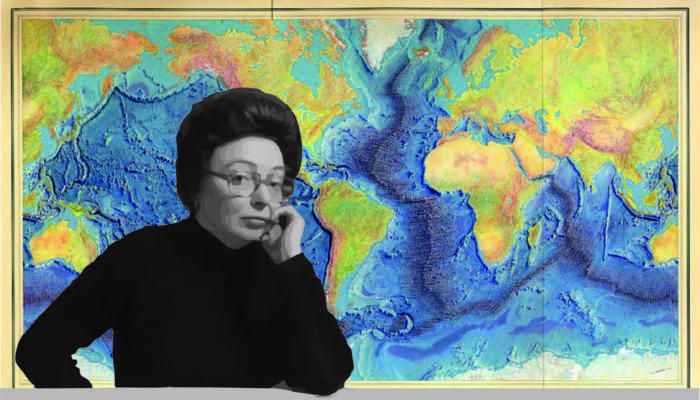

Today marks the centennial of the birth of Marie Tharp, the person responsible for creating the first map of our planet’s ocean floors. Though her work was underappreciated at the time of its publication – mainly because she faced many significant barriers due to her gender – her maps ended up being instrumental evidence in support of the theory of plate tectonics. Marie herself suggested this connection in 1952 when she identified a feature that split the Atlantic as a rift valley, but even her research partner Bruce Hezeen dismissed her idea as ‘girl-talk’.

Despite these difficulties her work is still influential, as projects such as the Seabed 2030 Project race to fill in the gaps in our seafloor understanding. Marie Tharp is an inspiring figure, not only due to her science and cartography work, but because of her dedication to her work in the face of relentless prejudice and her interdisciplinary thinking. After she plotted the map she worked with an Austrian artist, Heinrich Berann to produce the stunning images we now find so familiar. In 1999, while reflecting on her amazing career, Marie Tharp herself said:

I was so busy making maps I let them argue. I figured I’d show them a picture of where the rift valley was and where it pulled apart. There’s truth to the old clichés that a picture is worth a thousand words and that seeing is believing.

I think our maps contributed to a revolution in geological thinking, which in some ways compares to the Copernican revolution. Scientists and the general public got their first relatively realistic image of a vast part of the planet that they could never see.

Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge that went all the way around the world for 40,000 miles—that was something important. You could only do that once. You can’t find anything bigger than that, at least on this planet.

To celebrate the impact that Marie Tharp continues to have on the geosciences community, we spoke to six researchers working in the fields of ocean science, tectonics, and mapping and asked them what Marie Tharp’s work means to them personally, as well as to the future of ocean science and tectonic research.

Professor Susanne Buiter, professor of tectonics and geodynamics at RWTH Aachen University, Germany. Susanne co-organised the Marie Tharp special session at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020.

Professor Susanne Buiter, professor of tectonics and geodynamics at RWTH Aachen University, Germany. Susanne co-organised the Marie Tharp special session at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020.

“Marie Tharp’s maps of the ocean floor are so inspiring on many levels! To me they show how new data, even when only sparse, can bring tectonic understanding to an entirely new level. They also show how crucial careful interpretation of data is, through which she essentially highlighted the ocean rift system for the first time. I hope her maps keep inspiring people, encouraging us to map the seafloor in high detail and to search for understanding of the tectonic processes creating these structures.”

Gabriella Alodia, PhD candidate at Leeds University, UK. Gabriella presented her research on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020. You can read her work here.

Gabriella Alodia, PhD candidate at Leeds University, UK. Gabriella presented her research on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020. You can read her work here.

“It never ceases to fascinate me that the person behind the map of the ocean floor – my favourite map of all time – is a woman. Marie Tharp has been and will always be the reason of my continuous academic pursuit in the marine geosciences world. Her work has been a turning point, which enables us to see the world below the waters in a better way.”

Dr Dawn Wright, marine geographer, ocean scientist and chief scientist at ESRI. Dawn wrote an article about Marie Tharp’s legacy and the importance of maps that you can read here.

Dr Dawn Wright, marine geographer, ocean scientist and chief scientist at ESRI. Dawn wrote an article about Marie Tharp’s legacy and the importance of maps that you can read here.

“As a seagoing mapper of the ocean floor who started working professionally just as Marie Tharp was finally being recognized for her great scientific accomplishments, her life story is a burning, guiding light for me. In fact, her story, especially as told within the pages of Hali Felt’s book “Soundings…” provides such a good overview of the 20th-century history of oceanography that I would recommend it as required reading for all oceanography students, as well as students of cartography. In my view, Marie Tharp literally invented the field of marine cartography. And in terms of the future, given the ubiquity of ships, vehicles, robots, and their accompanying data streams, Tharp’s work continues to show us that mapping technologies need to integrate not only intuitive design but artistic beauty. This ultimately helps us to do the best science.”

Dr Lucia Perez Diaz, post-doctoral research assistant at Oxford University, UK. Lucia presented her research on the speed of plate tectonics and their driving forces at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020. Read her work here.

Dr Lucia Perez Diaz, post-doctoral research assistant at Oxford University, UK. Lucia presented her research on the speed of plate tectonics and their driving forces at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020. Read her work here.

“Marie Tharp undoubtedly changed our discipline. Her contributions played a key role in deciphering the stories told by oceans, which in turn hold the keys for studies of plate tectonics, palaeoclimate, water circulation and many others. The more I’ve learnt about her over the past few years, the more I have grown to admire her drive and motivation. She comes across to me as someone with insatiable curiosity, who through her own determination and despite the obstacles she faced (which I’m sure were more challenging than we can imagine) succeeded in building a career that she loved, and was proud of. As a woman in science, I can’t imagine a better dream to work towards.”

Dr Vicki Ferrini, senior research scientist in marine geology and geophysics at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, USA. Vicki gave a presentation on Marie Tharp’s legacy for Sharing Geoscience Online 2020 (you can read her presentation here) and presented in the special press conference: Centennial perspectives: A celebration of Marie Tharp’s legacy (watch the presentation here).

Dr Vicki Ferrini, senior research scientist in marine geology and geophysics at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, USA. Vicki gave a presentation on Marie Tharp’s legacy for Sharing Geoscience Online 2020 (you can read her presentation here) and presented in the special press conference: Centennial perspectives: A celebration of Marie Tharp’s legacy (watch the presentation here).

“Marie Tharp’s maps were building blocks for discoveries that transformed our understanding of the planet and they revealed the shape of the seafloor in ways that both scientists and the public could understand. Her ability to visualize the seafloor so clearly and correctly based on so little data is truly remarkable. Her work is an inspiring example of the importance of sharing and synthesizing data to enable new discoveries.”

Dr Anouk Beniest, research fellow at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands and EGU’s Early Career Scientist Union Representative. Anouk presented her work on offshore geological mapping at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020. Read her work here.

Dr Anouk Beniest, research fellow at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands and EGU’s Early Career Scientist Union Representative. Anouk presented her work on offshore geological mapping at Sharing Geoscience Online 2020. Read her work here.

“To me, Marie Tharp’s work means that with perseverance and willpower we can impact our scientific field and society beyond our imagination. Her work has been, and still is, instrumental to everyone who interacts with the offshore domain, whether in science, the industry or personally. Her maps show how little we knew about the ocean floor 75 years ago, how much we have achieved in understanding the offshore domain, and they will remain the solid foundation of future research in ocean sciences and plate tectonics.”

Read more about Marie Tharp’s legacy on the special Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University centennial website.

Renate de Gruyter

Woman in science shouldn‘t have to wait many years to beeing allowed on an oceanographic research vessel like the genious Marie Tharp. Woman in all science should be supported and encouraged to improve their visibility, also within their own research institutions.