This month for GeoTalk, as we approach the centennial of Marie Tharp’s birth next week, we were lucky enough to speak with the author of her biography ‘Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor‘; Hali Felt. Hali has a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Iowa and has completed residencies at MacDowell, the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, and Portland Writers in the Schools. It was during her research that she first came across Marie Tharp’s story, and ended up writing a book described by the New York Times as a biography-with-creative-indulgences that is “an eloquent testament both to Tharp’s importance and to Felt’s powers of imagination.”

Hi Hali, thank you so much for speaking with us today, Can you start by telling us a little about who Marie Tharp is and why her story is important?

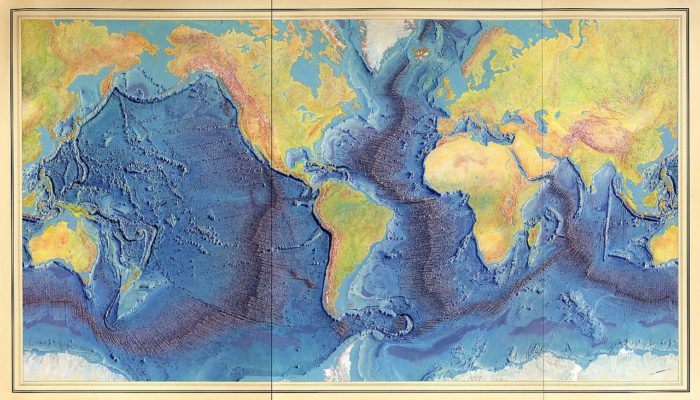

Marie Tharp is a geologist and oceanographic cartographer who created the first map to show the seven-tenths of the earth’s surface that lies below the sea; to do so she imagined the world with its oceans drained, illustrating structures that led to the paradigm-shifting theory of plate tectonics. Without her 1952 discovery of the rift valley running down the center of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (which was initially dismissed by her colleagues at Columbia University as “girl talk”), the now-famous geologists known for discovering how our planet’s plates move wouldn’t have had anything to look at. She’s also remarkable because of her commitment to creating work accessible to the public; beginning in 1967 artistic rendering of her maps of individual oceans were published in National Geographic. Her opus was the 1977 World Ocean Floor Panorama, painted by Heinrich Berann.

What inspired you to write the book, ‘Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor‘?

I first read about Marie Tharp, the subject of Soundings, in the New York Times Magazine’s end of the year The Lives They Lived issue. I was immediately fascinated by the idea of mapping the ocean floor—from the most basic idea of what Tharp’s maps looked like (I immediately looked up images of them online) to the more fanciful aspects of the story (a partnership with her working and possible romantic partner Bruce Heezen, which was portrayed in the article as rather explosive).

At the time, I was a graduate student studying creative writing, not interested in science—but I was totally in love with all of the imaginative possibilities I could see stemming from a story about a woman who mapped the ocean floor. The first question I really wanted to answer was ‘How do you understand something you can’t see?’

Six months after I first read about Tharp, I took a research trip to the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian archives to go through her and Heezen’s papers. That was when I knew I had to write a biography of Tharp—I was confronted by a vast (more than 50,000 pieces) amount of material that had never, I was told, been studied in detail by a writer or scholar. Six months after that, I had the chance to spend a day in Tharp’s house. I was one of a handful of people in the house that day, and it was overwhelming. The house was still packed with Tharp’s personal and professional belongings and we were all trying to go through and save what we could—throw it in boxes so that it would make it to the Library of Congress instead of ending up in the dumpster. Saving history.

Photo of Hali Felt (Credit: Matthew Cotter) and the cover of her book, ‘Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor.’

A few years into the project my research question changed. Instead of simply wanting to know how Marie came to map and understand the ocean floor, I wanted to trace the story of why and how she’d been overlooked by history. To answer that question, I familiarized myself not just with what scientists believe now about how the Earth’s surface was shaped—but also with the evolving beliefs scientists have held since the beginning of the 20th century. As someone who had nothing to do with science before stumbling onto Tharp, I’ve had my whole world changed; as an outsider, I’ve also developed some very different stories about the history of plate tectonics than the ones that are commonly told by today’s historians and scientists.

What is your favourite story about Marie Tharp, that you discovered whilst writing Soundings?

Marie’s work was very much shaped by the unconventional path she took to become a geologist and map maker. She had an innate love of the arts and humanities that led her to major in English, music, and philosophy before settling on geology. I believe that the interdisciplinary nature of her mind allowed her to innovate, and hope that her story inspires young women and educators to teach and become in new ways. Marie wouldn’t have chosen to experience the gender discrimination that told her the humanities were a “better fit” and forced her to work in an office rather than the field (at the time, women were banned from ocean expeditions because they were considered bad luck), but the result was that she found her calling closer to home, and mapped 70 percent of the Earth’s surface in the process.

Find Hali’s book, ‘Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor‘ here.

Interview by Hazel Gibson, EGU Communications Officer.