Why do I feel uncomfortable as the only woman in a meeting? Why do they gossip about the male postdoc who is supervising three female MSc students? Have I really been asked to give this presentation just because I am a woman? It was thanks to all the work and reading I was doing for our study about gender inequality in the geosciences that I realised it is not ok I have to ask myself these questions.

In early 2018, it was my colleague and friend Andrea who came up with the idea to conduct an online survey about how geoscientists perceive gender stereotypes and inequality in their work environment. This was initially planned as a contribution to a session at the EGU General Assembly 2018. But once we realised how much this topic resonated in our community, we decided to aim for a publication in a scientific journal. ‘We’ are five early career hydrologists: Andrea Popp, Tim van Emmerik, Sina Khatami, Wouter Knoben and myself. None of us had prior experience conducting and analysing surveys, so we had to learn on the fly how to ask unambiguous questions and give the right number of possible answers. In just one month, more than 1200 people had participated in the online survey and we worked hard over the summer to analyse the results and write a story around them.

One and a half years later – after struggling with rejections from several geoscience journals – our study was finally accepted for publication in Earth and Space Science. We are happy to be able to contribute to the current conversation on this topic, which has been receiving more attention online (such as the Nature Geosciences Editorial “Of rocks and social justice” and a blog post from the EGU Hydrological Sciences division blog by Bettina Schaefli from the University of Bern.

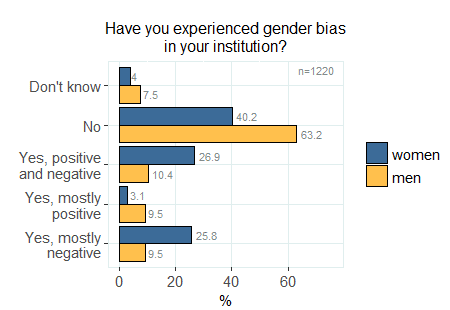

The bottom line of our study is that we have serious problems with gender bias and inequality in our scientific community, and that these problems are not generally recognised in our community. Most strikingly, more than a quarter of the female respondents reported experiences with negative gender bias at their workplace (compared to under 10% of their male colleagues; see figure below).

Experiences with bias in scientific organizations among female vs. male respondents. Credit: Popp, A. L., Lutz, S. R., Khatami, S.,van Emmerik, T., & Knoben,W. J. M. (2019).

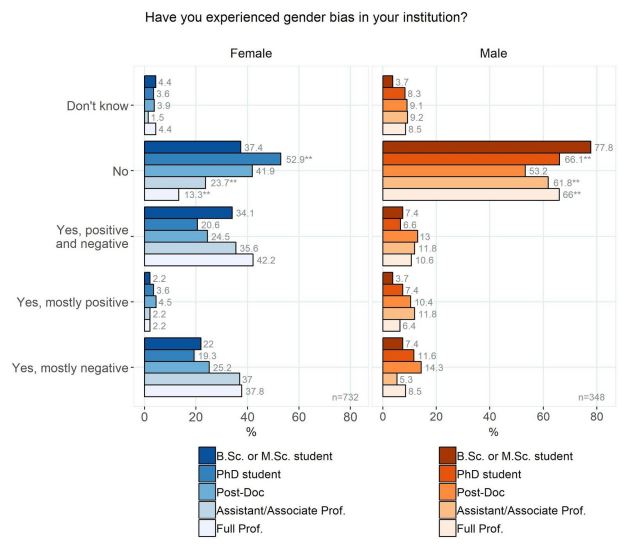

The respondents generally considered male geoscientists as more gender-biased than female geoscientists, and this became particularly obvious at the level of female professors, nearly half of whom perceive their male colleagues as gender-biased. Among the male respondents, however, it’s the postdocs who seem to feel most affected by negative gender biases. One explanation for this might be that some male postdocs expect disadvantages from policies that support early-career female scientists who might compete with them for the same positions.

Experience with gender bias in institutions by female and male respondents in each career level. Asterisks indicate statistically significant gender differences in each career level per category according to Fisher’s exact tests. Credit: Popp, A. L., Lutz, S. R., Khatami, S.,van Emmerik, T., & Knoben,W. J. M. (2019).

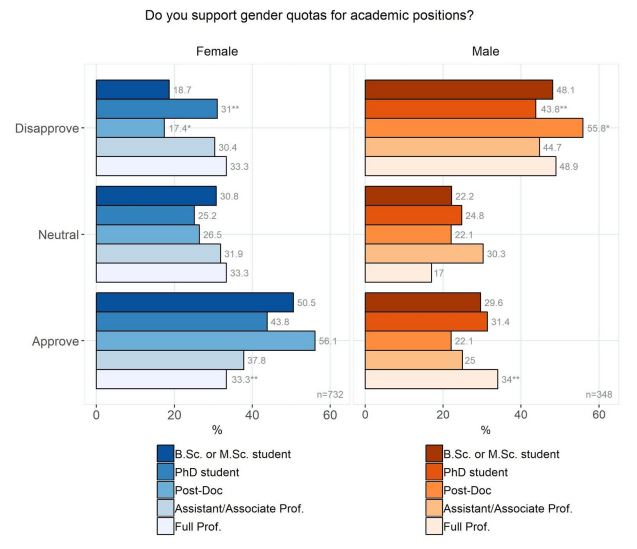

A crucial problem with a gender-imbalanced faculty, especially at higher career levels, is the lack of female role models at the workplace and conferences. Most of the female participants (84%) stated that role models are important to them and about a third of them prefer same-gender role models. But how can we make sure to have more female role models in academia? One could argue that gender quotas for academic positions would be a good way to attract and employ more women. However, our survey shows that gender quotas are a controversial issue, even among female respondents, with a quarter of them being rather critical of such quotas.

Approval vs. disapproval of gender quotas for academic positions among female and male respondents in each career level. Asterisks indicate statistically significant gender differences in each career level per category according to χ2-tests. Credit: Popp, A. L., Lutz, S. R., Khatami, S.,van Emmerik, T., & Knoben,W. J. M. (2019).

The key implication of our study is that those in leading positions – whose actions might have the largest impact – are the least affected by gender inequality in their job and might thus not see a good reason for taking a stand for more diversity and equality. In my own experience, I have had discussions with male senior scientists who are indeed willing to improve the current imbalance, but also believe that by inviting more women for job interviews or waiting for female students to move up the career ladder, the number of female senior scientists will gradually increase and the problem will finally be resolved.

In our paper, we argue that we as a community need to do so much more than this. We stress that, while the science community should certainly make an extra effort to look for qualified women when hiring new staff or awarding prizes, it is at least as important to challenge and improve the way we do research on a daily basis, interact and collaborate with each other and acknowledge our colleagues’ work.

Based on recent must-read literature (for example, Holmes et al., 2015) and personal discussions, we suggest several strategies in our paper to promote gender equality, among which are mandatory gender bias training, a transparent and standardised selection of job candidates and research grant awardees, more gender balance on the decision-making level of research institutions and scientific organisations such as EGU, and more flexible and family-friendly working conditions to support parents and informal caregivers.

And, above all, we should promote an open and continuous discussion about these matters, together with male colleagues of all career levels. Having such discussions can raise more awareness of the negative impact of exclusionary climates that exist in some institutions and scientific communities. These kind of environments can be harmful and daunting not only to female scientists, but also to ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ community, and everyone else who might not fit in with the ‘old white boys club’ culture. By having productive conversations on inappropriate and sexist comments, the feeling of being patronised or even silenced in discussions, or the pressure of having to work twice as hard to be recognised, we can work towards addressing these issues collectively.

So if you care about good science and happy scientists, please try to bring up this topic during meetings or personal conversations, and – if you are a woman scientist – find allies among your male colleagues who fight alongside you. Why should we all make an effort? Because we need a more gender-balanced and diverse workforce that ensures diverse perspectives, a more enjoyable work life and simply better science!

By Stefanie Lutz, Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research, Germany

References