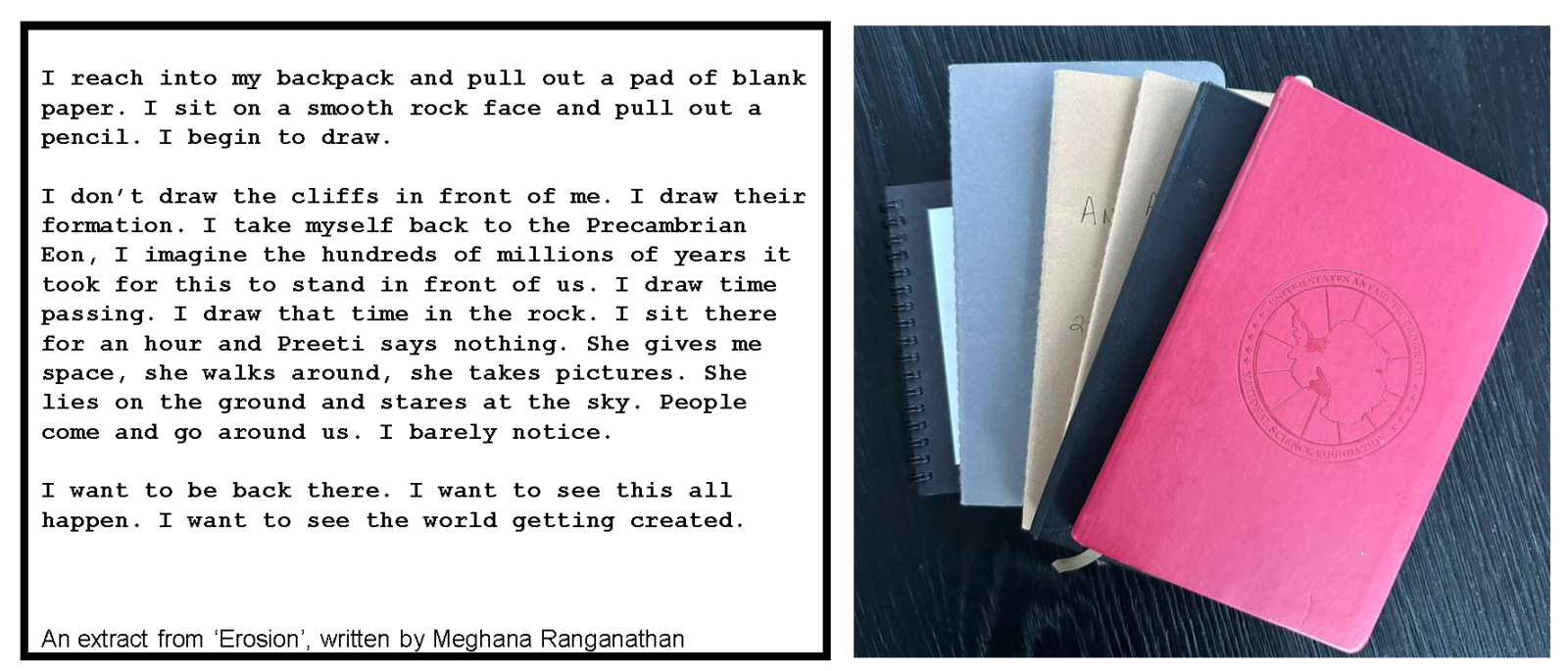

Art for mindfulness: Meghana Ranganathan, Geoscientist

Meghana had a very exciting and unexpected trip to Antarctica in 2022. As a reserve for the field season, with only 24 hours to go before the flight was due to leave, she had accepted that this year she would not be seeing her first penguin. How wrong she was! One phone call later, and a mad dash to gather her supplies, she was on a flight south for a four-month visit, with less than 18 hours’ notice. Having just finished authoring her first novel, writing has always been an important part of Meghana’s life which she balances whilst also being a full time Assistant Professor in geoscience. As such, it naturally also became an important part of her life in the field.

It’s a common thought that science is purely analytical. That science is done step-by-step, rigidly following “the scientific method”, the direction laid out clearly and the scientist following the path without veering. The actual practice of doing science is deeply creative, and involves wandering in and out of various ideas, and I have found that tapping into that creativity outside of science has sparked an energy that has greatly enhanced my scientific work. My goal is to tell stories about the past and the future of earth systems, and I can do that through mathematics and physics, and also through writing. Journaling and creative writing, for me, has allowed me to process science and being a scientist in a different perspective, and it has been immensely useful for understanding my work and myself.

Figure 7: An extract from Meghana’s “Erosion” left and a photo of the journals she took to her Antarctica field trip right [Photo Credit: Meghana Ranganathan]

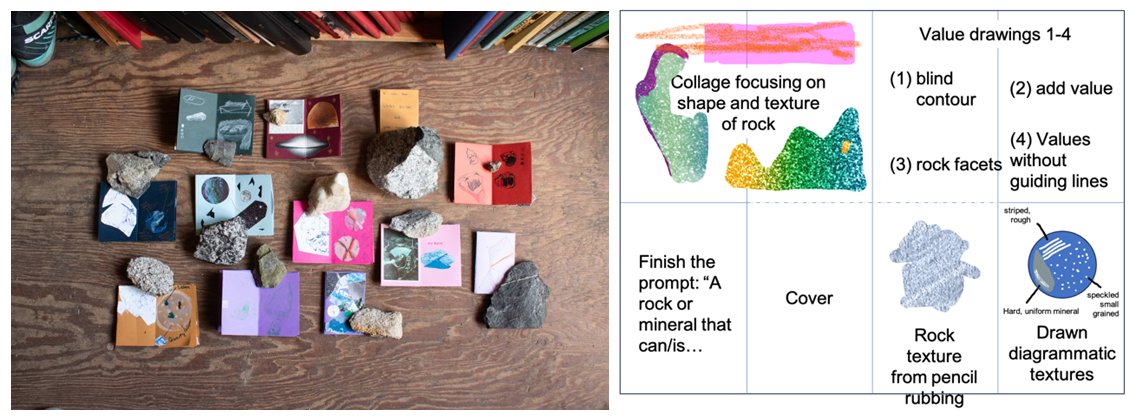

Art for education: Elizabeth Case, Geophysicist

Elizabeth Case understands perfectly how to integrate art, outreach, and science to complement one another. This shows through their project Cycle for Science, which Elizabeth is a co-founder of, a successful outreach program that translates science into the hands-on K-12 lessons. Elizabeth is now working with artists including Hannah Mode to further investigate how art and education can be combined within the world of glaciology.

The Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP) takes students across the icefield over 8 weeks to learn about mountaineering and polar research. I have taught on the program for three of the last six summers, starting in 2018. Last season, in summer 2023, artist Hannah Mode and I built a series of workshops that taught art and science together based on the shared desire for more interdisciplinary, feminist, embodied learning and teaching in the natural sciences. We ran two concurrent workshops: one, focused on photogrammetry and printmaking, and another on geology and drawing.

In the first, students learned how to do drone surveys, mapping a supraglacial lake system on the Taku Glacier (Figure 8) and using these images to create a digital orthomosaic and DEM of the glacier surface. In conjunction, we had students print part of the survey onto fabric prepared with a cyanotype solution, a photosensitive chemical that turns blue when exposed to UV light. The students took these prints and puzzled the images together, finding the points of overlapping features (tie points) and stitching them together using embroidery stitches like box stitches, small flowers, and crosses This made one part of photogrammetry – finding tie points and stitching images together into an orthomosaic – more tangible, and ultimately produced a five-foot long tapestry (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Left: Taku Glacier.. Right: Students tacking together prints of the Taku Glacier printed onto fabric. [Photo credit: Elizabeth Case]

In the second, a workshop called Story of a Rock first conceived by Hannah Mode and Ben Huff, students learned about the geology of the Juneau Icefield in the morning, and then applied this learning to drawing and zinemaking in the afternoon. For the latter, students chose a rock and went through a series of exercises to learn how to draw an object through close observation (Figure 9). Each student completed these exercises in a small booklet, called a zine, made from a single page of paper. This provided students both with the tools to make their work, and a completed object to carry with them for the rest of the season (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Left: Students chose a rock and learnt how to draw an object through close observation. Right: A ‘zine’ created by the students from their rock observations. This provided students both with the tools to make their work, and a completed object to carry with them for the rest of the season. [Photo Credit: Elizabeth Case]

These examples of Art in Antarctica only touch the surface of the creativity that intertwines and enables the scientific achievements of the continent. Whether it be poetry, painting or creating, Art is fundamental to the success of our science.

Written by Emma Pearce, Edited by Vio Coulon & Maria Scheel

Sleeves Digitizing

I’ve read your blog. Honestly I’ve never read this type of blog before. Appreciate your work and will love to read your incoming articles too.

Meilleur Chirurgien Rhinoplastie

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing