It’s long been recognised the peoples of European prehistory occasionally, and quite deliberately, melted the rocks from which their hilltop enclosures were made. But why did they do it? In today’s blog post Fabian Wadsworth and Rebecca Hearne explore this question.

Burning questions

Throughout the European Bronze and Iron Ages (spanning 2600 years from 3200 BC to 600 BC), people constructed stone-built, hilltop enclosures. In some cases, these stone walls were burned at high temperatures sufficient to partially melt them. These once-molten forts are called vitrified forts because today they preserve large amounts of glassy rock. First described in full in 1777, the origins and functions of these enigmatic features have been the subjects of centuries of debate.

Today, researchers generally agree that the glassy wall rocks are the result of in situ exposure to high temperatures in prehistory, similar in magnitude to those temperatures found in volcanoes on Earth. This was sufficient to partially or wholly melt the stonework, and the resulting melts are preserved as glass upon cooling.

There are still many outstanding questions concerning vitrified enclosures and forts, but the most immediate and arresting are: how and why were they burned?

Vitrified fort walls are mostly found in Scotland and are built from a diverse range of rock types

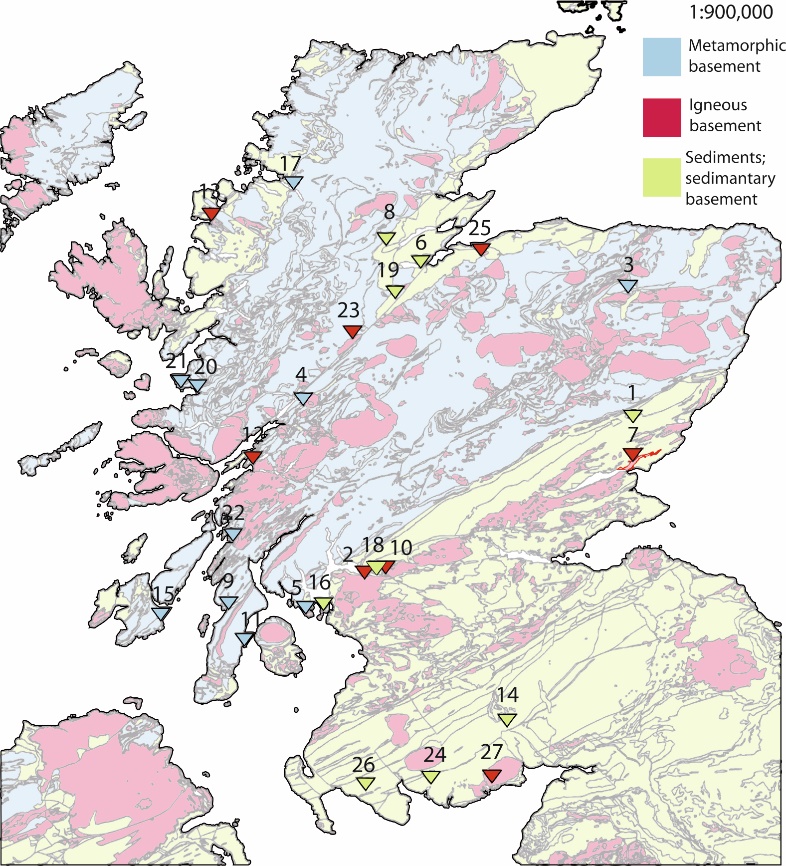

Vitrified enclosures occur throughout Europe but the best known examples are found in Scotland. Using the compilation created by Sanderson and co-workers (link provided below) we can map the distribution of forts, categorized by the rock-type from which they were built, and compare this with a simplified geological map of Scotland (from the British Geological Survey; Image 1). This shows that the building stone used in fort walls is not always the same and was more likely to be found locally.

Map of Scotland with simplified basement geology and cover-sediments marked. Vitrified fort positions are numbered such that 1- Finavon, 2- Craig Marloch Wood, 3- Tap O’North, 4- Dun Deardail, 5- Dunagoil, 6- Craig Phaidrig, 7- Laws of Monifieth, 8- Knockfarrell, 9- Dunskeig, 10-Dumbarton Rock, 11- Carradale, 12-Dun MacUisnichan, 13- Art Dun, 14- Mullach, 15- Trudernish Point, 16-Cumbrae, 17- Dun Lagaidh, 18- Sheep Hill, 19-Urquhart Castle, 20- Eilan-nan-Gobhar, 21- Eilan nan Ghoil, 22- Duntroon, 23- Torr Duin, 24- Trusty’s Hill, 25- Doon of May, 26- Castle Finlay, 27- Mote of Mark. (From the British Geological Survey).

How hot? How long?

A key question surrounding the melting and glass-formation processes that occur to form vitrified fort walls is what temperature was required and how long must the fires have burned? As we know, the required minimum temperature for melting rocks is the solidus, which varies by hundreds of degrees from rock-type to rock-type. Above the solidus, the partial melt fraction will increase until the material liquidus, above which all components of the rock are molten. In mineralogically diverse rocks, the partial melt fraction between the solidus and liquidus not only increases, but changes composition. Pioneering investigations of vitrified fort wall materials (for example, by Youngblood and co-workers) and others have explored this by looking at the composition of the glass that is formed when the partially molten fort walls are cooled. The composition of these materials and an understanding of the thermodynamics of the melting process yields temperatures of the prehistoric fires in question. Youngblood and colleagues found that temperatures were likely to be, on average, 900-1150 ºC.

In a recently published study, we used a different technique in an attempt to answer the same question. Samples of fort walls from Wincobank vitrified hillfort, Sheffield, UK, were used in high-temperature tests to measure the melting process in situ. We measured the amount of each mineral phase as it decreased above the solidus. This technique allowed us to extract additional information that previous investigators have not been able to probe. As well as suggesting a temperature window within which melting occurs, we were able to find the timescale of burning required to achieve the degrees of partial melting seen within Wincobank’s vitrified enclosure wall. Wincobank was constructed from a local sandstone; we found that the quartz in this sandstone was steadily removed upon experimental heating, matching the final quartz content of the enclosure wall rocks at a temperature window of 1050-1250 ºC for burning events of more than 10 hours.

When taken together, such investigations of the conditions required to form glass in prehistoric enclosure walls can more reliably inform the debate about why the fires were set in the first place. If glass is consistently found around a fort’s circumference (as is often the case, particularly in Scotland), and its particular building stone type dictates a heating event requiring a duration of 10 hours or more at peak temperature, it seems unlikely to us that such walls were burned accidentally or during periods of conflict or events of warfare (see below). In that case, if the enclosure walls were burned deliberately by the occupants, the outstanding question remains: why?

Why set fire to a stone wall?

In any archaeological investigation, a key goal is to attempt to explore and extrapolate the beliefs, motives, and desires of people in antiquity from their material culture. For practitioners of any discipline this is no easy task, with subjective interpretation of evidence and difference of opinion often resulting in vibrant discussion!

Consequently, numerous possible prehistoric motives for burning a fort wall to the point of melting have been posited. First is the possibility that the fires were lit during enemy attack or some other act of violence (mentioned above). Second, there’s the possibility that the fires were a product of deconstruction of the fort walls at the end of occupancy. Third, the conflagration was part of a ritual or display of prestige. Finally, there is the possibility that the fires were set with the intention of strengthening the stonework during construction. Each of these explanations has received attention; however, the last option had, until recently, been dismissed by previous researchers as largely unlikely, once it was recognised that heating rocks in general weakens them by the proliferation of microcracks from thermal stresses.

We revisited the idea that fort walls could have been burned during the construction in order to strengthen them. In our latest work we explored this in a simple way by showing that while the blocks in a fort wall will get weaker during high temperature burning, the more fine-grained rubble interstitial to these blocks will get much stronger. This strengthening occurs simply because the fine grained materials between larger blocks can fuse together by sintering when they are partially molten. And indeed, it is so often reported that large blocks are surrounded by a glassy mass that is fused to them (we show this in Image 2 from Wincobank fort, Sheffield, U.K.). We pointed out that this is contrary to the conventional view that fort walls must be weakened by the fires.

A block from the Wincobank enclosure wall in Sheffield, UK. This piece shows the typical feature where fine grained glassy material is welded to the larger, less altered blocks. In detail, this demonstrates that thermal gradients resulting from heating blocks of different sizes play an important role in determining which blocks melt and weld, and which blocks do not. (Credit: Fabian Wadsworth)

The debate rages on

We acknowledge that the strengthening effect does not rule out other motives. Indeed, the strengthening may be incidental to the true motive for the wall burning. It is also important to take into account the fact that, in many of the known examples of vitrified enclosures, where dated, the burning event takes place, in some cases, many hundreds of years after the fort’s initial construction.

A little-discussed possibility which is gaining momentum is that some of these forts may not have been forts at all. The very term “fort” is loaded and implies inherent military purpose, which remains a hypothesis with little solid evidence to its claim. Rather, they may have been monuments that were built and burned as displays of power and prestige or in some ritual event. In periods of our history where only the stones upon which we can base our suppositions remain, it is difficult to differentiate between these possibilities.

These acknowledgements highlight not only that there are outstanding questions requiring future investigation, but that each fort is different and there need not be a common explanation for them all.

The debate continues and, although the evidence sheds new light on the possible truths, we still do not know why Iron Age peoples throughout Europe set fire to stone enclosures and stoked those fires to volcanic temperatures. Rocks melt and crystallize and re-melt in volcanoes frequently and as a matter of natural process. To combine our understanding of these rock-forming materials and Earth processes as they are melted in anthropogenic conflagrations is essential to understand these curiosities of our Iron Age.

By Fabian Wadsworth, PhD student Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, and Rebecca Hearne, Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield

—

The Wincobank hillfort is in Sheffield in South Yorkshire, U.K. If the stone walls of its enclosure were deliberately burned this feature potentially extends Sheffield’s heritage of high temperature expertise – exemplified by the once-prolific steel works of the city – much farther into the region’s past than hitherto imagined.

—

Further reading

- Sanderson and coworkers documented where forts can be found in Scotland and what rock-types were used to build them. Sanderson, F. Placido, J. Tate, Scottish vitrified forts: background and potential for TL dating. Nucl. Tracks Radiation (1985)

- Youngblood and coworkers used geochemical methods to constrain the times and temperatures of the fires that produce vitrified forts. Youngblood, B. J. Fredriksson, F. Kraut, K. Fredriksson, Celtic vitrified forts: implications of a chemical-petrological study of glasses and source rocks. J. Archaeology. Sci. 5, 99–121 (1978).

- Wadsworth, Hearne and colleagues constrained how hot and how long the fires had to burn to melt the walls. B. Wadsworth et al., The feasibility of vitrifying a sandstone enclosure in the British Iron Age. J. Archaeology. Sci. Reports (2015).

- Wadsworth and coworkers find that fort walls get stronger when burned and vitrified. Wadsworth, M. Heap, D. Dingwell, Friendly fire: Engineering a fort wall in the Iron Age. J. Archaeology. Sci. (2016)

Pingback: GeoLog | Earth Science Week 2020: Earth Materials in Our Lives - an A-Z! - GeoLog

Colin

I have visited Dunskeig in Clachan on numerous occasions since I was a child. My science teacher was from the local area as well and we talked about the formation many a time. I personally think the rock was molten in smaller quantities then placed as blocks on the ramparts then fired again. Not knowing the height of the dun when in use it’s hard to say how effective it would have been . The rock it’s self is only partially verified , it would be more a kin to a rough cast on a modern house. There is also another dun directly across from Dunskeig. This can be located at the parking area just the 3entrance to Ronachon house.

JTS

It is unclear from casual reading whether the wall blocks show an alteration rind of the original rock core or a glaze of different or melded composition? Is there evidence of an additional “dry” medium such as coal, ash or asphalt, being incorporated in the walls to facilitate the production of a ‘glassy’ fusion during the wall firing?

Donald Osbourne

Has anyone considered heat created during an asteroid impact causing the vitrified rocks, there is emerging evidence of such an impact in Greenland with probable age of 12,000 – 13,000 ybp.

Bev H

See ‘The Wolf Cataclysm’ by Geoffrey Dixon

Iain

I’m here chasing that theory. I read somewhere about a cataclysmic meteor devestating Britain, but can’t remember where I read it.

Tom Robinson

Just ask an ancient gardener, how do you remove gorse from your castle walls each season ? You burn it ! Gorse burns hotter than hell and it was done year after year.

Tom Welsh

I’m glad someone has put this forward. The scientists rule out spot fires (individual bonfires) that might have spread, eg through wildfire, on the grounds no-one would carry up enough fuel for a small fire that would burn hot enough to cause the melt (though they do not explain how the fuel was carried up for the larger firings). In the 19th and 20th century fuel was carried up onto heights (and frequently on vitrified forts) for celebration fires on estates, and later for jubilees and coronations. Some of these did cause localised vitrification. If similar practices were occurring in the prehistoric, spot fires or wildfire triggered by them, might well have caused this. Granted this is not as exciting as the debate whether they were burned to strengthen the walls. I have addressed this this week in a book published on Amazon Kindle “Hilltop Bonfires – Marking Royal Events” if I am allowed to mention it here. The debate about vitrified forts needs to be more open and a lot more inclusive. For too long it has been confined to rather intellectual journals where no-one can easily comment.

Pingback: La vetrificazione dei forti dell’età del ferro in Gran Bretagna [EN] – hookii